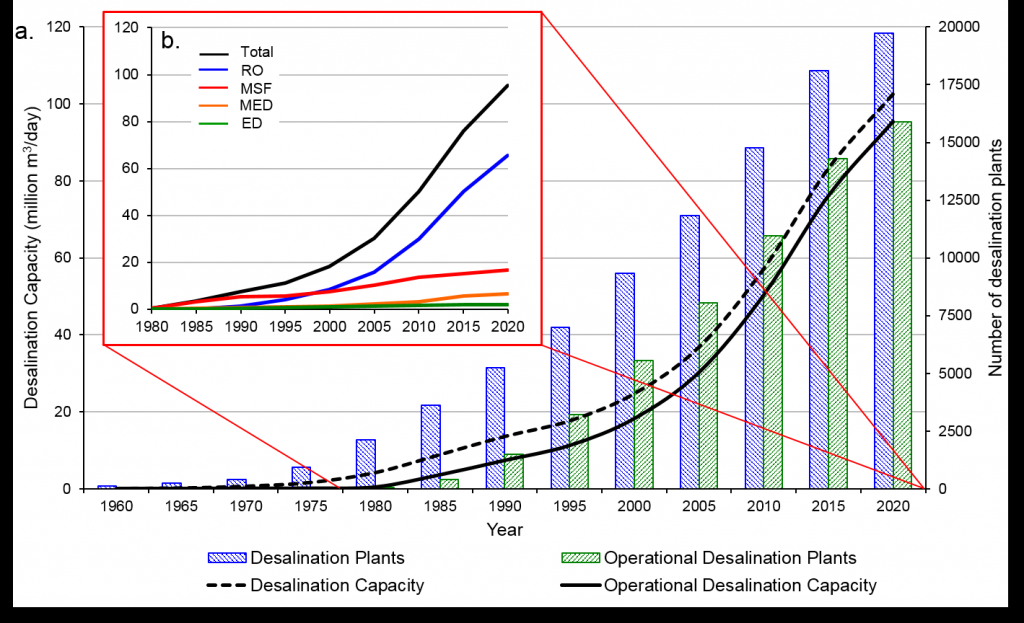

Have you ever wondered about the possible effects and impact of desalinating large amounts of ocean water? It seems that some United Nations University (UNU) researchers have asked and are beginning to answer that question. The following table illustrates the rise in desalination plants and processes,

Today 15,906 operational desalination plants are found in 177 countries. Almost half of the global desalination capacity is located in the Middle East and North Africa region (48 percent), with Saudi Arabia (15.5 percent), the United Arab Emirates (10.1 percent) and Kuwait (3.7 percent) being both the major producers in the region and globally. Credit: UNU-INWEH [downloaded from http://inweh.unu.edu/un-warns-of-rising-levels-of-toxic-brine-as-desalination-plants-meet-growing-water-needs/]

A January 14, 2019 news item on phys.org highlights the study on desalination from the UNU,

The fast-rising number of desalination plants worldwide—now almost 16,000, with capacity concentrated in the Middle East and North Africa—quench a growing thirst for freshwater but create a salty dilemma as well: how to deal with all the chemical-laden leftover brine.

In a UN-backed paper, experts estimate the freshwater output capacity of desalination plants at 95 million cubic meters per day—equal to almost half the average flow over Niagara Falls.

For every litre of freshwater output, however, desalination plants produce on average 1.5 litres of brine (though values vary dramatically, depending on the feedwater salinity and desalination technology used, and local conditions). Globally, plants now discharge 142 million cubic meters of hypersaline brine every day (a 50% increase on previous assessments).That’s enough in a year (51.8 billion cubic meters) to cover Florida under 30.5 cm (1 foot) of brine.

The authors, from UN University’s Canadian-based Institute for Water, Environment and Health [at McMaster University], Wageningen University, The Netherlands, and the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Republic of Korea, analyzed a newly-updated dataset—the most complete ever compiled—to revise the world’s badly outdated statistics on desalination plants.

And they call for improved brine management strategies to meet a fast-growing challenge, noting predictions of a dramatic rise in the number of desalination plants, and hence the volume of brine produced, worldwide.

A January 14, 2017 UNU press release, which originated the news item, details the findings,

The paper found that 55% of global brine is produced in just four countries: Saudi Arabia (22%), UAE (20.2%), Kuwait (6.6%) and Qatar (5.8%). Middle Eastern plants, which largely operate using seawater and thermal desalination technologies, typically produce four times as much brine per cubic meter of clean water as plants where river water membrane processes dominate, such as in the US.

The paper says brine disposal methods are largely dictated by geography but traditionally include direct discharge into oceans, surface water or sewers, deep well injection and brine evaporation ponds.

Desalination plants near the ocean (almost 80% of brine is produced within 10km of a coastline) most often discharge untreated waste brine directly back into the marine environment.

The authors cite major risks to ocean life and marine ecosystems posed by brine greatly raising the salinity of the receiving seawater, and by polluting the oceans with toxic chemicals used as anti-scalants and anti-foulants in the desalination process (copper and chlorine are of major concern).

“Brine underflows deplete dissolved oxygen in the receiving waters,” says lead author Edward Jones, who worked at UNU-INWEH, and is now at Wageningen University, The Netherlands. “High salinity and reduced dissolved oxygen levels can have profound impacts on benthic organisms, which can translate into ecological effects observable throughout the food chain.”

Meanwhile, the paper highlights economic opportunities to use brine in aquaculture, to irrigate salt tolerant species, to generate electricity, and by recovering the salt and metals contained in brine — including magnesium, gypsum, sodium chloride, calcium, potassium, chlorine, bromine and lithium.

With better technology, a large number of metals and salts in desalination plant effluent could be mined. These include sodium, magnesium, calcium, potassium, bromine, boron, strontium, lithium, rubidium and uranium, all used by industry, in products, and in agriculture. The needed technologies are immature, however; recovery of these resources is economically uncompetitive today.

“There is a need to translate such research and convert an environmental problem into an economic opportunity,” says author Dr. Manzoor Qadir, Assistant Director of UNU-INWEH. “This is particularly important in countries producing large volumes of brine with relatively low efficiencies, such as Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait and Qatar.”

“Using saline drainage water offers potential commercial, social and environmental gains. Reject brine has been used for aquaculture, with increases in fish biomass of 300% achieved. It has also been successfully used to cultivate the dietary supplement Spirulina, and to irrigate forage shrubs and crops (although this latter use can cause progressive land salinization).”

“Around 1.5 to 2 billion people currently live in areas of physical water scarcity, where water resources are insufficient to meet water demands, at least during part of the year. Around half a billion people experience water scarcity year round,” says Dr. Vladimir Smakhtin, a co-author of the paper and the Director of UNU-INWEH, whose institute is actively pursuing research related to a variety of unconventional water sources.

“There is an urgent need to make desalination technologies more affordable and extend them to low-income and lower-middle income countries. At the same time, though, we have to address potentially severe downsides of desalination — the harm of brine and chemical pollution to the marine environment and human health.”

“The good news is that efforts have been made in recent years and, with continuing technology refinement and improving economic affordability, we see a positive and promising outlook.”

¹The authors use the term “brine” to refer to all concentrate discharged from desalination plants, as the vast majority of concentrate (>95%) originates from seawater and highly brackish groundwater sources.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

The state of desalination and brine production: A global outlook by Edward Jones, Manzoor Qadir, Michelle T.H.van Vliet, Vladimir Smakhtin, Seong-mu Kang. Science of The Total Environment Volume 657, 20 March 2019, Pages 1343-1356 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.076 Available online 7 December 2018

Surprisingly (to me anyway), this paper is behind a paywall.