I don’t understand why anyone would publicize science work featuring soundscapes without including an audio file. However, no one from Princeton University (US) phoned and asked for my advice :).

On the plus side, my whale story does have a sample audio file. However, I’m not sure if I can figure out how to embed it here.

Princeton and monitoring forests

In addition to a professor from Princeton University, there’s the founder of an environmental news organization and someone who’s both a professor at the University of Queensland (Australia) and affiliated with the Nature Conservancy making this of the more unusual collaborations I’ve seen.

Moving on to the news, a January 4, 2019 Princeton University news release (also on EurekAlert but published on Jan. 3, 2019) by B. Rose Kelly announces research into monitoring forests,

Recordings of the sounds in tropical forests could unlock secrets about biodiversity and aid conservation efforts around the world, according to a perspective paper published in Science.

Compared to on-the-ground fieldwork, bioacoustics –recording entire soundscapes, including animal and human activity — is relatively inexpensive and produces powerful conservation insights. The result is troves of ecological data in a short amount of time.

Because these enormous datasets require robust computational power, the researchers argue that a global organization should be created to host an acoustic platform that produces on-the-fly analysis. Not only could the data be used for academic research, but it could also monitor conservation policies and strategies employed by companies around the world.

“Nongovernmental organizations and the conservation community need to be able to truly evaluate the effectiveness of conservation interventions. It’s in the interest of certification bodies to harness the developments in bioacoustics for better enforcement and effective measurements,” said Zuzana Burivalova, a postdoctoral research fellow in Professor David Wilcove’s lab at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

“Beyond measuring the effectiveness of conservation projects and monitoring compliance with forest protection commitments, networked bioacoustic monitoring systems could also generate a wealth of data for the scientific community,” said co-author Rhett Butler of the environmental news outlet Mongabay.

Burivalova and Butler co-authored the paper with Edward Game, who is based at the Nature Conservancy and the University of Queensland.

The researchers explain that while satellite imagery can be used to measure deforestation, it often fails to detect other subtle ecological degradations like overhunting, fires, or invasion by exotic species. Another common measure of biodiversity is field surveys, but those are often expensive, time consuming and cover limited ground.

Depending on the vegetation of the area and the animals living there, bioacoustics can record animal sounds and songs from several hundred meters away. Devices can be programmed to record at specific times or continuously if there is solar polar or a cellular network signal. They can also record a range of taxonomic groups including birds, mammals, insects, and amphibians. To date, several multiyear recordings have already been completed.

Bioacoustics can help effectively enforce policy efforts as well. Many companies are engaged in zero-deforestation efforts, which means they are legally obligated to produce goods without clearing large forests. Bioacoustics can quickly and cheaply determine how much forest has been left standing.

“Companies are adopting zero deforestation commitments, but these policies do not always translate to protecting biodiversity due to hunting, habitat degradation, and sub-canopy fires. Bioacoustic monitoring could be used to augment satellites and other systems to monitor compliance with these commitments, support real-time action against prohibited activities like illegal logging and poaching, and potentially document habitat and species recovery,” Butler said.

Further, these recordings can be used to measure climate change effects. While the sounds might not be able to assess slow, gradual changes, they could help determine the influence of abrupt, quick differences to land caused by manufacturing or hunting, for example.

Burivalova and Game have worked together previously as you can see in a July 24, 2017 article by Justine E. Hausheer for a nature.org blog ‘Cool Green Science’ (Note: Links have been removed),

Morning in Musiamunat village. Across the river and up a steep mountainside, birds-of-paradise call raucously through the rainforest canopy, adding their calls to the nearly deafening insect chorus. Less than a kilometer away, small birds flit through a grove of banana trees, taro and pumpkin vines winding across the rough clearing. Here too, the cicadas howl.

To the ear, both garden and forest are awash with noise. But hidden within this dawn chorus are clues to the forest’s health.

New acoustic research from Nature Conservancy scientists indicates that forest fragmentation drives distinct changes in the dawn and dusk choruses of forests in Papua New Guinea. And this innovative method can help evaluate the conservation benefits of land-use planning efforts with local communities, reducing the cost of biodiversity monitoring in the rugged tropics.

…

“It’s one thing for a community to say that they cut fewer trees, or restricted hunting, or set aside a protected area, but it’s very difficult for small groups to demonstrate the effectiveness of those efforts,” says Eddie Game, The Nature Conservancy’s lead scientist for the Asia-Pacific region.

Aside from the ever-present logging and oil palm, another threat to PNG’s forests is subsistence agriculture, which feeds a majority of the population. In the late 1990s, The Nature Conservancy worked with 11 communities in the Adelbert Mountains to create land-use plans, dividing each community’s lands into different zones for hunting, gardening, extracting forest products, village development, and conservation. The goal was to limit degradation to specific areas of the forest, while keeping the rest intact.

But both communities and conservationists needed a way to evaluate their efforts, before the national government considered expanding the program beyond Madang province. So in July 2015, Game and two other scientists, Zuzana Burivalova and Timothy Boucher, spent two weeks gathering data in the Adelbert Mountains, a rugged lowland mountain range in Papua New Guinea’s Madang province.

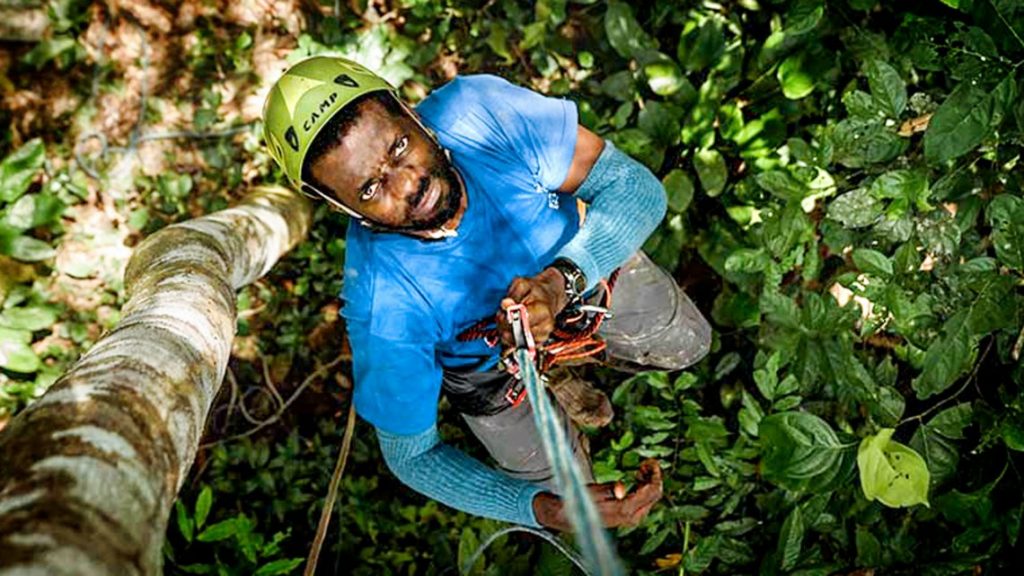

Working with conservation rangers from Musiamunat, Yavera, and Iwarame communities, the research team tested an innovative method — acoustic sampling — to measure biodiversity across the community forests. Game and his team used small acoustic recorders placed throughout the forest to record 24-hours of sound from locations in each of the different land zones.

Soundscapes from healthy, biodiverse forests are more complex, so the scientists hoped that these recordings would show if parts of the community forests, like the conservation zones, were more biodiverse than others. “Acoustic recordings won’t pick up every species, but we don’t need that level of detail to know if a forest is healthy,” explains Boucher, a conservation geographer with the Conservancy.

…

Here’s a link to and a citation for the latest work from Burivalova and Game,

The sound of a tropical forest by Zuzana Burivalova, Edward T. Game, Rhett A. Butler. Science 04 Jan 2019: Vol. 363, Issue 6422, pp. 28-29 DOI: 10.1126/science.aav1902

This paper is behind a paywall. You can find out more about Mongabay and Rhett Butler in its Wikipedia entry.

***ETA July 18, 2019: Cara Cannon Byington, Associate Director, Science Communications for the Nature Conservancy emailed to say that a January 3, 2019 posting on the conservancy’s Cool Green Science Blog features audio files from the research published in ‘The sound of a tropical forest. Scroll down about 75% of the way for the audio.***

Whale songs

Whales share songs when they meet and a January 8, 2019 Wildlife Conservation Society news release (also on EurekAlert) describes how that sharing takes place,

Singing humpback whales from different ocean basins seem to be picking up musical ideas from afar, and incorporating these new phrases and themes into the latest song, according to a newly published study in Royal Society Open Science that’s helping scientists better understand how whales learn and change their musical compositions.

The new research shows that two humpback whale populations in different ocean basins (the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans) in the Southern Hemisphere sing similar song types, but the amount of similarity differs across years. This suggests that males from these two populations come into contact at some point in the year to hear and learn songs from each other.

The study titled “Culturally transmitted song exchange between humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the southeast Atlantic and southwest Indian Ocean basins” appears in the latest edition of the Royal Society Open Science journal. The authors are: Melinda L. Rekdahl, Carissa D. King, Tim Collins, and Howard Rosenbaum of WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society); Ellen C. Garland of the University of St. Andrews; Gabriella A. Carvajal of WCS and Stony Brook University; and Yvette Razafindrakoto of COSAP [ (Committee for the Management of the Protected Area of Bezà Mahafaly ] and Madagascar National Parks.

“Song sharing between populations tends to happen more in the Northern Hemisphere where there are fewer physical barriers to movement of individuals between populations on the breeding grounds, where they do the majority of their singing. In some populations in the Southern Hemisphere song sharing appears to be more complex, with little song similarity within years but entire songs can spread to neighboring populations leading to song similarity across years,” said Dr. Melinda Rekdahl, marine conservation scientist for WCS’s Ocean Giants Program and lead author of the study. “Our study shows that this is not always the case in Southern Hemisphere populations, with similarities between both ocean basin songs occurring within years to different degrees over a 5-year period.”

The study authors examined humpback whale song recordings from both sides of the African continent–from animals off the coasts of Gabon and Madagascar respectively–and transcribed more than 1,500 individual sounds that were recorded between 2001-2005. Song similarity was quantified using statistical methods.

Male humpback whales are one of the animal kingdom’s most noteworthy singers, and individual animals sing complex compositions consisting of moans, cries, and other vocalizations called “song units.” Song units are composed into larger phrases, which are repeated to form “themes.” Different themes are produced in a sequence to form a song cycle that are then repeated for hours, or even days. For the most part, all males within the same population sing the same song type, and this population-wide song similarity is maintained despite continual evolution or change to the song leading to seasonal “hit songs.” Some song learning can occur between populations that are in close proximity and may be able to hear the other population’s song.

Over time, the researchers detected shared phrases and themes in both populations, with some years exhibiting more similarities than others. In the beginning of the study, whale populations in both locations shared five “themes.” One of the shared themes, however, had differences. Gabon’s version of Theme 1, the researchers found, consisted of a descending “cry-woop”, whereas the Madagascar singers split Theme 1 into two parts: a descending cry followed by a separate woop or “trumpet.”

Other differences soon emerged over time. By 2003, the song sung by whales in Gabon became more elaborate than their counterparts in Madagascar. In 2004, both population song types shared the same themes, with the whales in Gabon’s waters singing three additional themes. Interestingly, both whale groups had dropped the same two themes from the previous year’s song types. By 2005, songs being sung on both sides of Africa were largely similar, with individuals in both locations singing songs with the same themes and order. However, there were exceptions, including one whale that revived two discontinued themes from the previous year.

The study’s results stands in contrast to other research in which a song in one part of an ocean basin replaces or “revolutionizes” another population’s song preference. In this instance, the gradual changes and degrees of similarity shared by humpbacks on both sides of Africa was more gradual and subtle.

“Studies such as this one are an important means of understanding connectivity between different whale populations and how they move between different seascapes,” said Dr. Howard Rosenbaum, Director of WCS’s Ocean Giants Program and one of the co-authors of the new paper. “Insights on how different populations interact with one another and the factors that drive the movements of these animals can lead to more effective plans for conservation.”

The humpback whale is one of the world’s best-studied marine mammal species, well known for its boisterous surface behavior and migrations stretching thousands of miles. The animal grows up to 50 feet in length and has been globally protected from commercial whaling since the 1960s. WCS has studied humpback whales since that time and–as the New York Zoological Society–played a key role in the discovery that humpback whales sing songs. The organization continues to study humpback whale populations around the world and right here in the waters of New York; research efforts on humpback and other whales in New York Bight are currently coordinated through the New York Aquarium’s New York Seascape program.

I’m not able to embed the audio file here but, for the curious, there is a portion of a humpback whale song from Gabon here at EurekAlert.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the research paper,

Culturally transmitted song exchange between humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the southeast Atlantic and southwest Indian Ocean basins by Melinda L. Rekdahl, Ellen C. Garland, Gabriella A. Carvajal, Carissa D. King, Tim Collins, Yvette Razafindrakoto and Howard Rosenbaum. Royal Society Open Science 21 November 2018 Volume 5 Issue 11 https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.172305 Published:28 November 2018

This is an open access paper.