The opening reception for the Ian Wallace exhibition (Ian Wallace: Collected Works, May 27 to Sept. 30, 2017) at the Rennie Collection was a celebration of both Ian Wallace and Bob Rennie’s donation of 197 art works to the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa marking Canada’s 150th anniversary. Here’s more about the gift from a May 9, 2017 Rennie Collection notice (received via email),

In celebration of Canada’s 150th birthday, we are donating 197 paintings, sculptures and mixed-media pieces made by some of the most well-known and established Canadian and international artists working today to the National Gallery of Canada!

This is the largest gift of contemporary art ever received by the National Gallery, with major pieces created by internationally renowned artists, such as Colombian Doris Salcedo, as well as important Vancouver based artists Brian Jungen, Damian Moppett, Rodney Graham, Ian Wallace [emphasis mine], and Geoffrey Farmer, who is Canada’s selection for the 57th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia.

Getting back to the Ian Wallace exhibition,

The commentary that follows are my impressions of the show, your mileage may vary.

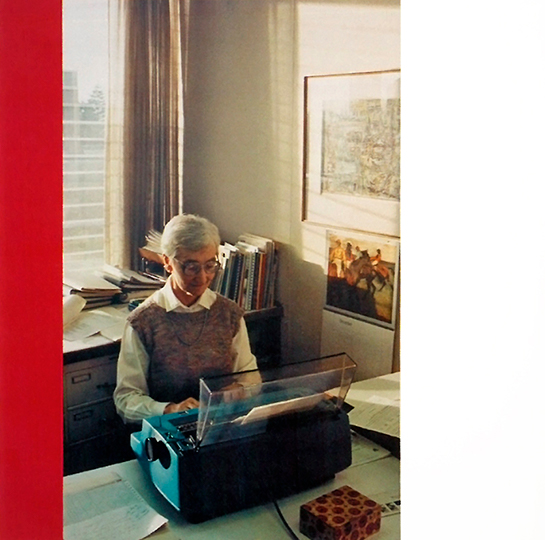

What I found most intriguing was the ‘squareness’ of it all with its prevalence of frames/boxes. For example the image above is framed with red and white (paint on plywood) at the sides and within the image, there’s the window, the calendar, the photograph, a markedly squarish electric typewriter, a box on the desk, the cabinet behind the typist, and the books on the cabinet. One image could be a coincidence but when you’re surrounded by room after room with these framed/boxed images of more frames and boxes, well, happenstance has to be rejected.

Wallace is a photographer-artist, one of the individuals in Vancouver, Canada, who founded photoconceptualism (I sometimes mistakenly refer to this as photorealism). As you may have guessed from my parenthesized comment, I’m not a big fan of this movement or school. However, I’ve found that enjoyment or fandom isn’t necessarily the point where contemporary art is concerned. My experience is that contemporary art is largely intellectual rather than sensual. Sculptures, paintings, textiles, etc. are more sensual by nature where many contemporary pieces begin their existence in a machinist’s shop or via a piece of equipment such as a camera or as an algorithm.

To attend an exhibition of contemporary art, explanation is needed and thankfully the Rennie provides a tour guide providing insight into the artist and their work. In Wallace’s case (kudos, by the way, to Sydney who led the tour I attended), he’s a professor of art history whose main means of expression is photography and much of his focus is on the production of art.

For me though, it was all about square edges, frames, and boxes—an obvious association given that you frame your subject (inadvertently or not) when taking a photograph. There are images and pieces that don’t fit into my ‘square’ obsession but the number in this exhibition that did is amazing and dizzying. I got to the point where I was giddy enough to think of each room as yet another box/frame and we were the subjects leading to these questions: who is seeing, who is being seen, and what is being seen?

The fourth question: how we were seeing the images came up in the context of the show, more specifically, when viewing Wallace’s ‘Poverty 1980 – 1984’ series. It’s considered one of Wallace’s earlier works and like many of his pieces is a series of images. According to Sydney, Wallace is critiquing how we view poverty. In his view, poverty and images of poverty are often glamourized and to draw attention to that he had friends dress up as bohemians from an earlier period and pose in some of Vancouver’s dicier streets and alleyways. It’s not easy to see the images as they are indistinct and washed over in one colour or another.

Before commenting on this piece, I’ve got an excerpt from the Rennie Collection’s undated [?} press release,

Rennie Museum is pleased to announce a solo exhibition featuring rarely and never–before seen historic works of renowned Vancouver artist Ian Wallace. Highlighting Wallace’s perennial exploration of social issues, the works presented will also examine the crux of his artistic process: the intersectionality between public and private, personal and universal, process and production, abstraction and representation. The exhibition runs May 27 to September 30, 2017.

Included in the exhibition will be Poverty 1980 – 1984, a multimedia installation comprising of film, painting, and photography. Initially enacted in 1980 as a 16mm film commenting on the tradition of documentary film–making, the Poverty project offers variations on a single theme. By employing friends and colleagues to act out scenes of bohemian scarcity in Vancouver, Wallace creates fictionalized simulacra—an aestheticized model of poverty derived from our collective, often over–embellished, social conscious. [emphasis mine] The film stills are then abstracted through repetition and presented amidst monochromatic colour fields, prompting viewers to review their own cognitive processes.

…

I think I understand what is being described in the news release and I agree that poverty can be ‘aestheticized’ or made glamourous. In fact, there’s a term for it ‘poverty porn’. I first heard the term in relation to a series of images taken by Lincoln Clarkes and his series, Heroines (from his Wikipedia entry; Note: Links have been removed),

Heroines (Anvil Press) [3] is an epic photographic documentary of 400 addicted women of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, which won the 2003 Vancouver Book Award (in a tie with Stan Douglas), and was the subject of numerous philosophical essays (by Leigh Butler, Margot Leigh Butler, and Paul Ugor, among them). The London Observer said Clarkes’ book offered “beauty in a beastly place.” Globe and Mail called it “intimate, compelling and undeniably unsettling,” while The Toronto Star called it “incredibly powerful.”

Clarkes, who’d been a high end fashion photographer, took photographs of female addicts (hence heroin/heroine) living in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, an area which by then was and still is a national and international disgrace. Within the Downtown Eastside community there was a great deal of controversy over Clarke’s work hence the whispers about ‘poverty porn’.

I gather Clarkes’ initial impulse was to treat the women with respect and kindness and to try framing ‘addicts’ in the same way as he would a high fashion model rather than as one of the ‘wretched of the earth’. Unfortunately as the work evolved, it appeared to become a career stepping stone for him and any other concerns seemed to drop out of view. In the end, I couldn’t escape the impression that these women had been used again as unintentional as it may have been.

Getting back to Wallace, I see his point but I don’t understand how his hard-to-see images of fake bohemians in streets and alleyways that are unrecognizable even to a local make his point about glamourizing poverty. Presumably, Wallace’s images were taken in the Downtown Eastside, which in the 1980s was not nearly in the straits it is today. The social safety net cuts that came in the mid to later 1980s and the diminishment of the federal transfer funds to the provinces weren’t yet the stuff of nightmares for social activists.

In retrospect, Wallace’s images seem weirdly prescient, a kind of ‘fiddling while Rome burns ‘view of the future which is now our present day but, for me, they don’t exactly deglamourize poverty or give us a view of an “… over–embellished, social conscious.” In fact, there’s something a bit odd about seeing this piece in a gallery that is housed in the same building as Rennie’s real estate marketing business in a rapidly gentrifying area just a block or two away from where those ‘poverty images’ were taken. Add in the fact that the tour was made up of a relatively middle class group of people staring at poverty when the reality is block away the whole thing becomes head-spinning as these questions whirl who is seeing, who is being seen, and what is being seen?

The last piece I’m going to mention is the multi-panel “The Idea of the University” (1990). The piece brought back memories as I once worked at the University of British Columbia where Wallace took his images. It was a walk down the lane of ‘old technology’ with microfiche readers, electric typewriters, card catalogues, etc. Sydney Marshall (tour guide Sydney) has written a July 25, 2017 essay about the piece on the Rennie Collection’s website,

…

Without contest, my favourite artwork by Ian Wallace is The Idea of the University (1990). Installed in Rennie Museum’s monumental four-storey high exhibition space, the sprawling canvasses are almost as immense as their depicted subject: the University of British Columbia. It’s likely that I appreciate it so much because like Wallace, I also studied at U.B.C., sitting in the same lecture hall that he used to teach in. This sentimentality seems to be shared; local visitors will often stop to point out former professors, or remember old buildings that have since been demolished. The piece is an exercise in collective memory. Functioning like a time capsule, it allows viewers to reflect on developments from the past to present. This is, however, just one aspect of a multi-faceted piece. By using the competing technical modes of painting and photography to depict university spaces, Wallace challenges the notion that painting is the only valid form of artistic production within academia. Historically, art production has operated within a technical hierarchy, with painting as the most revered medium due to the artistic labour it necessitates. The 20th century’s shifting social climate ultimately sees a redistribution of this hierarchical power. In response to the increasing corporatization of the university space, anti-institutional dissent permeated universities across the North American continent – U.B.C. included. For Ian Wallace and his contemporaries, this manifested as a desire to dispute traditional designations of painting as the most inherently valuable way to produce art. With his work, Wallace recontextualizes the medium, placing it in direct conversation with its subsidiaries: photography, writing, and thinking. In doing so, he subverts the idea that a technical hierarchy needs exist at all, equating multiple forms of production across a broad spectrum of intellectual and artistic interests.

Conceived for a special exhibition at the U.B.C. Fine Arts Gallery in 1990, the work features sixteen photographs of university spaces and personnel in various states of candidness, each flanked with bars of white and multicoloured monochrome. In its entirety, the work looks cinematic – as if it were a filmstrip of image stills pulled from a promotional clip. This is not to say the images are typically beautiful because, by all accounts, they’re not. The depicted spaces are not inherently exciting. Some photographs are oddly cropped, others slightly out of focus; these formal details are irrelevant to the medium’s intended purpose: its subject. Photography, as a medium, offers to art that which painting cannot. The photograph is able to capture the totality of ‘the everyday’ as it exists in a moment, bringing banality into focus and calling the viewer to engage with it further. Visible beauty no longer designates whether a work is ‘art’ or ‘not art’; instead, it is the depth of concept that provides this justification. The valorization of these images as ‘art’ is additionally supported by their proximity to monochrome painting. The white monochrome acts as grounding, a symbolic representation of the white-walled gallery space typically designating a work of art. The multicoloured inclusions operate similarly. Different on each canvas, the monochrome bars provide an aesthetic and historical reference to modernism that further situates the opposing photographs within an established artistic context. By referencing this history, Wallace is able to push the limit of acceptable artistic production, using the predetermined power of modernism to elevate the comparatively new medium of photography.

It should be noted that a key component of The Idea of the University is missing from its visual representation: Wallace’s catalogue essay. The writing has become a near immovable companion to the work, as it explains precisely why the artist has chosen to explore the subject of the university. In it, Wallace identifies the contemporary university as an abstracted space, caught between its founding principles and modern-day realities. The university is supposed to be a universalizing space, providing equal opportunity to acquire ‘truth’ and knowledge to everyone that passes through its metaphorical gates. Wallace almost immediately invalidates this idea by identifying the discrepancy between this ideal image and its actuality*. Instead of a collective organization united in the unhindered production of knowledge, the contemporary university exists as an ideology-producing institution that services a number of specific political and socioeconomic interests*. For Wallace, the same designation could be given to the discourse of art – a supposedly universal field that relies almost entirely on individual notions of taste and arbitrary economic determinations. The Idea of the University works as an evaluation of both the university and the discourse of art, but Wallace very intentionally leaves the canvasses open-ended. Instead, he presents the failures (or at least, potential failures) of these systems in his writing, using its visual counterpart as a stimulus by which the viewer can judge the validity of his propositions for themselves.

Just as Wallace succeeds in neutrally depicting the university space, so too does he succeed in avoiding a singular narrative of exactly how knowledge is produced. He chooses not to privilege one form of ‘work’ over another, but does show immense regard for practice in general. Some empty and others full, most of the photographed spaces feature a single figure engaging in various forms of intellectual labour: reading, searching the web, or completing administrative tasks. All of these engagements are qualified as ‘work’ that contributes to the ultimate output of the university. This is paralleled by Wallace’s own technical expansions of artistic labour. He challenges traditional perceptions of painting and photography by combining the two, then supplementing the combination with writing. In this sense, it is neither the visual nor the written work that takes precedence, but the idea that all of these productive forms are equally valid. In essence, Wallace’s presentation of simultaneous forms of labour democratizes realms of production within art, decentralizing painting as the foundation upon which art must be based. Not only does artwork not need to be painted, it doesn’t even have to be visual. To Ian Wallace, a radical thought is as legitimate an artistic gesture as a visible brushstroke.

* Wallace, Ian. “The Idea of the University.” UBC Fine Arts Gallery, 1990. Page 23. Print.

The production of art and the production of knowledge would seem to be the dominant themes of this Ian Wallace exhibition and, I suspect, his life.

Anyone interested in seeing the show for themselves, can go here to save a space on one of the tours (for this show they are on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays). It is also possible to book separate tours for groups of eight or more here.