This is a roundup post of four items to cross my path this morning (Dec. 17, 2015), all of them concerned with wearable technology.

The first, a Dec. 16, 2015 news item on phys.org, is a fluffy little piece concerning the imminent arrival of a new generation of wearable technology,

It’s not every day that there’s a news story about socks. But in November [2015], a pair won the Best New Wearable Technology Device Award at a Silicon Valley conference. The smart socks, which track foot landings and cadence, are at the forefront of a new generation of wearable electronics, according to an article in Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society [ACS].

That news item was originated by a Dec. 16, 2015 ACS news release on EurekAlert which adds this,

Marc S. Reisch, a senior correspondent at C&EN, notes that stiff wristbands like the popular FitBit that measure heart rate and the number of steps people take have become common. But the long-touted technology needed to create more flexible monitoring devices has finally reached the market. Developers have successfully figured out how to incorporate stretchable wiring and conductive inks in clothing fabric, program them to transmit data wirelessly and withstand washing.

In addition to smart socks, fitness shirts and shoe insoles are on the market already or are nearly there. Although athletes are among the first to gain from the technology, the less fitness-oriented among us could also benefit. One fabric concept product — designed not for covering humans but a car steering-wheel — could sense driver alertness and make roads safer.

Reisch’s Dec. 7, 2015 article (C&EN vol. 93, issue 48, pp. 28-90) provides more detailed information and market information such as this,

Materials suppliers, component makers, and apparel developers gathered at a printed-electronics conference in Santa Clara, Calif., within a short drive of tech giants such as Google and Apple, to compare notes on embedding electronics into the routines of daily life. A notable theme was the effort to stealthily [emphasis mine] place sensors on exercise shirts, socks, and shoe soles so that athletes and fitness buffs can wirelessly track their workouts and doctors can monitor the health of their patients.

“Wearable technology is becoming more wearable,” said Raghu Das, chief executive officer of IDTechEx [emphasis mine], the consulting firm that organized the conference. By that he meant the trend is toward thinner and more flexible devices that include not just wrist-worn fitness bands but also textiles printed with stretchable wiring and electronic sensors, thanks to advances in conductive inks.

Interesting use of the word ‘stealthy’, which often suggests something sneaky as opposed to merely secretive. I imagine what’s being suggested is that the technology will not impose itself on the user (i.e., you won’t have to learn how to use it as you did with phones and computers).

Leading into my second item, IDC (International Data Corporation), not to be confused with IDTechEx, is mentioned in a Dec. 17, 2015 news item about wearable technology markets on phys.org,

The global market for wearable technology is seeing a surge, led by watches, smart clothing and other connected gadgets, a research report said Thursday [Dec. 16, 2015].

IDC said its forecast showed the worldwide wearable device market will reach a total of 111.1 million units in 2016, up 44.4 percent from this year.

By 2019, IDC sees some 214.6 million units, or a growth rate averaging 28 percent.

A Dec. 17, 2015 IDC press release, which originated the news item, provides more details about the market forecast,

“The most common type of wearables today are fairly basic, like fitness trackers, but over the next few years we expect a proliferation of form factors and device types,” said Jitesh Ubrani , Senior Research Analyst for IDC Mobile Device Trackers. “Smarter clothing, eyewear, and even hearables (ear-worn devices) are all in their early stages of mass adoption. Though at present these may not be significantly smarter than their analog counterparts, the next generation of wearables are on track to offer vastly improved experiences and perhaps even augment human abilities.”

One of the most popular types of wearables will be smartwatches, reaching a total of 34.3 million units shipped in 2016, up from the 21.3 million units expected to ship in 2015. By 2019, the final year of the forecast, total shipments will reach 88.3 million units, resulting in a five-year CAGR of 42.8%.

“In a short amount of time, smartwatches have evolved from being extensions of the smartphone to wearable computers capable of communications, notifications, applications, and numerous other functionalities,” noted Ramon Llamas , Research Manager for IDC’s Wearables team. “The smartwatch we have today will look nothing like the smartwatch we will see in the future. Cellular connectivity, health sensors, not to mention the explosive third-party application market all stand to change the game and will raise both the appeal and value of the market going forward.

“Smartwatch platforms will lead the evolution,” added Llamas. “As the brains of the smartwatch, platforms manage all the tasks and processes, not the least of which are interacting with the user, running all of the applications, and connecting with the smartphone. Once that third element is replaced with cellular connectivity, the first two elements will take on greater roles to make sense of all the data and connections.”

Top Five Smartwatch Platform Highlights

Apple’s watchOS will lead the smartwatch market throughout our forecast, with a loyal fanbase of Apple product owners and a rapidly growing application selection, including both native apps and Watch-designed apps. Very quickly, watchOS has become the measuring stick against which other smartwatches and platforms are compared. While there is much room for improvement and additional features, there is enough momentum to keep it ahead of the rest of the market.

Android/Android Wear will be a distant second behind watchOS even as its vendor list grows to include technology companies (ASUS, Huawei, LG, Motorola, and Sony) and traditional watchmakers (Fossil and Tag Heuer). The user experience on Android Wear devices has been largely the same from one device to the next, leaving little room for OEMs to develop further and users left to select solely on price and smartwatch design.

Smartwatch pioneer Pebble will cede market share to AndroidWear and watchOS but will not disappear altogether. Its simple user interface and devices make for an easy-to-understand use case, and its price point relative to other platforms makes Pebble one of the most affordable smartwatches on the market.

Samsung’s Tizen stands to be the dark horse of the smartwatch market and poses a threat to Android Wear, including compatibility with most flagship Android smartphones and an application selection rivaling Android Wear. Moreover, with Samsung, Tizen has benefited from technology developments including a QWERTY keyboard on a smartwatch screen, cellular connectivity, and new user interfaces. It’s a combination that helps Tizen stand out, but not enough to keep up with AndroidWear and watchOS.

There will be a small, but nonetheless significant market for smart wristwear running on a Real-Time Operating System (RTOS), which is capable of running third-party applications, but not on any of these listed platforms. These tend to be proprietary operating systems and OEMs will use them when they want to champion their own devices. These will help within specific markets or devices, but will not overtake the majority of the market.

The company has provided a table with five-year CAGR (compound annual growth rate) growth estimates, which can be found with the Dec. 17, 2015 IDC press release.

Disclaimer: I am not endorsing IDC’s claims regarding the market for wearable technology.

For the third and fourth items, it’s back to the science. A Dec. 17, 2015 news item on Nanowerk, describes, in general terms, some recent wearable technology research at the University of Manchester (UK), Note: A link has been removed),

Cheap, flexible, wireless graphene communication devices such as mobile phones and healthcare monitors can be directly printed into clothing and even skin, University of Manchester academics have demonstrated.

In a breakthrough paper in Scientific Reports (“Highly Flexible and Conductive Printed Graphene for Wireless Wearable Communications Applications”), the researchers show how graphene could be crucial to wearable electronic applications because it is highly-conductive and ultra-flexible.

The research could pave the way for smart, battery-free healthcare and fitness monitoring, phones, internet-ready devices and chargers to be incorporated into clothing and ‘smart skin’ applications – printed graphene sensors integrated with other 2D materials stuck onto a patient’s skin to monitor temperature, strain and moisture levels.

Detail is provided in a Dec. 17, 2015 University of Manchester press release, which originated the news item, (Note: Links have been removed),

Examples of communication devices include:

• In a hospital, a patient wears a printed graphene RFID tag on his or her arm. The tag, integrated with other 2D materials, can sense the patient’s body temperature and heartbeat and sends them back to the reader. The medical staff can monitor the patient’s conditions wirelessly, greatly simplifying the patient’s care.

• In a care home, battery-free printed graphene sensors can be printed on elderly peoples’ clothes. These sensors could detect and collect elderly people’s health conditions and send them back to the monitoring access points when they are interrogated, enabling remote healthcare and improving quality of life.

Existing materials used in wearable devices are either too expensive, such as silver nanoparticles, or not adequately conductive to have an effect, such as conductive polymers.

Graphene, the world’s thinnest, strongest and most conductive material, is perfect for the wearables market because of its broad range of superlative qualities. Graphene conductive ink can be cheaply mass produced and printed onto various materials, including clothing and paper.

“Sir Kostya Novoselov

To see evidence that cheap, scalable wearable communication devices are on the horizon is excellent news for graphene commercial applications.

Sir Kostya Novoselov (tweet)„

The researchers, led by Dr Zhirun Hu, printed graphene to construct transmission lines and antennas and experimented with these in communication devices, such as mobile and Wifi connectivity.

Using a mannequin, they attached graphene-enabled antennas on each arm. The devices were able to ‘talk’ to each other, effectively creating an on-body communications system.

The results proved that graphene enabled components have the required quality and functionality for wireless wearable devices.

Dr Hu, from the School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, said: “This is a significant step forward – we can expect to see a truly all graphene enabled wireless wearable communications system in the near future.

“The potential applications for this research are huge – whether it be for health monitoring, mobile communications or applications attached to skin for monitoring or messaging.

“This work demonstrates that this revolutionary scientific material is bringing a real change into our daily lives.”

Co-author Sir Kostya Novoselov, who with his colleague Sir Andre Geim first isolated graphene at the University in 2004, added: “Research into graphene has thrown up significant potential applications, but to see evidence that cheap, scalable wearable communication devices are on the horizon is excellent news for graphene commercial applications.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Highly Flexible and Conductive Printed Graphene for Wireless Wearable Communications Applications by Xianjun Huang, Ting Leng, Mengjian Zhu, Xiao Zhang, JiaCing Chen, KuoHsin Chang, Mohammed Aqeeli, Andre K. Geim, Kostya S. Novoselov, & Zhirun Hu. Scientific Reports 5, Article number: 18298 (2015) doi:10.1038/srep18298 Published online: 17 December 2015

This is an open access paper.

The next and final item concerns supercapacitors for wearable tech, which makes it slightly different from the other items and is why, despite the date, this is the final item. The research comes from Case Western Research University (CWRU; US) according to a Dec. 16, 2015 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

Wearable power sources for wearable electronics are limited by the size of garments.

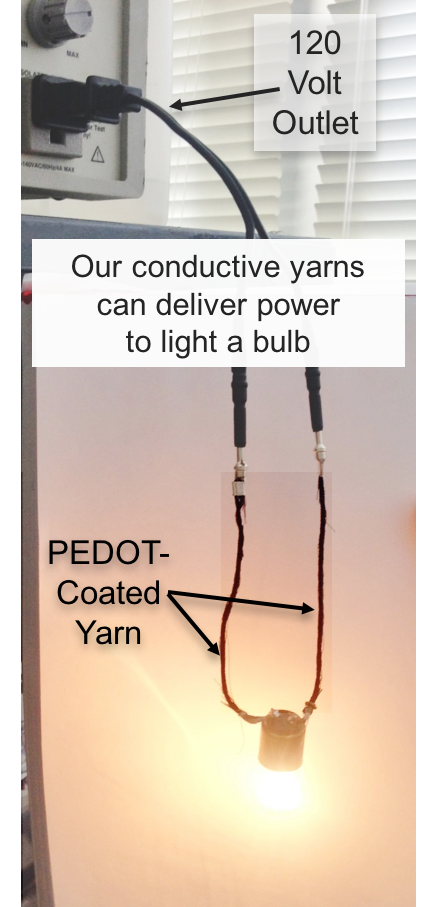

With that in mind, researchers at Case Western Reserve University have developed flexible wire-shaped microsupercapacitors that can be woven into a jacket, shirt or dress (Energy Storage Materials, “Flexible and wearable wire-shaped microsupercapacitors based on highly aligned titania and carbon nanotubes”).

A Dec. 16, 2015 CWRU news release (on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail about a device that would make wearable tech more wearable (after all, you don’t want to recharge your clothes the same way you do your phone and other mobile devices),

By their design or by connecting the capacitors in series or parallel, the devices can be tailored to match the charge storage and delivery needs of electronics donned.

While there’s been progress in development of those electronics–body cameras, smart glasses, sensors that monitor health, activity trackers and more–one challenge remaining is providing less obtrusive and cumbersome power sources.

“The area of clothing is fixed, so to generate the power density needed in a small area, we grew radially-aligned titanium oxide nanotubes on a titanium wire used as the main electrode,” said Liming Dai, the Kent Hale Smith Professor of Macromolecular Science and Engineering. “By increasing the surface area of the electrode, you increase the capacitance.”

Dai and Tao Chen, a postdoctoral fellow in molecular science and engineering at Case Western Reserve, published their research on the microsupercapacitor in the journal Energy Storage Materials this week. The study builds on earlier carbon-based supercapacitors.

A capacitor is cousin to the battery, but offers the advantage of charging and releasing energy much faster.

How it works

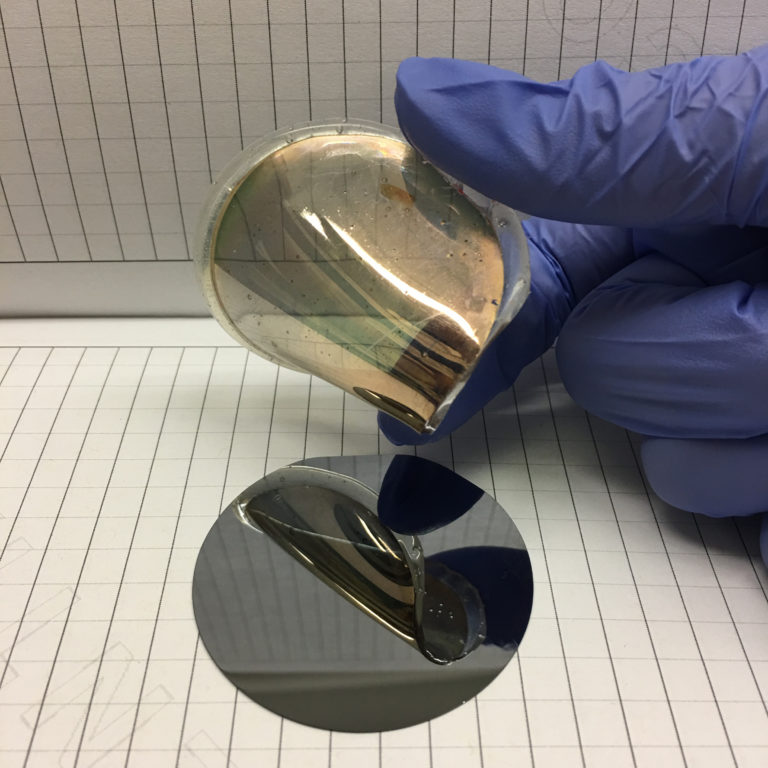

In this new supercapacitor, the modified titanium wire is coated with a solid electrolyte made of polyvinyl alcohol and phosphoric acid. The wire is then wrapped with either yarn or a sheet made of aligned carbon nanotubes, which serves as the second electrode. The titanium oxide nanotubes, which are semiconducting, separate the two active portions of the electrodes, preventing a short circuit.

In testing, capacitance–the capability to store charge–increased from 0.57 to 0.9 to 1.04 milliFarads per micrometer as the strands of carbon nanotube yarn were increased from 1 to 2 to 3.

When wrapped with a sheet of carbon nanotubes, which increases the effective area of electrode, the microsupercapactitor stored 1.84 milliFarads per micrometer. Energy density was 0.16 x 10-3 milliwatt-hours per cubic centimeter and power density .01 milliwatt per cubic centimeter.

Whether wrapped with yarn or a sheet, the microsupercapacitor retained at least 80 percent of its capacitance after 1,000 charge-discharge cycles. To match various specific power needs of wearable devices, the wire-shaped capacitors can be connected in series or parallel to raise voltage or current, the researchers say.

When bent up to 180 degrees hundreds of times, the capacitors showed no loss of performance. Those wrapped in sheets showed more mechanical strength.

“They’re very flexible, so they can be integrated into fabric or textile materials,” Dai said. “They can be a wearable, flexible power source for wearable electronics and also for self-powered biosensors or other biomedical devices, particularly for applications inside the body.” [emphasis mine]

Dai ‘s lab is in the process of weaving the wire-like capacitors into fabric and integrating them with a wearable device.

So one day we may be carrying supercapacitors in our bodies? I’m not sure how I feel about that goal. In any event, here’s a link and a citation for the paper,

Flexible and wearable wire-shaped microsupercapacitors based on highly aligned titania and carbon nanotubes by Tao Chen, Liming Dai. Energy Storage Materials Volume 2, January 2016, Pages 21–26 doi:10.1016/j.ensm.2015.11.004

This paper appears to be open access.