The process by which a cell engulfs matter is known as phagocytosis. One of the best known examples of failed phagocytosis is that of asbestos fibres in the lungs where lung cells have attempted to engulf a fibre that’s just too big and ends up piercing the cell. When enough of the cells are pierced, the person is diagnosed with mesothelioma.

This particular example of phagocytosis is a happier one according to a Dec. 16, 2016 article by Meghan Rosen for ScienceNews,

Human cells can snack on silicon.

Cells grown in the lab devour nano-sized wires of silicon through an engulfing process known as phagocytosis, scientists report December 16 in Science Advances.

Silicon-infused cells could merge electronics with biology, says John Zimmerman, a biophysicist now at Harvard University. “It’s still very early days,” he adds, but “the idea is to get traditional electronic devices working inside of cells.” Such hybrid devices could one day help control cellular behavior, or even replace electronics used for deep brain stimulation, he says.

Scientists have been trying to load electronic parts inside cells for years. One way is to zap holes in cells with electricity, which lets big stuff, like silicon nanowires linked to bulky materials, slip in. Zimmerman, then at the University of Chicago, and colleagues were looking for a simpler technique, something that would let tiny nanowires in easily and could potentially allow them to travel through a person’s bloodstream — like a drug.

A Dec. 22, 2016 University of Chicago news release by Matt Wood provides more detail,

“You can treat it as a non-genetic, synthetic biology platform,” said Bozhi Tian, PhD, assistant professor of chemistry and senior author of the new study. “Traditionally in biology we use genetic engineering and modify genetic parts. Now we can use silicon parts, and silicon can be internalized. You can target those silicon parts to specific parts of the cell and modulate that behavior with light.”

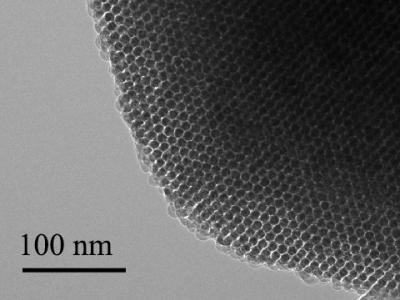

In the new study, Tian and his team show how cells consume or internalize the nanowires through phagocytosis, the same process they use to engulf and ingest nutrients and other particles in their environment. The nanowires are simply added to cell media, the liquid solution the cells live in, the same way you might administer a drug, and the cells take it from there. Eventually, the goal would be to inject them into the bloodstream or package them into a pill.

Once inside, the nanowires can interact directly with individual parts of the cell, organelles like the mitochondria, nucleus and cytoskeletal filaments. Researchers can then stimulate the nanowires with light to see how individual components of the cell respond, or even change the behavior of the cell. They can last up to two weeks inside the cell before biodegrading.

…

Seeing how individual parts of a cell respond to stimulation could give researchers insight into how medical treatments that use electrical stimulation work at a more detailed level. For instance, deep brain stimulation helps treat tremors from movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease by sending electrical signals to areas of the brain. Doctors know it works at the level of tissues and brain structures, but seeing how individual components of nerve cells react to these signals could help fine tune and improve the treatment.

The experiments in the study used umbilical vascular endothelial cells, which make up blood vessel linings in the umbilical cord. These cells readily took up the nanowires, but others, like cardiac muscle cells, did not. Knowing that some cells consume the wires and some don’t could also prove useful in experimental settings and give researchers more ways to target specific cell types.

Tian and his team manufactures the nanowires in their lab with a chemical vapor deposition system that grows the silicon structures to different specifications. They can adjust size, shape, and electrical properties as needed, or even add defects on purpose for testing. They can also make wires with porous surfaces that could deliver drugs or genetic material to the cells. The process gives them a variety of ways to manipulate the properties of the nanowires for research.

Seeing how individual parts of a cell respond to stimulation could give researchers insight into how medical treatments that use electrical stimulation work at a more detailed level. For instance, deep brain stimulation helps treat tremors from movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease by sending electrical signals to areas of the brain. Doctors know it works at the level of tissues and brain structures, but seeing how individual components of nerve cells react to these signals could help fine tune and improve the treatment.

The experiments in the study used umbilical vascular endothelial cells, which make up blood vessel linings in the umbilical cord. These cells readily took up the nanowires, but others, like cardiac muscle cells, did not. Knowing that some cells consume the wires and some don’t could also prove useful in experimental settings and give researchers more ways to target specific cell types.

Tian and his team manufactures the nanowires in their lab with a chemical vapor deposition system that grows the silicon structures to different specifications. They can adjust size, shape, and electrical properties as needed, or even add defects on purpose for testing. They can also make wires with porous surfaces that could deliver drugs or genetic material to the cells. The process gives them a variety of ways to manipulate the properties of the nanowires for research.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Cellular uptake and dynamics of unlabeled freestanding silicon nanowires by John F. Zimmerman, Ramya Parameswaran, Graeme Murray, Yucai Wang, Michael Burke, and Bozhi Tian. Science Advances 16 Dec 2016: Vol. 2, no. 12, e1601039 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1601039

This paper appears to be open access.