At very long last, here’s our (Raewyn Turner’s and my) video, Steep (1): A digital poetry of gold nanoparticles which was presented at the 2015 International Symposium (ISEA) held in Vancouver in August 2015,

There’s more about the project and my participation (poetry) with Raewyn Turner, a visual artist from New Zealand, in an April 24, 2015 posting (scroll down about 75% of the way).

Monthly Archives: January 2016

Cellulose-based nanogenerators to power biomedical implants?

This cellulose nanogenerator research comes from India. A Jan. 27, 2016 American Chemical Society (ACS) news release makes the announcement,

Implantable electronics that can deliver drugs, monitor vital signs and perform other health-related roles are on the horizon. But finding a way to power them remains a challenge. Now scientists have built a flexible nanogenerator out of cellulose, an abundant natural material, that could potentially harvest energy from the body — its heartbeats, blood flow and other almost imperceptible but constant movements. …

Efforts to convert the energy of motion — from footsteps, ocean waves, wind and other movement sources — are well underway. Many of these developing technologies are designed with the goal of powering everyday gadgets and even buildings. As such, they don’t need to bend and are often made with stiff materials. But to power biomedical devices inside the body, a flexible generator could provide more versatility. So Md. Mehebub Alam and Dipankar Mandal at Jadavpur University in India set out to design one.

The researchers turned to cellulose, the most abundant biopolymer on earth, and mixed it in a simple process with a kind of silicone called polydimethylsiloxane — the stuff of breast implants — and carbon nanotubes. Repeated pressing on the resulting nanogenerator lit up about two dozen LEDs instantly. It also charged capacitors that powered a portable LCD, a calculator and a wrist watch. And because cellulose is non-toxic, the researchers say the device could potentially be implanted in the body and harvest its internal stretches, vibrations and other movements [also known as, harvesting biomechanical motion].

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Native Cellulose Microfiber-Based Hybrid Piezoelectric Generator for Mechanical Energy Harvesting Utility by

Md. Mehebub Alam and Dipankar Mandal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2016, 8 (3), pp 1555–1558 DOI: 10.1021/acsami.5b08168 Publication Date (Web): January 11, 2016Copyright © 2016 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

I did take a peek at the paper to see if I could determine whether or not they had used wood-derived cellulose and whether cellulose nanocrystals had been used. Based on the references cited for the paper, I think the answer to both questions is yes.

My latest piece on harvesting biomechanical motion is a June 24, 2014 post where I highlight a research project in Korea and another one in the UK and give links to previous posts on the topic.

Constructing a liver

Chinese researchers have taken a step closer to constructing complex (lifelike) liver tissue according to a Jan. 27, 2016 American Chemical Society (ACS) news release (also on EurekAlert),

Engineered liver tissue could have a range of important uses, from transplants in patients suffering from the organ’s failure to pharmaceutical testing [this usage is sometimes known as liver-on-a-chip]. Now scientists report in ACS’ journal Analytical Chemistry the development of such a tissue, which closely mimics the liver’s complicated microstructure and function more effectively than existing models.

The liver serves a critical role in digesting food and detoxifying the body. But due to a variety of factors, including viral infections, alcoholism and drug reactions, the organ can develop chronic or acute problems. When it doesn’t work well, a person can suffer abdominal pain, swelling, nausea and other symptoms. Complete liver failure can be life-threatening and can require a transplant, a procedure that currently depends on human donors. To curtail this reliance and provide an improved model for predicting drugs’ side effects, scientists have been engineering liver tissue in the lab. But so far, they haven’t achieved the complex architecture of the real thing. Jinyi Wang and colleagues came up with a new approach.

Wang’s team built a microfluidics-based tissue that copies the liver’s complex lobules, the organ’s tiny structures that resemble wheels with spokes. They did this with human cells from a liver and an aorta, the body’s main artery. In the lab, the engineered tissue had a metabolic rate that was closer to real-life levels than other liver models, and it successfully simulated how a real liver would react to various drug combinations. The researchers conclude their approach could lead to the development of functional liver tissue for clinical applications and screening drugs for side effects and potentially harmful interactions.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

On-Chip Construction of Liver Lobule-like Microtissue and Its Application for Adverse Drug Reaction Assay by Chao Ma, Lei Zhao, En-Min Zhou, Juan Xu, Shaofei Shen, and Jinyi Wang. Northwest A&F University, China Anal. Chem., Article ASAP DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03869 Publication Date (Web): January 7, 2016

Copyright © 2016 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

In a teleconference earlier this month (January 2016), I spoke to researchers at the University of Malaya, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), and Harvard University about a joint lung and nanomedicine research project where I asked researcher Joseph Brain (Harvard) about using lung-on-a-chip testing in place of in vivo (animal) testing and he indicated more confidence in the ‘precision cut lung slices’ technique. (You can find out more about the Malaysian project in my Jan. 12, 2016 posting but there’s only a brief mention of Brain’s preferred alternative animal testing technique.)

January 31, 2016 deadlines for early bird tickets (ESOF) and conference abstracts (emerging technologies)

ESOF 2016 (EuroScience Open Forum)

Early bird tickets for this biennial science conference are available until Jan. 31, 2016 according to a Jan. 18, 2016 email notice,

Our most affordable tickets are available to purchase until the end of the month, so make sure you get yours before they disappear. Prices start from only £75 for a full four-day pass for early careers researchers (up to 5 years post doc), and £225 for a full delegate pass. All registrations are entitled to a year long complimentary subscription to Nature at this time.

You can also book your accommodation when you register to attend ESOF. We have worked hard with our city partners to bring you the best deals for your stay in Manchester. With the summer set to be busy with not only ESOF but major international sporting events, make sure you take advantage of these deals.

To register to attend please click here

You can find out more about the event which takes place from July 23 – 27, 2016 in Manchester, England here and/or you can watch this video,

For any interested journalists, media registration has opened (from the Jan. 18, 2016 notice),

Media registration opens

We are delighted to announce our ESOF press accreditation is available for journalists and science communications professionals to register for the conference. Accreditation provides complimentary access to the full ESOF programme, social events and a range of exclusive press only activities. Further details of the eligibility criteria and registration process can be found here.

Nature Publishing Group offers journalists a travel grant which will cover most if not all the expenses associated with attending 2016 ESOF (from the ESOF Nature Travel Grant webpage),

The Nature Travel Grant Scheme offers journalists and members of media organisations from around the world the opportunity to attend ESOF for free. The grant offers complimentary registration as well as help covering travel and accommodation costs.

1. Purpose

Created by EuroScience, the biennial ESOF – EuroScience Open Forum – meeting is the largest pan-European general science conference dedicated to scientific research and innovation. At ESOF meetings leading scientists, researchers, journalists, business people, policy makers and the general public from all over the world discuss new discoveries and debate the direction that research is taking in the sciences, humanities and social sciences.

Springer Nature is a leading global research, educational and professional publisher, home to an array of respected and trusted brands providing quality content through a range of innovative products and services, including the journal Nature. Springer Nature was formed in 2015 through the merger of Nature Publishing Group, Palgrave Macmillan, Macmillan Education and Springer Science+Business Media. Nature Publishing Group has supported ESOF since its very first meeting in 2004.

Similar to the 2012 and 2014 edition of meeting, Springer Nature is funding the Nature Travel Grant Scheme for journalists to attend ESOF2016 with the aim to increase the impact of ESOF.

2. The Scheme

In addition to free registration, the Nature Travel Grant Scheme offers a lump sum of £450 for UK based journalists, £600 for journalists based in Europe and £800 for journalists based outside of Europe, to help cover the costs of travel and accommodation to attend ESOF2016.

3. Who can apply?

All journalists irrespective of their gender, age, nationality, place of residence and media type (paper, radio, TV, web) are welcome to apply. Media accreditation will be required.

4. Application procedure

To submit an application sign into the EuroScience Conference and Membership Platform (ESCMP) and click on “Apply for a Grant”. Follow the application procedure.

On submitting the application form for travel grants, you agree to the full acceptance of the rules and to the decision taken by the Selection Committee.

The deadline for submitting an application is February 29th 2016, 12:00 pm CET.

…

Good luck!

4th Annual Governance of Emerging Technologies: Law, Policy and Ethics Conference

Here’s more about the conference (deadline for abstracts is Jan. 31, 2016) from the conference’s Call for Abstract’s webpage,

Fourth Annual Conference on

Governance of Emerging Technologies: Law, Policy, and EthicsMay 24-26, 2016, Tempe, Arizona

Call for abstracts:

The co-sponsors invite submission of abstracts for proposed presentations. Submitters of abstracts need not provide a written paper, although provision will be made for posting and possible post-conference publication of papers for those presenters interested in such options. Although abstracts are invited for any aspect or topic relating to the governance of emerging technologies, some particular themes that will be emphasized at this year’s conference include existential or catastrophic risks, governance implications of algorithms, resilience and emerging technologies, artificial intelligence, military technologies, and gene editing.

Abstracts should not exceed 500 words.

Abstracts must be submitted by January 31, 2016 to be considered.

Decisions on abstracts will be made by the program committee and communicated by February 29 [2016].Funding: The sponsors will pay for the conference registration (including all conference meals) for one presenter for each accepted abstract. In addition, we will have limited funds available for travel subsidies in whole or in part. After completing your abstract online, you will be asked if you wish to apply for a travel subsidy. Any such additional funding will be awarded based on the strength of the abstract, demonstration of financial need, and/or the potential to encourage student authors and early-career scholars. Accepted presenters for whom conference funding is not available will need to pay their own transportation and hotel costs.

…

For more information, please contact Lauren Burkhart at Lauren.Burkhart@asu.edu.

You don’t often see conference organizers offering to pay registration and meals for a single presenter from each accepted submission. Good luck!

When an atom more or less makes a big difference

As scientists continue exploring the nanoscale, it seems that finding the number of atoms in your particle makes a difference is no longer so surprising. From a Jan. 28, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

Combining experimental investigations and theoretical simulations, researchers have explained why platinum nanoclusters of a specific size range facilitate the hydrogenation reaction used to produce ethane from ethylene. The research offers new insights into the role of cluster shapes in catalyzing reactions at the nanoscale, and could help materials scientists optimize nanocatalysts for a broad class of other reactions.

A Jan. 28, 2016 Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) news release (*also on EurekAlert*), which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

At the macro-scale, the conversion of ethylene has long been considered among the reactions insensitive to the structure of the catalyst used. However, by examining reactions catalyzed by platinum clusters containing between 9 and 15 atoms, researchers in Germany and the United States found that at the nanoscale, that’s no longer true. The shape of nanoscale clusters, they found, can dramatically affect reaction efficiency.

While the study investigated only platinum nanoclusters and the ethylene reaction, the fundamental principles may apply to other catalysts and reactions, demonstrating how materials at the very smallest size scales can provide different properties than the same material in bulk quantities. …

“We have re-examined the validity of a very fundamental concept on a very fundamental reaction,” said Uzi Landman, a Regents’ Professor and F.E. Callaway Chair in the School of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “We found that in the ultra-small catalyst range, on the order of a nanometer in size, old concepts don’t hold. New types of reactivity can occur because of changes in one or two atoms of a cluster at the nanoscale.”

The widely-used conversion process actually involves two separate reactions: (1) dissociation of H2 molecules into single hydrogen atoms, and (2) their addition to the ethylene, which involves conversion of a double bond into a single bond. In addition to producing ethane, the reaction can also take an alternative route that leads to the production of ethylidyne, which poisons the catalyst and prevents further reaction.

The project began with Professor Ueli Heiz and researchers in his group at the Technical University of Munich experimentally examining reaction rates for clusters containing 9, 10, 11, 12 or 13 platinum atoms that had been placed atop a magnesium oxide substrate. The 9-atom nanoclusters failed to produce a significant reaction, while larger clusters catalyzed the ethylene hydrogenation reaction with increasingly better efficiency. The best reaction occurred with 13-atom clusters.

Bokwon Yoon, a research scientist in Georgia Tech’s Center for Computational Materials Science, and Landman, the center’s director, then used large-scale first-principles quantum mechanical simulations to understand how the size of the clusters – and their shape – affected the reactivity. Using their simulations, they discovered that the 9-atom cluster resembled a symmetrical “hut,” while the larger clusters had bulges that served to concentrate electrical charges from the substrate.

“That one atom changes the whole activity of the catalyst,” Landman said. “We found that the extra atom operates like a lightning rod. The distribution of the excess charge from the substrate helps facilitate the reaction. Platinum 9 has a compact shape that doesn’t facilitate the reaction, but adding just one atom changes everything.”

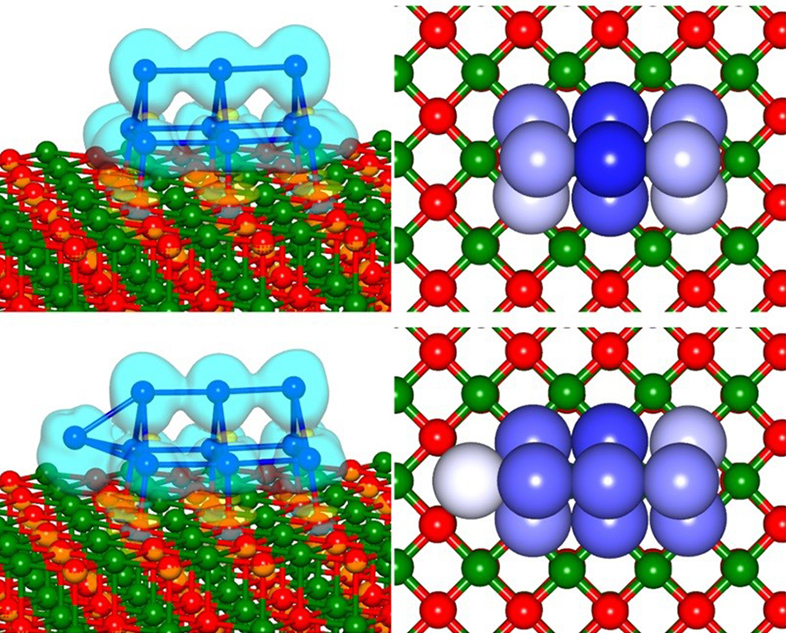

Here’s an illustration featuring the difference between a 9 atom cluster and a 10 atom cluster,

A single atom makes a difference in the catalytic properties of platinum nanoclusters. Shown are platinum 9 (top) and platinum 10 (bottom). (Credit: Uzi Landman, Georgia Tech)

The news release explains why the larger clusters function as catalysts,

Nanoclusters with 13 atoms provided the maximum reactivity because the additional atoms shift the structure in a phenomena Landman calls “fluxionality.” This structural adjustment has also been noted in earlier work of these two research groups, in studies of clusters of gold [emphasis mine] which are used in other catalytic reactions.

“Dynamic fluxionality is the ability of the cluster to distort its structure to accommodate the reactants to actually enhance reactivity,” he explained. “Only very small aggregates of metal can show such behavior, which mimics a biochemical enzyme.”

The simulations showed that catalyst poisoning also varies with cluster size – and temperature. The 10-atom clusters can be poisoned at room temperature, while the 13-atom clusters are poisoned only at higher temperatures, helping to account for their improved reactivity.

“Small really is different,” said Landman. “Once you get into this size regime, the old rules of structure sensitivity and structure insensitivity must be assessed for their continued validity. It’s not a question anymore of surface-to-volume ratio because everything is on the surface in these very small clusters.”

While the project examined only one reaction and one type of catalyst, the principles governing nanoscale catalysis – and the importance of re-examining traditional expectations – likely apply to a broad range of reactions catalyzed by nanoclusters at the smallest size scale. Such nanocatalysts are becoming more attractive as a means of conserving supplies of costly platinum.

“It’s a much richer world at the nanoscale than at the macroscopic scale,” added Landman. “These are very important messages for materials scientists and chemists who wish to design catalysts for new purposes, because the capabilities can be very different.”

Along with the experimental surface characterization and reactivity measurements, the first-principles theoretical simulations provide a unique practical means for examining these structural and electronic issues because the clusters are too small to be seen with sufficient resolution using most electron microscopy techniques or traditional crystallography.

“We have looked at how the number of atoms dictates the geometrical structure of the cluster catalysts on the surface and how this geometrical structure is associated with electronic properties that bring about chemical bonding characteristics that enhance the reactions,” Landman added.

I highlighted the news release’s reference to gold nanoclusters as I have noted the number issue in two April 14, 2015 postings, neither of which featured Georgia Tech, Gold atoms: sometimes they’re a metal and sometimes they’re a molecule and Nature’s patterns reflected in gold nanoparticles.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the ‘platinum catalyst’ paper,

Structure sensitivity in the nonscalable regime explored via catalysed ethylene hydrogenation on supported platinum nanoclusters by Andrew S. Crampton, Marian D. Rötzer, Claron J. Ridge, Florian F. Schweinberger, Ueli Heiz, Bokwon Yoon, & Uzi Landman. Nature Communications 7, Article number: 10389 doi:10.1038/ncomms10389 Published 28 January 2016

This paper is open access.

*’also on EurekAlert’ added Jan. 29, 2016.

Cambridge University researchers tell us why Spiderman can’t exist while Stanford University proves otherwise

A team of zoology researchers at Cambridge University (UK) find themselves in the unenviable position of having their peer-reviewed study used as a source of unintentional humour. I gather zoologists (Cambridge) and engineers (Stanford) don’t have much opportunity to share information.

A Jan. 18, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily announces the Cambridge research findings,

Latest research reveals why geckos are the largest animals able to scale smooth vertical walls — even larger climbers would require unmanageably large sticky footpads. Scientists estimate that a human would need adhesive pads covering 40% of their body surface in order to walk up a wall like Spiderman, and believe their insights have implications for the feasibility of large-scale, gecko-like adhesives.

A Jan. 18, 2016 Cambridge University press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the research and the thinking that led to the researchers’ conclusions,

Dr David Labonte and his colleagues in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology found that tiny mites use approximately 200 times less of their total body area for adhesive pads than geckos, nature’s largest adhesion-based climbers. And humans? We’d need about 40% of our total body surface, or roughly 80% of our front, to be covered in sticky footpads if we wanted to do a convincing Spiderman impression.

Once an animal is big enough to need a substantial fraction of its body surface to be covered in sticky footpads, the necessary morphological changes would make the evolution of this trait impractical, suggests Labonte.

“If a human, for example, wanted to walk up a wall the way a gecko does, we’d need impractically large sticky feet – our shoes would need to be a European size 145 or a US size 114,” says Walter Federle, senior author also from Cambridge’s Department of Zoology.

The researchers say that these insights into the size limits of sticky footpads could have profound implications for developing large-scale bio-inspired adhesives, which are currently only effective on very small areas.

“As animals increase in size, the amount of body surface area per volume decreases – an ant has a lot of surface area and very little volume, and a blue whale is mostly volume with not much surface area” explains Labonte.

“This poses a problem for larger climbing species because, when they are bigger and heavier, they need more sticking power to be able to adhere to vertical or inverted surfaces, but they have comparatively less body surface available to cover with sticky footpads. This implies that there is a size limit to sticky footpads as an evolutionary solution to climbing – and that turns out to be about the size of a gecko.”

Larger animals have evolved alternative strategies to help them climb, such as claws and toes to grip with.

The researchers compared the weight and footpad size of 225 climbing animal species including insects, frogs, spiders, lizards and even a mammal.

“We compared animals covering more than seven orders of magnitude in weight, which is roughly the same as comparing a cockroach to the weight of Big Ben, for example,” says Labonte.

These investigations also gave the researchers greater insights into how the size of adhesive footpads is influenced and constrained by the animals’ evolutionary history.

“We were looking at vastly different animals – a spider and a gecko are about as different as a human is to an ant- but if you look at their feet, they have remarkably similar footpads,” says Labonte.

“Adhesive pads of climbing animals are a prime example of convergent evolution – where multiple species have independently, through very different evolutionary histories, arrived at the same solution to a problem. When this happens, it’s a clear sign that it must be a very good solution.”

The researchers believe we can learn from these evolutionary solutions in the development of large-scale manmade adhesives.

“Our study emphasises the importance of scaling for animal adhesion, and scaling is also essential for improving the performance of adhesives over much larger areas. There is a lot of interesting work still to do looking into the strategies that animals have developed in order to maintain the ability to scale smooth walls, which would likely also have very useful applications in the development of large-scale, powerful yet controllable adhesives,” says Labonte.

There is one other possible solution to the problem of how to stick when you’re a large animal, and that’s to make your sticky footpads even stickier.

“We noticed that within closely related species pad size was not increasing fast enough to match body size, probably a result of evolutionary constraints. Yet these animals can still stick to walls,” says Christofer Clemente, a co-author from the University of the Sunshine Coast [Australia].

“Within frogs, we found that they have switched to this second option of making pads stickier rather than bigger. It’s remarkable that we see two different evolutionary solutions to the problem of getting big and sticking to walls,” says Clemente.

“Across all species the problem is solved by evolving relatively bigger pads, but this does not seem possible within closely related species, probably since there is not enough morphological diversity to allow it. Instead, within these closely related groups, pads get stickier. This is a great example of evolutionary constraint and innovation.”

A researcher at Stanford University (US) took strong exception to the Cambridge team’s conclusions , from a Jan. 28, 2016 article by Michael Grothaus for Fast Company (Note: A link has been removed),

It seems the dreams of the web-slinger’s fans were crushed forever—that is until a rival university swooped in and saved the day. A team of engineers working with mechanical engineering graduate student Elliot Hawkes at Stanford University have announced [in 2014] that they’ve invented a device called “gecko gloves” that proves the Cambridge researchers wrong.

Hawkes has created a video outlining the nature of his dispute with Cambridge University and US tv talk show host, Stephen Colbert who featured the Cambridge University research in one of his monologues,

To be fair to Hawkes, he does prove his point. A Nov. 21, 2014 Stanford University report by Bjorn Carey describes Hawke’s ingenious ‘sticky pads,

Each handheld gecko pad is covered with 24 adhesive tiles, and each of these is covered with sawtooth-shape polymer structures each 100 micrometers long (about the width of a human hair).

The pads are connected to special degressive springs, which become less stiff the further they are stretched. This characteristic means that when the springs are pulled upon, they apply an identical force to each adhesive tile and cause the sawtooth-like structures to flatten.

“When the pad first touches the surface, only the tips touch, so it’s not sticky,” said co-author Eric Eason, a graduate student in applied physics. “But when the load is applied, and the wedges turn over and come into contact with the surface, that creates the adhesion force.”

As with actual geckos, the adhesives can be “turned” on and off. Simply release the load tension, and the pad loses its stickiness. “It can attach and detach with very little wasted energy,” Eason said.

The ability of the device to scale up controllable adhesion to support large loads makes it attractive for several applications beyond human climbing, said Mark Cutkosky, the Fletcher Jones Chair in the School of Engineering and senior author on the paper.

“Some of the applications we’re thinking of involve manufacturing robots that lift large glass panels or liquid-crystal displays,” Cutkosky said. “We’re also working on a project with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to apply these to the robotic arms of spacecraft that could gently latch on to orbital space debris, such as fuel tanks and solar panels, and move it to an orbital graveyard or pitch it toward Earth to burn up.”

Previous work on synthetic and gecko adhesives showed that adhesive strength decreased as the size increased. In contrast, the engineers have shown that the special springs in their device make it possible to maintain the same adhesive strength at all sizes from a square millimeter to the size of a human hand.

The current version of the device can support about 200 pounds, Hawkes said, but, theoretically, increasing its size by 10 times would allow it to carry almost 2,000 pounds.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the Stanford paper,

Human climbing with efficiently scaled gecko-inspired dry adhesives by Elliot W. Hawkes, Eric V. Eason, David L. Christensen, Mark R. Cutkosky. Jurnal of the Royal Society Interface DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0675 Published 19 November 2014

This paper is open access.

To be fair to the Cambridge researchers, It’s stretching it a bit to say that Hawke’s gecko gloves allow someone to be like Spiderman. That’s a very careful, slow climb achieved in a relatively short period of time. Can the human body remain suspended that way for more than a few minutes? How big do your sticky pads have to be if you’re going to have the same wall-climbing ease of movement and staying power of either a gecko or Spiderman?

Here’s a link to and a citation for the Cambridge paper,

Extreme positive allometry of animal adhesive pads and the size limits of adhesion-based climbing by David Labonte, Christofer J. Clemente, Alex Dittrich, Chi-Yun Kuo, Alfred J. Crosby, Duncan J. Irschick, and Walter Federle. PNAS doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519459113

This paper is behind a paywall but there is an open access preprint version, which may differ from the PNAS version, available,

Extreme positive allometry of animal adhesive pads and the size limits of adhesion-based climbing by David Labonte, Christofer J Clemente, Alex Dittrich, Chi-Yun Kuo, Alfred J Crosby, Duncan J Irschick, Walter Federle. bioRxiv

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/033845

I hope that if the Cambridge researchers respond, they will be witty rather than huffy. Finally, there’s this gecko image (which I love) from the Cambridge researchers,

Origami and our pop-up future

They should have declared Jan. 25, 2016 ‘L. Mahadevan Day’ at Harvard University. The researcher was listed as an author on two major papers. I covered the first piece of research, 4D printed hydrogels, in this Jan. 26, 2016 posting. Now for Mahadevan’s other work, from a Jan. 27, 2016 news item on Nanotechnology Now,

What if you could make any object out of a flat sheet of paper?

That future is on the horizon thanks to new research by L. Mahadevan, the Lola England de Valpine Professor of Applied Mathematics, Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, and Physics at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). He is also a core faculty member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, and member of the Kavli Institute for Bionano Science and Technology, at Harvard University.

Mahadevan and his team have characterized a fundamental origami fold, or tessellation, that could be used as a building block to create almost any three-dimensional shape, from nanostructures to buildings. …

A Jan. 26, 2016 Harvard University news release by Leah Burrows, which originated the news item, provides more detail about the specific fold the team has been investigating,

The folding pattern, known as the Miura-ori, is a periodic way to tile the plane using the simplest mountain-valley fold in origami. It was used as a decorative item in clothing at least as long ago as the 15th century. A folded Miura can be packed into a flat, compact shape and unfolded in one continuous motion, making it ideal for packing rigid structures like solar panels. It also occurs in nature in a variety of situations, such as in insect wings and certain leaves.

“Could this simple folding pattern serve as a template for more complicated shapes, such as saddles, spheres, cylinders, and helices?” asked Mahadevan.

“We found an incredible amount of flexibility hidden inside the geometry of the Miura-ori,” said Levi Dudte, graduate student in the Mahadevan lab and first author of the paper. “As it turns out, this fold is capable of creating many more shapes than we imagined.”

Think surgical stents that can be packed flat and pop-up into three-dimensional structures once inside the body or dining room tables that can lean flat against the wall until they are ready to be used.

“The collapsibility, transportability and deployability of Miura-ori folded objects makes it a potentially attractive design for everything from space-bound payloads to small-space living to laparoscopic surgery and soft robotics,” said Dudte.

Here’s a .gif demonstrating the fold,

This spiral folds rigidly from flat pattern through the target surface and onto the flat-folded plane (Image courtesy of Mahadevan Lab) Harvard University

The news release offers some details about the research,

To explore the potential of the tessellation, the team developed an algorithm that can create certain shapes using the Miura-ori fold, repeated with small variations. Given the specifications of the target shape, the program lays out the folds needed to create the design, which can then be laser printed for folding.

The program takes into account several factors, including the stiffness of the folded material and the trade-off between the accuracy of the pattern and the effort associated with creating finer folds – an important characterization because, as of now, these shapes are all folded by hand.

“Essentially, we would like to be able to tailor any shape by using an appropriate folding pattern,” said Mahadevan. “Starting with the basic mountain-valley fold, our algorithm determines how to vary it by gently tweaking it from one location to the other to make a vase, a hat, a saddle, or to stitch them together to make more and more complex structures.”

“This is a step in the direction of being able to solve the inverse problem – given a functional shape, how can we design the folds on a sheet to achieve it,” Dudte said.

“The really exciting thing about this fold is it is completely scalable,” said Mahadevan. “You can do this with graphene, which is one atom thick, or you can do it on the architectural scale.”

Co-authors on the study include Etienne Vouga, currently at the University of Texas at Austin, and Tomohiro Tachi from the University of Tokyo. …

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Programming curvature using origami tessellations by Levi H. Dudte, Etienne Vouga, Tomohiro Tachi, & L. Mahadevan. Nature Materials (2016) doi:10.1038/nmat4540 Published online 25 January 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.

Plastic memristors for neural networks

There is a very nice explanation of memristors and computing systems from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT). First their announcement, from a Jan. 27, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

A group of scientists has created a neural network based on polymeric memristors — devices that can potentially be used to build fundamentally new computers. These developments will primarily help in creating technologies for machine vision, hearing, and other machine sensory systems, and also for intelligent control systems in various fields of applications, including autonomous robots.

The authors of the new study focused on a promising area in the field of memristive neural networks – polymer-based memristors – and discovered that creating even the simplest perceptron is not that easy. In fact, it is so difficult that up until the publication of their paper in the journal Organic Electronics, there were no reports of any successful experiments (using organic materials). The experiments conducted at the Nano-, Bio-, Information and Cognitive Sciences and Technologies (NBIC) centre at the Kurchatov Institute by a joint team of Russian and Italian scientists demonstrated that it is possible to create very simple polyaniline-based neural networks. Furthermore, these networks are able to learn and perform specified logical operations.

A Jan. 27, 2016 MIPT press release on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, offers an explanation of memristors and a description of the research,

A memristor is an electric element similar to a conventional resistor. The difference between a memristor and a traditional element is that the electric resistance in a memristor is dependent on the charge passing through it, therefore it constantly changes its properties under the influence of an external signal: a memristor has a memory and at the same time is also able to change data encoded by its resistance state! In this sense, a memristor is similar to a synapse – a connection between two neurons in the brain that is able, with a high level of plasticity, to modify the efficiency of signal transmission between neurons under the influence of the transmission itself. A memristor enables scientists to build a “true” neural network, and the physical properties of memristors mean that at the very minimum they can be made as small as conventional chips.

Some estimates indicate that the size of a memristor can be reduced up to ten nanometers, and the technologies used in the manufacture of the experimental prototypes could, in theory, be scaled up to the level of mass production. However, as this is “in theory”, it does not mean that chips of a fundamentally new structure with neural networks will be available on the market any time soon, even in the next five years.

The plastic polyaniline was not chosen by chance. Previous studies demonstrated that it can be used to create individual memristors, so the scientists did not have to go through many different materials. Using a polyaniline solution, a glass substrate, and chromium electrodes, they created a prototype with dimensions that, at present, are much larger than those typically used in conventional microelectronics: the strip of the structure was approximately one millimeter wide (they decided to avoid miniaturization for the moment). All of the memristors were tested for their electrical characteristics: it was found that the current-voltage characteristic of the devices is in fact non-linear, which is in line with expectations. The memristors were then connected to a single neuromorphic network.

A current-voltage characteristic (or IV curve) is a graph where the horizontal axis represents voltage and the vertical axis the current. In conventional resistance, the IV curve is a straight line; in strict accordance with Ohm’s Law, current is proportional to voltage. For a memristor, however, it is not just the voltage that is important, but the change in voltage: if you begin to gradually increase the voltage supplied to the memristor, it will increase the current passing through it not in a linear fashion, but with a sharp bend in the graph and at a certain point its resistance will fall sharply.

Then if you begin to reduce the voltage, the memristor will remain in its conducting state for some time, after which it will change its properties rather sharply again to decrease its conductivity. Experimental samples with a voltage increase of 0.5V hardly allowed any current to pass through (around a few tenths of a microamp), but when the voltage was reduced by the same amount, the ammeter registered a figure of 5 microamps. Microamps are of course very small units, but in this case it is the contrast that is most significant: 0.1 μA to 5 μA is a difference of fifty times! This is more than enough to make a clear distinction between the two signals.

After checking the basic properties of individual memristors, the physicists conducted experiments to train the neural network. The training (it is a generally accepted term and is therefore written without inverted commas) involves applying electric pulses at random to the inputs of a perceptron. If a certain combination of electric pulses is applied to the inputs of a perceptron (e.g. a logic one and a logic zero at two inputs) and the perceptron gives the wrong answer, a special correcting pulse is applied to it, and after a certain number of repetitions all the internal parameters of the device (namely memristive resistance) reconfigure themselves, i.e. they are “trained” to give the correct answer.

The scientists demonstrated that after about a dozen attempts their new memristive network is capable of performing NAND logical operations, and then it is also able to learn to perform NOR operations. Since it is an operator or a conventional computer that is used to check for the correct answer, this method is called the supervised learning method.

Needless to say, an elementary perceptron of macroscopic dimensions with a characteristic reaction time of tenths or hundredths of a second is not an element that is ready for commercial production. However, as the researchers themselves note, their creation was made using inexpensive materials, and the reaction time will decrease as the size decreases: the first prototype was intentionally enlarged to make the work easier; it is physically possible to manufacture more compact chips. In addition, polyaniline can be used in attempts to make a three-dimensional structure by placing the memristors on top of one another in a multi-tiered structure (e.g. in the form of random intersections of thin polymer fibers), whereas modern silicon microelectronic systems, due to a number of technological limitations, are two-dimensional. The transition to the third dimension would potentially offer many new opportunities.

The press release goes to explain what the researchers mean when they mention a fundamentally different computer,

The common classification of computers is based either on their casing (desktop/laptop/tablet), or on the type of operating system used (Windows/MacOS/Linux). However, this is only a very simple classification from a user perspective, whereas specialists normally use an entirely different approach – an approach that is based on the principle of organizing computer operations. The computers that we are used to, whether they be tablets, desktop computers, or even on-board computers on spacecraft, are all devices with von Neumann architecture; without going into too much detail, they are devices based on independent processors, random access memory (RAM), and read only memory (ROM).

The memory stores the code of a program that is to be executed. A program is a set of instructions that command certain operations to be performed with data. Data are also stored in the memory* and are retrieved from it (and also written to it) in accordance with the program; the program’s instructions are performed by the processor. There may be several processors, they can work in parallel, data can be stored in a variety of ways – but there is always a fundamental division between the processor and the memory. Even if the computer is integrated into one single chip, it will still have separate elements for processing information and separate units for storing data. At present, all modern microelectronic systems are based on this particular principle and this is partly the reason why most people are not even aware that there may be other types of computer systems – without processors and memory.

*) if physically different elements are used to store data and store a program, the computer is said to be built using Harvard architecture. This method is used in certain microcontrollers, and in small specialized computing devices. The chip that controls the function of a refrigerator, lift, or car engine (in all these cases a “conventional” computer would be redundant) is a microcontroller. However, neither Harvard, nor von Neumann architectures allow the processing and storage of information to be combined into a single element of a computer system.

However, such systems do exist. Furthermore, if you look at the brain itself as a computer system (this is purely hypothetical at the moment: it is not yet known whether the function of the brain is reducible to computations), then you will see that it is not at all built like a computer with von Neumann architecture. Neural networks do not have a specialized computer or separate memory cells. Information is stored and processed in each and every neuron, one element of the computer system, and the human brain has approximately 100 billion of these elements. In addition, almost all of them are able to work in parallel (simultaneously), which is why the brain is able to process information with great efficiency and at such high speed. Artificial neural networks that are currently implemented on von Neumann computers only emulate these processes: emulation, i.e. step by step imitation of functions inevitably leads to a decrease in speed and an increase in energy consumption. In many cases this is not so critical, but in certain cases it can be.

Devices that do not simply imitate the function of neural networks, but are fundamentally the same could be used for a variety of tasks. Most importantly, neural networks are capable of pattern recognition; they are used as a basis for recognising handwritten text for example, or signature verification. When a certain pattern needs to be recognised and classified, such as a sound, an image, or characteristic changes on a graph, neural networks are actively used and it is in these fields where gaining an advantage in terms of speed and energy consumption is critical. In a control system for an autonomous flying robot every milliwatt-hour and every millisecond counts, just in the same way that a real-time system to process data from a collider detector cannot take too long to “think” about highlighting particle tracks that may be of interest to scientists from among a large number of other recorded events.

Bravo to the writer!

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Hardware elementary perceptron based on polyaniline memristive devices by V.A. Demin. V. V. Erokhin, A.V. Emelyanov, S. Battistoni, G. Baldi, S. Iannotta, P.K. Kashkarov, M.V. Kovalchuk. Organic Electronics Volume 25, October 2015, Pages 16–20 doi:10.1016/j.orgel.2015.06.015

This paper is behind a paywall.

Cities, technology, and some Vancouver (Canada) conversations

National Research Council of Canada

The National Research Council of Canada (NRC or sometimes NRCC) has started a new series of public engagement exercises based on the results from their last such project (Game changing technologies initiative) mentioned in my Jan. 30, 2015 posting. The report from that project ‘Summary of On-Line Dialogue with Stakeholders, February 9 – 27, 2015‘ has been released (from the summary’s overview),

Approximately 3000 invitations were sent out by NRC and collaborating organizations, including industry associations and other governmental organizations, to participate in a web-based, interactive dialogue. Participants were also welcomed to forward the invitation to members of their organization and their networks. In this early stage of NRC’s Game-Changing Technologies Initiative, emphasis was placed on selecting a diverse range of participants to ensure a wide breath of ideas and exchange. Once a few technology opportunities have been narrowed down by NRC, targeted consultation will take place for in-depth exploration.

Overall, 705 people registered on the web-based platform, with 261 active respondents (23% from industry; 22% from academia; 35% from government that included 26% from the Government of Canada; and 20% from the other category that included non-governmental organizations, interest groups, etc.). Sectors represented by the active participants included education, agriculture, management consulting, healthcare, research technology organizations, information and communications technologies, manufacturing, biotechnology, computer and electronics, aerospace, construction, finance, pharma and medicine, and public administration. Figure 1 outlines the distribution of active participants across Canada.

Once registered, participants were invited to review and provide input on up to seven opportunity areas:

• The cities of the future

• Prosperous and sustainable rural and remote communities

• Maintaining quality of life for an aging population

• Protecting Canadian security and privacy

• Transforming the classroom for continuous and adaptive learning

• Next generation health care systems

• A safe, sustainable and profitable food industry (p. 4 of the PDF summary)

Here’s the invitation to participate in the ‘cities’ discussion (from a Jan. 22, 2016 email invite),

I would like to invite you to participate in the next phase of NRC’s Game-Changing Technologies Initiative, focused on the Cities of the Future. Participation will take place via an interactive on-line tool allowing participants to provide insights and to engage in exchanges with each other. The on-line tool is available at https://facpro.intersol.ca (User ID: Cities, Password: NRC) starting today and continuing until February 8, 2016. Input from stakeholders like you is critical to helping NRC identify game-changing technologies with the potential to improve Canada’s future competitiveness, productivity and quality of life.

In 2014, NRC began working with stakeholders to identify technology areas that have the potential for revolutionary impacts on Canadian prosperity and the lives of Canadians over the next 20 to 30 years. Through this process, we identified seven opportunities critical to Canada’s future, which were submitted for comments to a diverse range of thought-leaders from different backgrounds across Canada in February 2015. A summary of comments received is available at http://www.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/obj/doc/game_changing-revolutionnaires/game_changing_technologies_initiative_summary_of_dialogue.pdf (PDF, 3.71 MB).

We then selected The Cities of the Future as the first area for in-depth exploration with stakeholders and potential partners. The online exercise will focus on the challenges that Canadian cities will face in the coming decades, with the goal of selecting specific problems that have the potential for national R&D partnerships and disruptive socio-economic impacts for Canada. The outcomes of this exercise will be discussed at a national event (by invitation only) to take place in early 2016.

Please feel free to forward this invitation to members of your organization or your expert network who may also want to contribute. Should you or a member of your team have any questions about this initiative, please do not hesitate to contact Dr. Carl Caron at: Carl.Caron@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca … .

Before you rush off to participate, you might like to know how the participants’ dialogue was summarized (from the report),

The Opportunity: Urban areas are struggling to manage traffic congestion, provision of basic utilities, waste disposal, air quality and more. These issues will grow as more and more people migrate to large cities. Future technologies – such as connected vehicles, delivery drones, waste-to-energy systems, and self-repairing materials could enable sustainable, urban growth for Canada and the world.

Participant Response: Many participants pointed out that most of the technologies described in the opportunity area already exist/are under development. What is needed is pricing and performance improvements to increase scalability and market penetration. Participants that neither agreed nor disagreed stated that replacing aging infrastructure and high costs would be major stumbling blocks. It was suggestedthat the focus should be on a shift to smaller, interconnectedsatellite communities capable of scalable energy production and distribution,local food production, waste management, and recreational space. (p. 6)

Cities rising in important as political entities

There’s a notion that cities as they continue growing will become the most important governance structure in most people’s lives and judging from the NRC’s list, it would seem that organization recognizes the rising importance of cities, if not their future dominance.

Parag Khanna wrote a February 2011 essay (When cities rule the world) for McKinsey & Company making the argument for city dominance in the future. For anyone not familiar with Khanna (from his eponymous website),

Parag Khanna is a leading global strategist, world traveler, and best-selling author. He is a CNN Global Contributor and Senior Research Fellow in the Centre on Asia and Globalisation at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. He is also the Managing Partner of Hybrid Reality, a boutique geostrategic advisory firm, and Co-Founder & CEO of Factotum, a leading content branding agency.

Given that Singapore is a city and a state, Khanna would seem uniquely placed to comment on the possibilities. Here are a few comments from Khanna’s essay,

…

The 21st century will not be dominated by America or China, Brazil or India, but by The City. In a world that increasingly appears ungovernable, cities—not states—are the islands of governance on which the future world order will be built. Cities are humanity’s real building blocks because of their economic size, population density, political dominance, and innovative edge. They are real “facts on the ground,” almost immeasurably more meaningful to most people in the world than often invisible national borders.

In this century, it will be the city—not the state—that becomes the nexus of economic and political power. Already, the world’s most important cities generate their own wealth and shape national politics as much as the reverse. The rise of global hubs in Asia is a much more important factor in the rebalancing of global power between West and East than the growth of Asian military power, which has been much slower. In terms of economic might, consider that just forty city-regions are responsible for over two-thirds of the total world economy and most of its innovation. To fuel further growth, an estimated $53 trillion will be invested in urban infrastructure in the coming two decades.

Vancouver conversations (cities and mass migrations)

On a somewhat related note (i.e., ‘global cities’ and the future), there’s going to be talk in Vancouver about ‘mass migrations’ and their impact on cities. From the Dante Society of British Columbia events page,

The Dante Alighieri Society of BC and ARPICO and are pleased to invite you to a public lecture “Global Nomads, Modern Caravanserais and Neighbourhood Commons” which will take place on January 27th at 7.00 pm at the Vancouver Public Library.

Please see details below.

———————————————————————-

Global Nomads, Modern Caravanserais and Neighbourhood Commons

Dr. Arianna Dagnino

Wednesday, January 27, 2016, 7.00 pm

Vancouver Public Library, Alma VanDusen Room, 350 W Georgia St., Vancouver BC V6B 6B1

—————————————————————————Global cities such as Vancouver, London, Berlin or Sydney currently face two major challenges: housing affordability and the risk of highly fragmented societies along cultural lines.

In her talk “Global Nomads, Modern Caravanserais and Neighbourhood Commons” Dr. Dagnino argues that one of the possible solutions to address the negative aspects of economic globalization and the disruptive effects of mass-migrations is to envisage a new kind of housing complex, “the transcultural caravanserai.”

The caravanserai in itself is not a new concept: in late antiquity until the advent of the railway, this kind of structure functioned to lodge nomads along the caravan routes in the desert regions of Asia or North Africa and allowed people on the move to meet and interact with members of sedentary communities.

Dr. Dagnino re-visits the socio-cultural function of the caravanserai showing its potential as a polyfunctional hub of mutual hospitality and creative productivity. She also gives account of how contemporary architects and designers have already started to re-envisage the role of the caravanserai for the global city of the future not only as a transcultural “third space” that courageously cuts across ethnicities, cultures, and religions but also as a model for low-rise, high density urban complex. This model contemplates a mix of residential units, commercial and trades activities, craftsman workshops, arts studios, educational enterprises, and public spaces for active fruition, thus reinstating the productive use of property and the residents’ engagement with the Commons.

—————————————————————————

Dr. Arianna Dagnino is an Italian researcher, writer, and socio-cultural analyst. She holds an M.A. in Modern Foreign Languages and Literatures from l’Università degli Studi di Genova and a Ph.D. in Sociology and Comparative Literature from the University of South Australia. She currently teaches at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, where she is conducting research in the field of transcultural studies. She is a Board Member of the newly-established Dante Alighieri Society of British Columbia (www.dantesocietybc.ca).

Dr. Dagnino research interest focuses on how socio-economic factors and cultural changes linked to global mobility shape identities, interpersonal relations, cultural practices, and urban environments. As an international journalist and scholar, Dr. Dagnino has travelled across and lived in various parts of the globe. Her neonomadic routes have led her to study Russian in Gorbachev’s Moscow, investigate the researchers’ quest for ground-breaking technologies at MIT in Boston, witness the momentous change of regime in South Africa, analyze the effects of multiculturalism in Australia, and examine the progressive Asianization of Western Canada. In her twenty-year long activity Dr. Dagnino has published several books on the socio-cultural impact of globalization, transnational flows, and digital technologies. Among them, I Nuovi Nomadi (New Nomads; Castelvecchi, 1996), Uoma (Woman-Machine, Mursia, 2000), and Jesus Christ Cyberstar (IPOC, 2009 [2002]). Dr. Dagnino is also the author of a transcultural novel, Fossili (Fossils, Fazi Editore, 2010), inspired by her four years spent in sub-Saharan Africa, and of the recently published book Transcultural Authors and Novels in the Age of Global Mobility (Purdue University Press, 2015).

—————————————————————————Please join us for a presentation & lively discussion.

Date & Time: [Wednesday] January 27, 2016, 7.00 pm. Doors open at 6.45 pm.

Location: Vancouver Public Library, Alma VanDusen Room, 350 W Georgia St., Vancouver BC V6B 6B1

Parking is available underground in the library building with entrance on Hamilton Street near Robson until midnight.Refreshments: Complimentary following the event

Admission: Free

RSVP: Registration is highly recommended as seating is limited. Please register at info@arpico.ca by January 25, 2016, or at Event Brite: Link to the event: https://goo.gl/phAxTwWe look forward to seeing you at the event.

Best Regards,

ARPICO – Society of Italian Researchers and Professionals in Western Canada

and The Dante Society of BC

Tickets are still available as of Jan. 27, 2016 at 1015 hours PST but you might want to hurry if you’re planning to register. *ETA Jan. 27, 2016 1150 hours PST, they are now putting people on a wait list.*

Vancouver conversations (Creating the New Vancouver)

There has been a great deal of discussion and controversy as Vancouverites become concerned over affordability and livability issues. The current political party ruling the City Council almost lost its majority position in a November 2014 election due to the controversial nature of the changes encouraged by the ruling party. The City Manager, Penny Ballem, was effectively fired September 2015 in what many saw as a response to the ongoing criticism over development issues. A few months later (November 2015) , the City’s chief planner abruptly retired. And, there’s more. (For the curious, you can start with Daniel Wood and his story on development plans on Vancouver’s downtown waterfront (Nov. 25, 2015 article for the Georgia Straight. You can also check out various stories on Bob Mackin’s website. Mackin is a local Vancouver journalist who closely follows the local political scene. There’s also Jeff Lee who writes for the Vancouver Sun newspaper and its ‘Civic Lee Speaking‘ blog but he does have a number of local human interest stories mixed in with his political pieces.)

Getting to the point: in the midst of all this activity and controversy, the Museum of Vancouver has opened a new exhibit, Your Future Home: Creating the New Vancouver,

From the Vancouver Urbanarium Society and the Museum of Vancouver comes the immersive and timely new exhibition, Your Future Home: Creating the New Vancouver.

As it explores the hottest topics in Vancouver today—housing affordability, urban density, mobility, and public space—Your Future Home invites people to discover surprising facts about the city and imagine what Vancouver might become. This major exhibition engages visitors with the bold visual language and lingo of real estate advertising as it presents the visions of talented Vancouver designers about how we might design the cityscapes of the future. Throughout the run of the exhibition, visitors can deepen their experience through a series of programs, including workshops, happy hours, and debates among architectural, real estate and urban planning experts.

Events & Programs

Vancouver Debates I – Wednesday, January 20 [2016]

How and where will Vancouver and its region accommodate increased population? In densifying neighborhoods, where do issues of fairness, democracy, ecology and community preservation come into play? Should any areas be off limits? Hosted by Urbanarium. Featuring Joyce Drohan (pro), Brent Toderian (pro), Sam Sullivan (con), Michael Goldberg (con).Built City Speaker Series II – Thursday, February 11 [2016]

The world’s industrial design processes are becoming more precise, more computerized and more perfect. In contrast, buildings are still hand-made, imperfect and almost crude. D’Arcy Jones will present recent studio work, highlighting their successes and failures in the pursuit of craft within the limits of contemporary construction. Visual artist, Germaine Koh’s public interventions and urban situations cultivate an active citizenry through play and conceptual provocation. She will present Home Made Home, her project for building small dwellings, which promotes DIY community building and creative strategies for occupying urban space. More Info.

Talk & Tours

Intimate conversations with designers, architects and curators during tours of the exhibition.Happy Hours

The most edutaining night of the week. Have a drink, watch a presentation. MOV combines learning with a fun, tsocial experience.Out & About Walking Tours

Explorations of Vancouver architecture and infrastructure, led by urban experts.Design Sundays Group Workshops

A series of workshops in April [2016] discussing the exhibition’s themes of housing affordability, urban density, mobility, and public space.

Interestingly and strangely, there’s no mention or discussion in the exhibit plans of the impact technology and science may have on Vancouver’s future even though the metropolitan area is abuzz with various science and technology startups and has two universities (University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University) with considerable investment in science and technology studies.

Finally, it seems no matter where you live, the topic of ‘cities’ and their roles in our collective futures is of urgent interest.

4D printing: a hydrogel orchid

In 2013, the 4th dimension for printing was self-assembly according to a March 1, 2013 article by Tuan Nguyen for ZDNET. A Jan. 25, 2016 Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University news release (also on EurekAlert) points to time as the fourth dimension in a description of the Wyss Institute’s latest 4D printed object,

A team of scientists at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences has evolved their microscale 3D printing technology to the fourth dimension, time. Inspired by natural structures like plants, which respond and change their form over time according to environmental stimuli, the team has unveiled 4D-printed hydrogel composite structures that change shape upon immersion in water.

“This work represents an elegant advance in programmable materials assembly, made possible by a multidisciplinary approach,” said Jennifer Lewis, Sc.D., senior author on the new study. “We have now gone beyond integrating form and function to create transformable architectures.”

…

In nature, flowers and plants have tissue composition and microstructures that result in dynamic morphologies that change according to their environments. Mimicking the variety of shape changes undergone by plant organs such as tendrils, leaves, and flowers in response to environmental stimuli like humidity and/or temperature, the 4D-printed hydrogel composites developed by Lewis and her team are programmed to contain precise, localized swelling behaviors. Importantly, the hydrogel composites contain cellulose fibrils that are derived from wood and are similar to the microstructures that enable shape changes in plants.

…

By aligning cellulose fibrils (also known as, cellulose nanofibrils or nanofibrillated cellulose) during printing, the hydrogel composite ink is encoded with anisotropic swelling and stiffness, which can be patterned to produce intricate shape changes. The anisotropic nature of the cellulose fibrils gives rise to varied directional properties that can be predicted and controlled. Just like wood, which can be split easier along the grain rather than across it. Likewise, when immersed in water, the hydrogel-cellulose fibril ink undergoes differential swelling behavior along and orthogonal to the printing path. Combined with a proprietary mathematical model developed by the team that predicts how a 4D object must be printed to achieve prescribed transformable shapes, the new method opens up many new and exciting potential applications for 4D printing technology including smart textiles, soft electronics, biomedical devices, and tissue engineering.

“Using one composite ink printed in a single step, we can achieve shape-changing hydrogel geometries containing more complexity than any other technique, and we can do so simply by modifying the print path,” said Gladman [A. Sydney Gladman, Wyss Institute a graduate research assistant]. “What’s more, we can interchange different materials to tune for properties such as conductivity or biocompatibility.”

The composite ink that the team uses flows like liquid through the printhead, yet rapidly solidifies once printed. A variety of hydrogel materials can be used interchangeably resulting in different stimuli-responsive behavior, while the cellulose fibrils can be replaced with other anisotropic fillers of choice, including conductive fillers.

“Our mathematical model prescribes the printing pathways required to achieve the desired shape-transforming response,” said Matsumoto [Elisabetta Matsumoto, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at the Wyss]. “We can control the curvature both discretely and continuously using our entirely tunable and programmable method.”

Specifically, the mathematical modeling solves the “inverse problem”, which is the challenge of being able to predict what the printing toolpath must be in order to encode swelling behaviors toward achieving a specific desired target shape.

“It is wonderful to be able to design and realize, in an engineered structure, some of nature’s solutions,” said Mahadevan [L. Mahadevan, Ph.D., a Wyss Core Faculty member] , who has studied phenomena such as how botanical tendrils coil, how flowers bloom, and how pine cones open and close. “By solving the inverse problem, we are now able to reverse-engineer the problem and determine how to vary local inhomogeneity, i.e. the spacing between the printed ink filaments, and the anisotropy, i.e. the direction of these filaments, to control the spatiotemporal response of these shapeshifting sheets. ”

“What’s remarkable about this 4D printing advance made by Jennifer and her team is that it enables the design of almost any arbitrary, transformable shape from a wide range of available materials with different properties and potential applications, truly establishing a new platform for printing self-assembling, dynamic microscale structures that could be applied to a broad range of industrial and medical applications,” said Wyss Institute Founding Director Donald Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children’s Hospital and Professor of Bioengineering at Harvard SEAS [School of Engineering and Applied Science’.

Here’s an animation from the Wyss Institute illustrating the process,

And, here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Biomimetic 4D printing by A. Sydney Gladman, Elisabetta A. Matsumoto, Ralph G. Nuzzo, L. Mahadevan, & Jennifer A. Lewis. Nature Materials (2016) doi:10.1038/nmat4544 Published online 25 January 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.