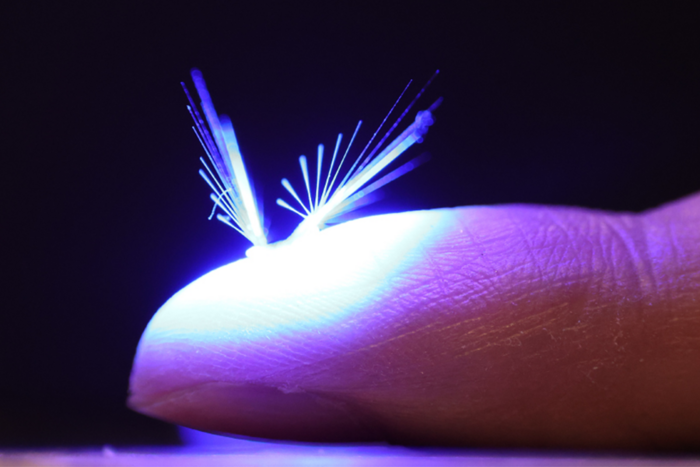

Giant clams in Palau (Cynthia Barnett)

These don’t look like any clams I’ve ever seen but that is the point of Cynthia Barnett’s absorbing Sept. 10, 2018 article for The Atlantic (Note: A link has been removed),

Snorkeling amid the tree-tangled rock islands of Ngermid Bay in the western Pacific nation of Palau, Alison Sweeney lingers at a plunging coral ledge, photographing every giant clam she sees along a 50-meter transect. In Palau, as in few other places in the world, this means she is going to be underwater for a skin-wrinkling long time.

At least the clams are making it easy for Sweeney, a biophysicist at the University of Pennsylvania. The animals plump from their shells like painted lips, shimmering in blues, purples, greens, golds, and even electric browns. The largest are a foot across and radiate from the sea floor, but most are the smallest of the giant clams, five-inch Tridacna crocea, living higher up on the reef. Their fleshy Technicolor smiles beam in all directions from the corals and rocks of Ngermid Bay.

…

… Some of the corals are bleached from the conditions in Ngermid Bay, where naturally high temperatures and acidity mirror the expected effects of climate change on the global oceans. (Ngermid Bay is more commonly known as “Nikko Bay,” but traditional leaders and government officials are working to revive the indigenous name of Ngermid.)

Even those clams living on bleached corals are pulsing color, like wildflowers in a white-hot desert. Sweeney’s ponytail flows out behind her as she nears them with her camera. They startle back into their fluted shells. Like bashful fairytale creatures cursed with irresistible beauty, they cannot help but draw attention with their sparkly glow.

Barnett makes them seem magical and perhaps they are (Note: A link has been removed),

It’s the glow that drew Sweeney’s attention to giant clams, and to Palau, a tiny republic of more than 300 islands between the Philippines and Guam. Its sun-laden waters are home to seven of the world’s dozen giant-clam species, from the storied Tridacna gigas—which can weigh an estimated 550 pounds and measure over four feet across—to the elegantly fluted Tridacna squamosa. Sweeney first came to the archipelago in 2009, while working on animal iridescence as a post-doctoral fellow at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Whether shimmering from a blue morpho butterfly’s wings or a squid’s skin, iridescence is almost always associated with a visual signal—one used to attract mates or confuse predators. Giant clams’ luminosity is not such a signal. So, what is it?

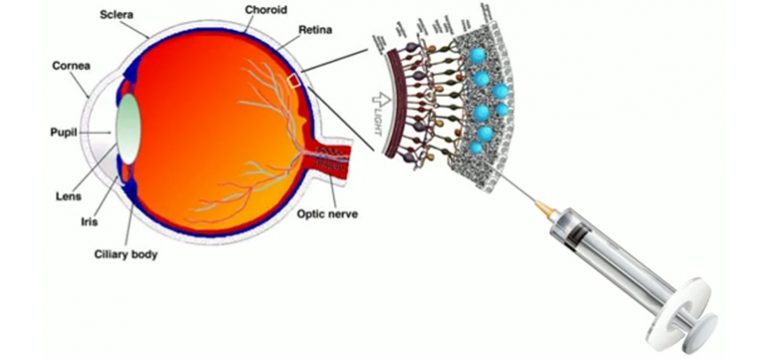

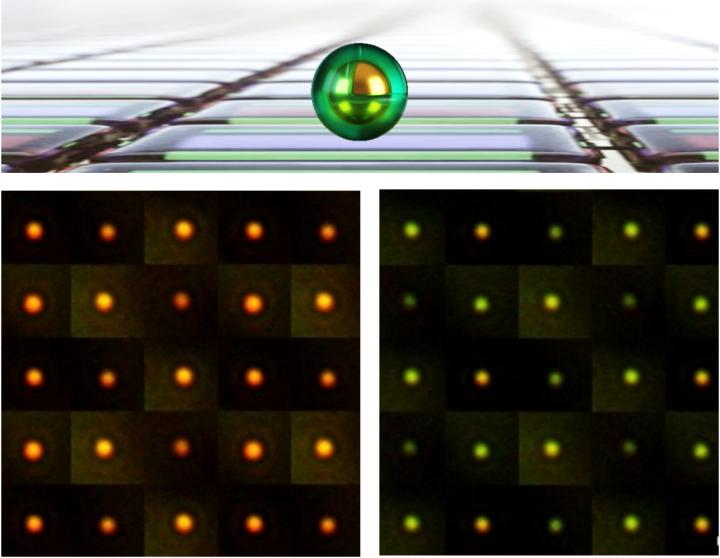

In the years since, Sweeney and her colleagues have discovered that the clams’ iridescence is essentially the outer glow of a solar transformer—optimized over millions of years to run on sunlight and algal biofuel. Giant clams reach their cartoonish proportions thanks to an exceptional ability to grow their own photosynthetic algae in vertical farms spread throughout their flesh. Sweeney and other scientists think this evolved expertise may shed light on alternative fuel technologies and other industrial solutions for a warming world.

Barnett goes on to describe Palau’s relationship to the clams and the clams’ environment,

Palau’s islands have been inhabited for at least 3,400 years, and from the start, giant clams were a staple of diet, daily life, and even deity. Many of the islands’ oldest-surviving tools are crafted of thick giant-clam shell: arched-blade adzes, fishhooks, gougers, heavy taro-root pounders. Giant-clam shell makes up more than three-fourths of some of the oldest shell middens in Palau, a percentage that decreases through the centuries. Archaeologists suggest that the earliest islanders depleted the giant clams that crowded the crystalline shallows, then may have self-corrected. Ancient Palauan conservation law, known as bul, prohibited fishing during critical spawning periods, or when a species showed signs of over-harvesting.

Before the Christianity that now dominates Palauan religion sailed in on eighteenth-century mission ships, the culture’s creation lore began with a giant clam called to life in an empty sea. The clam grew bigger and bigger until it sired Latmikaik, the mother of human children, who birthed them with the help of storms and ocean currents.

The legend evokes giant clams in their larval phase, moving with the currents for their first two weeks of life. Before they can settle, the swimming larvae must find and ingest one or two photosynthetic alga, which later multiply, becoming self-replicating fuel cells. After the larvae down the alga and develop a wee shell and a foot, they kick around like undersea farmers, looking for a sunny spot for their crop. When they’ve chosen a well-lit home in a shallow lagoon or reef, they affix to the rock, their shell gaping to the sky. After the sun hits and photosynthesis begins, the microalgae will multiply to millions, or in the case of T. gigas, billions, and clam and algae will live in symbiosis for life.

…

Giant clam is a beloved staple in Palau and many other Pacific islands, prepared raw with lemon, simmered into coconut soup, baked into a savory pancake, or sliced and sautéed in a dozen other ways. But luxury demand for their ivory-like shells and their adductor muscle, which is coveted as high-end sashimi and an alleged aphrodisiac, has driven T. gigas extinct in China, Taiwan, and other parts of their native habitat. Some of the toughest marine-protection laws in the world, along with giant-clam aquaculture pioneered here, have helped Palau’s wild clams survive. The Palau Mariculture Demonstration Center raises hundreds of thousands of giant clams a year, supplying local clam farmers who sell to restaurants and the aquarium trade and keeping pressure off the wild population. But as other nations have wiped out their clams, Palau’s 230,000-square-mile ocean territory is an increasing target of illegal foreign fishers.

Barnett delves into how the country of Palau is responding to the voracious appetite for the giant clams and other marine life,

Palau, drawing on its ancient conservation tradition of bul, is fighting back. In 2015, President Tommy Remengesau Jr. signed into law the Palau National Marine Sanctuary Act, which prohibits fishing in 80 percent of Palau’s Exclusive Economic Zone and creates a domestic fishing area in the remaining 20 percent, set aside for local fishers selling to local markets. In 2016, the nation received a $6.6 million grant from Japan to launch a major renovation of the Palau Mariculture Demonstration Center. Now under construction at the waterfront on the southern tip of Malakal Island, the new facility will amp up clam-aquaculture research and increase giant-clam production five-fold, to more than a million seedlings a year.

Last year, Palau amended its immigration policy to require that all visitors sign a pledge to behave in an ecologically responsible manner. The pledge, stamped into passports by an immigration officer who watches you sign, is written to the island’s children:

Children of Palau, I take this pledge, as your guest, to preserve and protect your beautiful and unique island home. I vow to tread lightly, act kindly and explore mindfully. I shall not take what is not given. I shall not harm what does not harm me. The only footprints I shall leave are those that will wash away.

The pledge is winning hearts and public-relations awards. But Palau’s existential challenge is still the collective “we,” the world’s rising carbon emissions and the resulting upturns in global temperatures, sea levels, and destructive storms.

F. Umiich Sengebau, Palau’s Minister for Natural Resources, Environment, and Tourism, grew up on Koror and is full of giant-clam proverbs, wisdom and legends from his youth. He tells me a story I also heard from an elder in the state of Airai: that in old times, giant clams were known as “stormy-weather food,” the fresh staple that was easy to collect and have on hand when it was too stormy to go out fishing.

As Palau faces the storms of climate change, Sengebau sees giant clams becoming another sort of stormy-weather food, serving as a secure source of protein; a fishing livelihood; a glowing icon for tourists; and now, an inspiration for alternative energy and other low-carbon technologies. “In the old days, clams saved us,” Sengebau tells me. “I think there’s a lot of power in that, a great power and meaning in the history of clams as food, and now clams as science.”

I highly recommend Barnett’s article, which is one article in a larger series, from a November 6, 2017 The Atlantic press release,

The Atlantic is expanding the global footprint of its science writing today with a multi-year series to investigate life in all of its multitudes. The series, “Life Up Close,” created with support from Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education (HHMI), begins today at TheAtlantic.com. In the first piece for the project, “The Zombie Diseases of Climate Change,” The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer travels to Greenland to report on the potentially dangerous microbes emerging from thawing Arctic permafrost.

The project is ambitious in both scope and geographic reach, and will explore how life is adapting to our changing planet. Journalists will travel the globe to examine these changes as they happen to microbes, plants, and animals in oceans, grasslands, forests, deserts, and the icy poles. The Atlantic will question where humans should look for life next: from the Martian subsurface, to Europa’s oceans, to the atmosphere of nearby stars and beyond. “Life Up Close” will feature at least twenty reported pieces continuing through 2018.

“The Atlantic has been around for 160 years, but that’s a mere pinpoint in history when it comes to questions of life and where it started, and where we’re going,” said Ross Andersen, The Atlantic’s senior editor who oversees science, tech, and health. “The questions that this project will set out to tackle are critical; and this support will allow us to cover new territory in new and more ambitious ways.”

…

About The Atlantic:

Founded in 1857 and today one of the fastest growing media platforms in the industry, The Atlantic has throughout its history championed the power of big ideas and continues to shape global debate across print, digital, events, and video platforms. With its award-winning digital presence TheAtlantic.com and CityLab.com on cities around the world, The Atlantic is a multimedia forum on the most critical issues of our times—from politics, business, urban affairs, and the economy, to technology, arts, and culture. The Atlantic is celebrating its 160th anniversary this year. Bob Cohn is president of The Atlantic and Jeffrey Goldberg is editor in chief.

About the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Department of Science Education:

HHMI is the leading private nonprofit supporter of scientific research and science education in the United States. The Department of Science Education’s BioInteractive division produces free, high quality educational media for science educators and millions of students around the globe, its HHMI Tangled Bank Studios unit crafts powerful stories of scientific discovery for television and big screens, and its grants program aims to transform science education in universities and colleges. For more information, visit www.hhmi.org.

Getting back to the giant clams, sometimes all you can do is marvel, eh?