An October 21, 2021 news item on phys.org features a quote about nothingness and symmetry (Note: A link has been removed),

In research that could inform future high-performance nanomaterials, a University of Michigan-led team has uncovered for the first time how mollusks build ultradurable structures with a level of symmetry that outstrips everything else in the natural world, with the exception of individual atoms.

“We humans, with all our access to technology, can’t make something with a nanoscale architecture as intricate as a pearl,” said Robert Hovden, U-M assistant professor of materials science and engineering and an author on the paper. “So we can learn a lot by studying how pearls go from disordered nothingness to this remarkably symmetrical structure.” [emphasis mine]

The analysis was done in collaboration with researchers at the Australian National University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Western Norway University [of Applied Sciences] and Cornell University.

…

An October 21, 2021 University of Michigan news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, reveals a surprise,

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [PNAS], the study found that a pearl’s symmetry becomes more and more precise as it builds, answering centuries-old questions about how the disorder at its center becomes a sort of perfection.

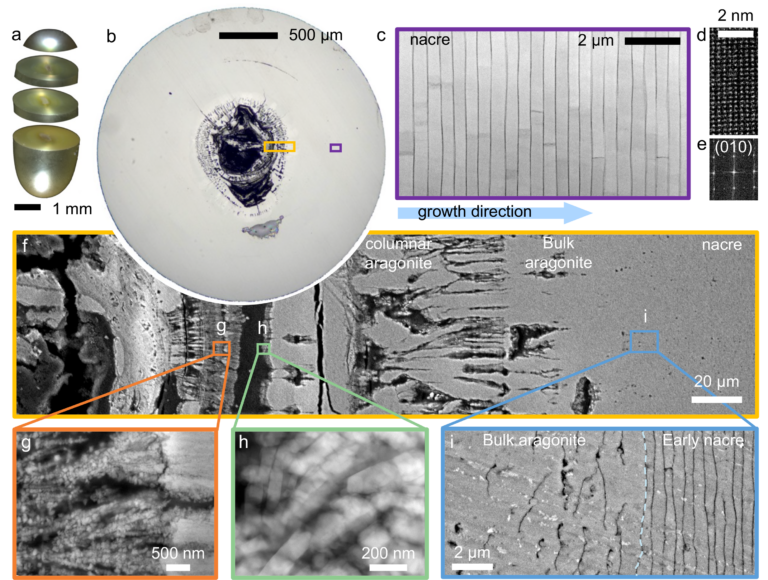

Layers of nacre, the iridescent and extremely durable organic-inorganic composite that also makes up the shells of oysters and other mollusks, build on a shard of aragonite that surrounds an organic center. The layers, which make up more than 90% of a pearl’s volume, become progressively thinner and more closely matched as they build outward from the center.

Perhaps the most surprising finding is that mollusks maintain the symmetry of their pearls by adjusting the thickness of each layer of nacre. If one layer is thicker, the next tends to be thinner, and vice versa. The pearl pictured in the study contains 2,615 finely matched layers of nacre, deposited over 548 days.

“These thin, smooth layers of nacre look a little like bed sheets, with organic matter in between,” Hovden said. “There’s interaction between each layer, and we hypothesize that that interaction is what enables the system to correct as it goes along.”

The team also uncovered details about how the interaction between layers works. A mathematical analysis of the pearl’s layers show that they follow a phenomenon known as “1/f noise,” where a series of events that seem to be random are connected, with each new event influenced by the one before it. 1/f noise has been shown to govern a wide variety of natural and human-made processes including seismic activity, economic markets, electricity, physics and even classical music.

“When you roll dice, for example, every roll is completely independent and disconnected from every other roll. But 1/f noise is different in that each event is linked,” Hovden said. “We can’t predict it, but we can see a structure in the chaos. And within that structure are complex mechanisms that enable a pearl’s thousands of layers of nacre to coalesce toward order and precision.”

The team found that pearls lack true long-range order—the kind of carefully planned symmetry that keeps the hundreds of layers in brick buildings consistent. Instead, pearls exhibit medium-range order, maintaining symmetry for around 20 layers at a time. This is enough to maintain consistency and durability over the thousands of layers that make up a pearl.

The team gathered their observations by studying Akoya “keshi” pearls, produced by the Pinctada imbricata fucata oyster near the Eastern shoreline of Australia. They selected these particular pearls, which measure around 50 millimeters in diameter, because they form naturally, as opposed to bead-cultured pearls, which have an artificial center. Each pearl was cut with a diamond wire saw into sections measuring three to five millimeters in diameter, then polished and examined under an electron microscope.

Hovden says the study’s findings could help inform next-generation materials with precisely layered nanoscale architecture.

“When we build something like a brick building, we can build in periodicity through careful planning and measuring and templating,” he said. “Mollusks can achieve similar results on the nanoscale by using a different strategy. So we have a lot to learn from them, and that knowledge could help us make stronger, lighter materials in the future.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

The mesoscale order of nacreous pearls by Jiseok Gim, Alden Koch, Laura M. Otter, Benjamin H. Savitzky, Sveinung Erland, Lara A. Estroff, Dorrit E. Jacob, and Robert Hovden. PNAS vol. 118 no. 42 e2107477118 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2107477118 Published in issue October 19, 2021 Published online October 18, 2021

This paper appears to be open access.