This was going to be written for January 2020 but sometimes things happen (e.g., a two-part overview of science culture in Canada from 2010-19 morphed into five parts with an addendum and, then, a pandemic). By now (July 28, 2020), Dr. He’s sentencing to three years in jail announced by the Chinese government in January 2020 is old news.

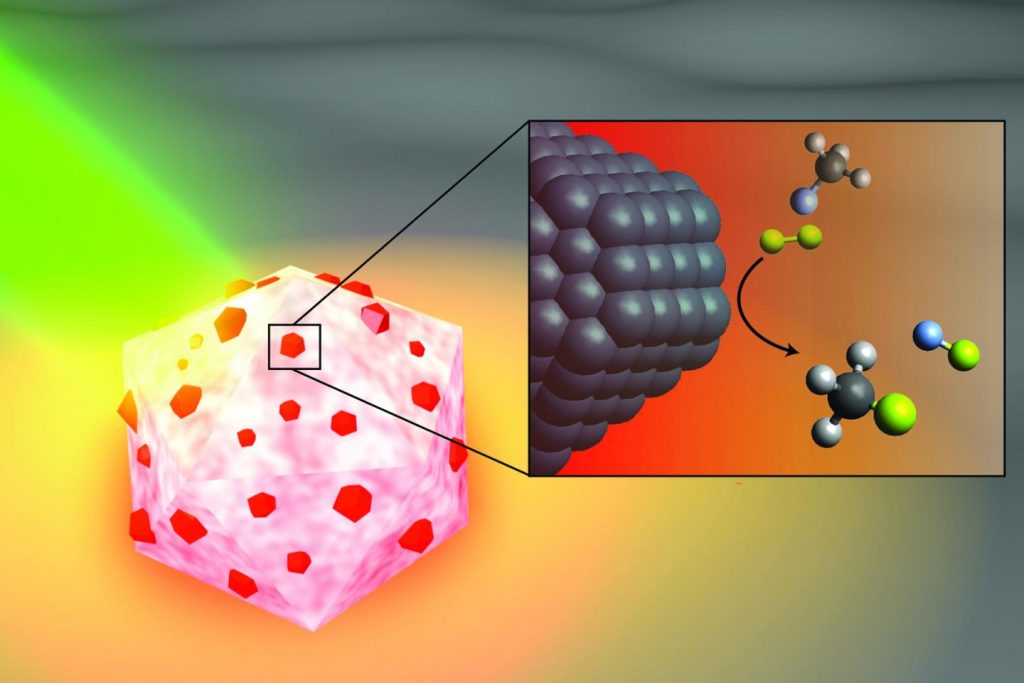

Regardless, it seems a neat and tidy ending to an international scientific scandal concerned with germline-editing which resulted in at least one set of twins, Lulu and Nana. He claimed to have introduced a variant (“Delta 32” variation) of their CCR5 gene. This does occur naturally and scientists have noted that people with this mutation seem to be resistant to HIV and smallpox.

For those not familiar with the events surrounding the announcement, here’s a brief recap. News of the world’s first gene-edited twins’ birth was announced in November 2018 just days before an international meeting group of experts who had agreed on a moratorium in 2015 on exactly that kind of work. The scientist making the announcement about the twins was scheduled for at least one presentation at the meeting, which was to be held in Hong Kong. He did give his presentation but left the meeting shortly afterwards as shock was beginning to abate and fierce criticism was rising. My November 28, 2018 posting (First CRISPR gene-edited babies? Ethics and the science story) offers a timeline of sorts and my initial response.

I subsequently followed up with two mores posts as the story continued to develop. My May 17, 2019 posting (Genes, intelligence, Chinese CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) babies, and other children) featured news that Dr. He’s gene-editing may have resulted in the twins having improved cognitive skills. Then, more news broke. The title for my June 20, 2019 posting (Greater mortality for the CRISPR twins Lulu and Nana?) is self-explanatory.

I have roughly organized my sources for this posting into two narratives, which I’m contrasting with each other. First, there is one found in the mainstream media (English language), ‘The Popular Narrative’. Second, there is story where Dr. He is viewed more sympathetically and as part of a larger community where there isn’t nearly as much consensus over what should or shouldn’t be done as ‘the popular narrative’ insists.

The popular narrative: Dr. He was a rogue scientist

A December 30, 2019 article for Fast Company by Kristin Toussaint lays out the latest facts (Note: A link has been removed),

… Now, a court in China has sentenced He to three years in prison, according to Xinhua, China’s state-run press agency, for “illegal medical practices.”

The court in China’s southern city of Shenzhen says that He’s team, which included colleagues Zhang Renli and Qin Jinzhou from two medical institutes in Guangdong Province, falsified ethical approval documents and violated China’s “regulations and ethical principles” with their gene-editing work. Zhang was sentenced to two years in jail, and Qin to 18 months with a two-year reprieve, according to Xinhau.

…

Ian Sample’s December 31, 2020 article for the Guardian offers more detail (Note: Links have been removed),

…

The court in Shenzhen found He guilty of “illegal medical practices” and in addition to the prison sentence fined him 3m yuan (£327,360), according to the state news agency, Xinhua. Two others on He’s research team received lesser fines and sentences.

“The three accused did not have the proper certification to practise medicine, and in seeking fame and wealth, deliberately violated national regulations in scientific research and medical treatment,” the court said, according to Xinhua. “They’ve crossed the bottom line of ethics in scientific research and medical ethics.”

…

[…] the court found He had forged documents from an ethics review panel that were used to recruit couples for the research. The couples that enrolled had a man with HIV and a woman without and were offered IVF in return for taking part.

Zhang Renli, who worked with He, was sentenced to two years in prison and fined 1m yuan. Colleague Qin Jinzhou received an 18-month sentence, but with a two-year reprieve, and a 500,000 yuan fine.

He’s experiments, which were carried out on seven embryos in late 2018, sent shockwaves through the medical and scientific world. The work was swiftly condemned for deceiving vulnerable patients and using a risky, untested procedure with no medical justification. Earlier this month, MIT Technology Review released excerpts from an early manuscript of He’s work. It casts serious doubts on his claims to have made the children immune to HIV.

…

Even as the scientific community turned against He, the scientist defended his work and said he was proud of having created Lulu and Nana. A third child has since been born as a result of the experiments.

Robin Lovell-Badge at the Francis Crick Institute in London said it was “far too premature” for anyone to pursue genome editing on embryos that are intended to lead to pregnancies. “At this stage we do not know if the methods will ever be sufficiently safe and efficient, although the relevant science is progressing rapidly, and new methods can look promising. It is also important to have standards established, including detailed regulatory pathways, and appropriate means of governance.”

…

A December 30, 2019 article, by Carolyn Y. Johnson for the Washington Post, covers much the same ground although it does go on to suggest that there might be some blame to spread around (Note: Links have been removed),

The Chinese researcher who stunned and alarmed the international scientific community with the announcement that he had created the world’s first gene-edited babies has been sentenced to three years in prison by a court in China.

He Jiankui sparked a bioethical crisis last year when he claimed to have edited the DNA of human embryos, resulting in the birth of twins called Lulu and Nana as well as a possible third pregnancy. The gene editing, which was aimed at making the children immune to HIV, was excoriated by many scientists as a reckless experiment on human subjects that violated basic ethical principles.

…

The judicial proceedings were not public, and outside experts said it is hard to know what to make of the punishment without the release of the full investigative report or extensive knowledge of Chinese law and the conditions under which He will be incarcerated.

Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California at Berkeley who co-invented CRISPR, the gene editing technology that He utilized, has been outspoken in condemning the experiments and has repeatedly said CRISPR is not ready to be used for reproductive purposes.

…

R. Alta Charo, a fellow at Stanford’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, was among a small group of experts who had dinner with He the night before he unveiled his controversial research in Hong Kong in November 2018.

“He Jiankui is an example of somebody who fundamentally didn’t understand, or didn’t want to recognize, what have become international norms around responsible research,” Charo said. “My impression is he allowed his personal ambition to completely cloud rational thinking and judgment.”

…

Scientists have been testing an array of powerful biotechnology tools to fix genetic diseases in adults. There is tremendous excitement about the possibility of fixing genes that cause serious disease, and the first U.S. patients were treated with CRISPR this year.

But scientists have long drawn a clear moral line between curing genetic diseases in adults and editing and implanting human embryos, which raises the specter of “designer babies.” Those changes and any unanticipated ones could be inherited by future generations — in essence altering the human species.

…

“The fact that the individual at the center of the story has been punished for his role in it should not distract us from examining what supporting roles were played by others, particularly in the international scientific community and also the environment that shaped and encouraged him to push the limits,” said Benjamin Hurlbut [emphasis mine], associate professor in the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University.

Stanford University cleared its scientists, including He’s former postdoctoral adviser, Stephen Quake, finding that Quake and others did not participate in the research and had expressed “serious concerns to Dr. He about his work.” A Rice University spokesman said an investigation continues into bioengineering professor Michael Deem, He’s former academic adviser. Deem was listed as a co-author on a paper called “Birth of Twins After Genome Editing for HIV Resistance,” submitted to scientific journals, according to MIT Technology Review.

It’s interesting that it’s only the Chinese scientists who are seen to be punished, symbolically at least. Meanwhile, Stanford clears its scientists of any wrongdoing and Rice University continues to investigate.

Watch for the Hurlbut name (son, Benjamin and father, William) to come up again in the ‘complex narrative’ section.

Criticism of the ‘twins’ CRISPR editing’ research

Antonio Regalado’s December 3, 2020 article for the MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Technology Review features comments from various experts on an unpublished draft of Dr. He Jiankui’s research

Earlier this year a source sent us a copy of an unpublished manuscript describing the creation of the first gene-edited babies, born last year in China. Today, we are making excerpts of that manuscript public for the first time.

Titled “Birth of Twins After Genome Editing for HIV Resistance,” and 4,699 words long, the still unpublished paper was authored by He Jiankui, the Chinese biophysicist who created the edited twin girls. A second manuscript we also received discusses laboratory research on human and animal embryos.

The metadata in the files we were sent indicate that the two draft papers were edited by He in late November 2018 and appear to be what he initially submitted for publication. Other versions, including a combined manuscript, may also exist. After consideration by at least two prestigious journals, Nature and JAMA, his research remains unpublished.

The text of the twins paper is replete with expansive claims of a medical breakthrough that can “control the HIV epidemic.” It claims “success”—a word used more than once—in using a “novel therapy” to render the girls resistant to HIV. Yet surprisingly, it makes little attempt to prove that the twins really are resistant to the virus. And the text largely ignores data elsewhere in the paper suggesting that the editing went wrong.

We shared the unpublished manuscripts with four experts—a legal scholar, an IVF doctor, an embryologist, and a gene-editing specialist—and asked them for their reactions. Their views were damning. Among them: key claims that He and his team made are not supported by the data; the babies’ parents may have been under pressure to agree to join the experiment; the supposed medical benefits are dubious at best; and the researchers moved forward with creating living human beings before they fully understood the effects of the edits they had made.

…

1. Why aren’t the doctors among the paper’s authors?

The manuscript begins with a list of the authors—10 of them, mostly from He Jiankui’s lab at the Southern University of Science and Technology, but also including Hua Bai, director of an AIDS support network, who helped recruit couples, and Michael Deem, an American biophysicist whose role is under review by Rice University. (His attorney previously said Deem never agreed to submit the manuscript and sought to remove his name from it.)

It’s a small number of people for such a significant project, and one reason is that some names are missing—notably, the fertility doctors who treated the patients and the obstetrician who delivered the babies. Concealing them may be an attempt to obscure the identities of the patients. However, it also leaves unclear whether or not these doctors understood they were helping to create the first gene-edited babies.

To some, the question of whether the manuscript is trustworthy arises immediately.

—Hank Greely, professor of law, Stanford University: We have no, or almost no, independent evidence for anything reported in this paper. Although I believe that the babies probably were DNA-edited and were born, there’s very little evidence for that. Given the circumstances of this case, I am not willing to grant He Jiankui the usual presumption of honesty.

…

That last article by Regalado is the purest example I have of how fierce the criticism is and how almost all of it is focused on Dr. He and his Chinese colleagues.

A complex, measured narrative: multiple players in the game

The most sympathetic and, in many ways, the most comprehensive article is an August 1, 2019 piece by Jon Cohen for Science magazine (Note: Links have been removed),

On 10 June 2017, a sunny and hot Saturday in Shenzhen, China, two couples came to the Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech) to discuss whether they would participate in a medical experiment that no researcher had ever dared to conduct. The Chinese couples, who were having fertility problems, gathered around a conference table to meet with He Jiankui, a SUSTech biophysicist. Then 33, He (pronounced “HEH”) had a growing reputation in China as a scientist-entrepreneur but was little known outside the country. “We want to tell you some serious things that might be scary,” said He, who was trim from years of playing soccer and wore a gray collared shirt, his cuffs casually unbuttoned.

He simply meant the standard in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures. But as the discussion progressed, He and his postdoc walked the couples through informed consent forms [emphasis mine] that described what many ethicists and scientists view as a far more frightening proposition. Seventeen months later, the experiment triggered an international controversy, and the worldwide scientific community rejected him. The scandal cost him his university position and the leadership of a biotech company he founded. Commentaries labeled He, who also goes by the nickname JK, a “rogue,” “China’s Frankenstein,” and “stupendously immoral.” [emphases mine]

But that day in the conference room, He’s reputation remained untarnished. As the couples listened and flipped through the forms, occasionally asking questions, two witnesses—one American, the other Chinese—observed [emphasis mine]. Another lab member shot video, which Science has seen [emphasis mine], of part of the 50-minute meeting. He had recruited those couples because the husbands were living with HIV infections kept under control by antiviral drugs. The IVF procedure would use a reliable process called sperm washing to remove the virus before insemination, so father-to-child transmission was not a concern. Rather, He sought couples who had endured HIV-related stigma and discrimination and wanted to spare their children that fate by dramatically reducing their risk of ever becoming infected. [emphasis mine]

He, who for much of his brief career had specialized in sequencing DNA, offered a potential solution: CRISPR, the genome-editing tool that was revolutionizing biology, could alter a gene in IVF embryos to cripple production of an immune cell surface protein, CCR5, that HIV uses to establish an infection. “This technique may be able to produce an IVF baby naturally immunized against AIDS,” one consent form read.[emphasis mine]

The couples’ children could also pass the protective mutation to future generations. The prospect of this irrevocable genetic change is why, since the advent of CRISPR as a genome editor 5 years earlier, the editing of human embryos, eggs, or sperm has been hotly debated. The core issue is whether such germline editing would cross an ethical red line because it could ultimately alter our species. Regulations, some with squishy language, arguably prohibited it in many countries, China included.

Yet opposition was not unanimous. A few months before He met the couples, a committee convened by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) concluded in a well-publicized report that human trials of germline editing “might be permitted” if strict criteria were met. The group of scientists, lawyers, bioethicists, and patient advocates spelled out a regulatory framework but cautioned that “these criteria are necessarily vague” because various societies, caregivers, and patients would view them differently. The committee notably did not call for an international ban, arguing instead for governmental regulation as each country deemed appropriate and “voluntary self-regulation pursuant to professional guidelines.”

…

[…] He hid his plans and deceived his colleagues and superiors, as many people have asserted? A preliminary investigation in China stated that He had forged documents, “dodged supervision,” and misrepresented blood tests—even though no proof of those charges was released [emphasis mine], no outsiders were part of the inquiry, and He has not publicly admitted to any wrongdoing. (CRISPR scientists in China say the He fallout has affected their research.) Many scientists outside China also portrayed He as a rogue actor. “I think there has been a failure of self-regulation by the scientific community because of a lack of transparency,” virologist David Baltimore, a Nobel Prize–winning researcher at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena and co-chair of the Hong Kong summit, thundered at He after the biophysicist’s only public talk on the experiment.

Because the Chinese government has revealed little and He is not talking, key questions about his actions are hard to answer. Many of his colleagues and confidants also ignored Science‘s requests for interviews. But Ryan Ferrell, a public relations specialist He hired, has cataloged five dozen people who were not part of the study but knew or suspected what He was doing before it became public. Ferrell calls it He’s circle of trust. [emphasis mine]

That circle included leading scientists—among them a Nobel laureate—in China and the United States, business executives, an entrepreneur connected to venture capitalists, authors of the NASEM report, a controversial U.S. IVF specialist [John Zhang] who discussed opening a gene-editing clinic with He [emphasis mine], and at least one Chinese politician. “He had an awful lot of company to be called a ‘rogue,’” says geneticist George Church [emphases mine], a CRISPR pioneer at Harvard University who was not in the circle of trust and is one of the few scientists to defend at least some aspects of He’s experiment.

Some people sharply criticized He when he brought them into the circle; others appear to have welcomed his plans or did nothing. Several went out of their way to distance themselves from He after the furor erupted. For example, the two onlookers in that informed consent meeting were Michael Deem, He’s Ph.D. adviser at Rice University in Houston, Texas, and Yu Jun, a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and co-founder of the Beijing Genomics Institute, the famed DNA sequencing company in Shenzhen. Deem remains under investigation by Rice for his role in the experiment and would not speak with Science. In a carefully worded statement, Deem’s lawyers later said he “did not meet the parents of the reported CCR5-edited children, or anyone else whose embryos were edited.” But earlier, Deem cooperated with the Associated Press (AP) for its exclusive story revealing the birth of the babies, which reported that Deem was “present in China when potential participants gave their consent and that he ‘absolutely’ thinks they were able to understand the risks. [emphasis mine]”

Yu, who works at CAS’s Beijing Institute of Genomics, acknowledges attending the informed consent meeting with Deem, but he told Science he did not know that He planned to implant gene-edited embryos. “Deem and I were chatting about something else,” says Yu, who has sequenced the genomes of humans, rice, silkworms, and date palms. “What was happening in the room was not my business, and that’s my personality: If it’s not my business, I pay very little attention.”

Some people who know He and have spoken to Science contend it is time for a more open discussion of how the biophysicist formed his circle of confidants and how the larger circle of trust—the one between the scientific community and the public—broke down. Bioethicist William Hurlbut at Stanford University [emphasis mine] in Palo Alto, California, who knew He wanted to conduct the embryo-editing experiment and tried to dissuade him, says that He was “thrown under the bus” by many people who once supported him. “Everyone ran for the exits, in both the U.S. and China. I think everybody would do better if they would just openly admit what they knew and what they did, and then collectively say, ‘Well, people weren’t clear what to do. We should all admit this is an unfamiliar terrain.’”

…

Steve Lombardi, a former CEO of Helicos, reacted far more charitably. Lombardi, who runs a consulting business in Bridgewater, Connecticut, says Quake introduced him to He to help find investors for Direct Genomics. “He’s your classic, incredibly bright, naïve entrepreneur—I run into them all the time,” Lombardi says. “He had the right instincts for what to do in China and just didn’t know how to do it. So I put him in front of as many people as I could.” Lombardi says He told him about his embryo-editing ambitions in August 2017, asking whether Lombardi could find investors for a new company that focused on “genetic medical tourism” and was based in China or, because of a potentially friendlier regulatory climate, Thailand. “I kept saying to him, ‘You know, you’ve got to deal with the ethics of this and be really sure that you know what you’re doing.’”

…

In April 2018, He asked Ferrell to handle his media full time. Ferrell was a good fit—he had an undergraduate degree in neuroscience, had spent a year in Beijing studying Chinese, and had helped another company using a pre-CRISPR genome editor. Now that a woman in the trial was pregnant, Ferrell says, He’s “understanding of the gravity of what he had done increased.” Ferrell had misgivings about the experiment, but he quit HDMZ and that August moved to Shenzhen. With the pregnancy already underway, Ferrell reasoned, “It was going to be the biggest science story of that week or longer, no matter what I did.”

…

MIT Technology Review had broken a story early that morning China time, saying human embryos were being edited and implanted, after reporter Antonio Regalado discovered descriptions of the project that He had posted online, without Ferrell’s knowledge, in an official Chinese clinical trial registry. Now, He gave AP the green light to post a detailed account, which revealed that twin girls—whom He, to protect their identifies, named Lulu and Nana—had been born. Ferrell and He also posted five unfinished YouTube videos explaining and justifying the unprecedented experiment.

“He was fearful that he’d be unable to communicate to the press and the onslaught in a way that would be in any way manageable for him,” Ferrell says. One video tried to forestall eugenics accusations, with He rejecting goals such as enhancing intelligence, changing skin color, and increasing sports performance as “not love.” Still, the group knew it had lost control of the news. [emphasis mine]

…

… On 7 March 2017, 5 weeks after the California gathering, He submitted a medical ethics approval application to the Shenzhen HarMoniCare Women and Children’s Hospital that outlined the planned CCR5 edit of human embryos. The babies, it claimed, would be resistant to HIV as well as to smallpox and cholera. (The natural CCR5 mutation may have been selected for because it helps carriers survive smallpox and plague, some studies suggest—but they don’t mention cholera.) “This is going to be a great science and medicine achievement ever since the IVF technology which was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2010, and will also bring hope to numerous genetic disease patients,” the application says. Seven people on the ethics committee, chaired by Lin Zhitong—a one-time Direct Genomics director and a HarMoniCare administrator—signed the application, indicating they approved it.

…

[…] John Zhang, […] [emphasis mine] earned his medical degree in China and a Ph.D. in reproductive biology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. Zhang had made international headlines himself in September 2016, when New Scientist revealed that he had created the world’s first “three-parent baby” by using mitochondrial DNA from a donor egg to revitalize the egg of a woman with infertility and then inseminating the resulting egg. “This technology holds great hope for ladies with advanced maternal age to have their own children with their own eggs,” Zhang explains in the center’s promotional video, which alternates between Chinese and English. It does not mention that Zhang did the IVF experiment in Mexico because it is not now allowed in the United States. [emphasis mine]

…

When Science contacted Zhang, the physician initially said he barely knew He: [emphases mine] “I know him just like many people know him, in an academic meeting.”

…

After his talk [November 2018 at Hong Kong meeting], He immediately drove back to Shenzhen, and his circle of trust began to disintegrate. He has not spoken publicly since. “I don’t think he can recover himself through PR,” says Ferrell, who no longer works for He but recently started to do part-time work for He’s wife. “He has to do other service to the world.”

…

Calls for a moratorium on human germline editing have increased, although at the end of the Hong Kong summit, the organizing committee declined in its consensus to call for a ban. China has stiffened its regulations on work with human embryos, and Chinese bioethicists in a Nature editorial about the incident urged the country to confront “the eugenic thinking that has persisted among a small proportion of Chinese scholars.”

Church, who has many CRISPR collaborations in China, finds it inconceivable that He’s work surprised the Chinese government. China has “the best surveillance system in the world,” he says. “I conclude that they were totally aware of what he was doing at every step of the way, especially because he wasn’t particularly secretive about it.”

…

Benjamin Hurlbut, William’s son and a historian of biomedicine at Arizona State University in Tempe, says leaders in the scientific community should take a hard look at their actions, too. [emphases mine] He thinks the 2017 NASEM report helped give rise to He by following a well-established approach to guiding science: appointing an elite group to decide how scientists should be regulated. Benjamin Hurlbut, whose book Experiments in Democracy explores the governance of embryo research and bioethics, questions why small, scientist-led groups—à la the totemic Asilomar conference held in 1975 to discuss the future of recombinant DNA research—are seen as the best way to shape thinking about new technologies. Hurlbut has called for a “global observatory for gene editing” to convene meetings with diverse perspectives.

The prevailing notion that the scientific community simply “failed to see the rogue among the responsible,” Hurlbut says, is a convenient narrative for those scientific leaders and inhibits their ability to learn from such failures. [emphases mine] “It puts them on the right side of history,” he says. They failed to paint a bright enough red line, Hurlbut contends. “They are not on the right side of history because they contributed to this.”

…

If you have the time, I strongly recommend reading Cohen’s piece in its entirety. You’ll find links to the reports and more articles with in-depth reporting on this topic.

A little kindness and no regrets

William Hurlbut was interviewed in an As it happens (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’ CBC) radio programme segment on December 30, 2020. This is an excerpt from the story transcript written by Sheena Goodyear (Note: A link has been removed),

Dr. William Hurlbut, a physician and professor of neural-biology at Stanford University, says he tried to warn He to slow down before it was too late. Here is part of his conversation with As It Happens guest host Helen Mann.

What was your reaction to the news that Dr. He had been sentenced to three years in prison?

My first reaction was one of sadness because I know Dr. He — who we call J.K., that’s his nickname.

I spent quite a few hours talking with him, and I’m just sad that this worked out this way. It didn’t work out well for him or for his country or for the world, in some sense.

Except the one good thing is it’s alerted us, it’s awakened the world, to the seriousness of the issues that are coming down toward us with biotechnology, especially in genetics.

How does he feel about [how] not just the Chinese government, but the world generally, responded to his experiment?

He was surprised, personally. But I had actually warned him that he was proceeding too fast, and I didn’t know he had implanted embryos.

We had several conversations before this was disclosed, and I warned him to go more slowly and to keep in conversation with the rest of the international scientific community, and more broadly the international perspectives on social and ethical matters.

He was doing that to some extent, but not deeply enough and not transparently enough.

…

It sounds like you were very thoughtful in the conversations you had with him and the advice you gave him. And I guess you operated with what you had. But do you have any regrets yourself?

I don’t have any regrets about the way I conducted myself. I regret that this happened this way for J.K., who is a very bright person, and a very nice person, a humble person.

He grew up in a poor urban farming village. He told me that at one point he wanted to ask out a certain girl that he thought was really pretty … but he was embarrassed to do so because her family owned the restaurant. And so you see how humble his origins were.

By the way, he did end up asking her out and he ended up marrying her, which is a happy story, except now they’re separated for years of crucial time, and they have little children.

I know this is a bigger story than just J.K. and his family. But there’s a personal story to it too.

…

What happens He Jiankui? … Is his research career over?

It’s hard to imagine that a nation like China would not give him some some useful role in their society. A very intelligent and very well-educated young man.

But on the other hand, he will be forever a sign of a very crucial and difficult moment for the human species. He’s not going outlive that.

It’s going to be interesting. I hope I get a chance to have good conversations with him again and hear his internal ruminations and perspectives on it all.

This (“I don’t have any regrets about the way I conducted myself”) is where Hurlbut lost me. I think he could have suggested that he’d reviewed and rethought everything and feels that he and others could have done better and maybe they need to rethink how scientists are trained and how we talk about science, genetics, and emerging technology. Interestingly, it’s his son who comes up with something closer to what I’m suggesting (this excerpt was quoted earlier in this posting from a December 30, 2019 article, by Carolyn Y. Johnson for the Washington Post),

“The fact that the individual at the center of the story has been punished for his role in it should not distract us from examining what supporting roles were played by others, particularly in the international scientific community and also the environment that shaped and encouraged him to push the limits,” said Benjamin Hurlbut [emphasis mine], associate professor in the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University.

The man who CRISPRs himself approves

Josiah Zayner publicly injected himself with CRISPR in a demonstration (see my January 25, 2018 posting for details about Zayner, his demonstration, and his plans). As you might expect, his take on the He affair is quite individual. From a January 2, 2020 article for STAT, Zayner presents the case for Dr. He’s work (Note: Links have been removed),

When I saw the news that He Jiankui and colleagues had been sentenced to three years in prison for the first human embryo gene editing and implantation experiments, all I could think was, “How will we look back at what they had done in 100 years?”

When the scientist described his research and revealed the births of gene edited twin girls at the [Second] International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong in late November 2018, I stayed up into the early hours of the morning in Oakland, Calif., watching it. Afterward, I couldn’t sleep for a few days and couldn’t stop thinking about his achievement.

This was the first time a viable human embryo was edited and allowed to live past 14 days, much less the first time such an embryo was implanted and the baby brought to term.

The majority of scientists were outraged at the ethics of what had taken place, despite having very little information on what had actually occurred.

To me, no matter how abhorrent one views [sic] the research, it represents a substantial step forward in human embryo editing. Now there is a clear path forward that anyone can follow when before it had been only a dream.

…

As long as the children He Jiankui engineered haven’t been harmed by the experiment, he is just a scientist who forged some documents to convince medical doctors to implant gene-edited embryos. The 4-minute mile of human genetic engineering has been broken. It will happen again.

The academic establishment and federal funding regulations have made it easy to control the number of heretical scientists. We rarely if ever hear of individuals pushing the ethical and legal boundaries of science.

The rise of the biohacker is changing that.

A biohacker is a scientist who exists outside academia or an institution. By this definition, He Jiankui is a biohacker. I’m also part of this community, and helped build an organization to support it.

Such individuals have much more freedom than “traditional” scientists because scientific regulation in the U.S. is very much institutionally enforced by the universities, research organizations, or grant-giving agencies. But if you are your own institution and don’t require federal grants, who can police you? If you don’t tell anyone what you are doing, there is no way to stop you — especially since there is no government agency actively trying to stop people from editing embryos.

…

… When a human embryo being edited and implanted is no longer interesting enough for a news story, will we still view He Jiankui as a villain?

I don’t think we will. But even if we do, He Jiankui will be remembered and talked about more than any scientist of our day. Although that may seriously aggravate many scientists and bioethicists, I think he deserves that honor.

Josiah Zayner is CEO of The ODIN, a company that teaches people how to do genetic engineering in their homes.

You can find The ODIN here.

Final comments

There can’t be any question that this was inevitable. One needs only to take a brief stroll through the history of science to know that scientists are going to push boundaries or, as in this case, press past an ill-defined grey zone.

The only scientists who are being publicly punished for hubris are Dr. He Jiankui and his two colleagues in China. Dr. Michael Deem is still working for Rice University as far as I can determine. Here’s how the Wikipedia entry for the He Jiankui Affair describes the investigation (Note: Links have been removed),

Michael W. Deem, an American bioengineering professor at Rice University and He’s doctoral advisor, was involved in the research, and was present when people involved in He’s study gave consent.[24] He was the only non-Chinese out of 10 authors listed in the manuscript submitted to Nature.[30] Deem came under investigation by Rice University after news of the work was made public.[58] As of 31 December 2019, the university had not released a decision.[59] [emphasis mine]

Meanwhile the scientists at Stanford are cleared. While there are comments about the Chinese government not being transparent, it seems to me that US universities are just as opaque.

What seems missing from all this discussion and opprobrium is that the CRISPR technology itself is problematic. My September 20, 2019 post features research into off-target results from CRISPR gene-editing and, prior, there was this July 17, 2018 posting (The CRISPR [clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats]-CAS9 gene-editing technique may cause new genetic damage kerfuffle).

I’d like to see more discussion and, in line with Benjamin Hurlbut’s thinking, I’d like to see more than a small group of experts talking to each other as part of the process especially here in Canada and in light of efforts to remove our ban on germline-editing (see my April 26, 2019 posting for more about those efforts).