This started out as an update and now it’s something else. What follows is a brief introduction to the Chinese CRISPR twins; a brief examination of parents, children, and competitiveness; and, finally, a suggestion that genes may not be what we thought. I also include a discussion about how some think scientists should respond when they know beforehand that one of their kin is crossing an ethical line. Basically, this is a complex topic and I am attempting to interweave a number of competing lines of query into one narrative about human nature and the latest genetics obsession.

Introduction to the Chinese CRISPR twins

Back in November 2018 I covered the story about the Chinese scientist, He Jiankui , who had used CRISPR technology to edit genes in embryos that were subsequently implanted in a waiting mother (apparently there could be as many as eight mothers) with the babies being brought to term despite an international agreement (of sorts) not to do that kind of work. At this time, we know of the twins, Lulu and Nana but, by now, there may be more babies. (I have much more detail about the initial controversies in my November 28, 2018 posting.)

It seems the drama has yet to finish unfolding. There may be another consequence of He’s genetic tinkering.

Could the CRISPR babies, Lulu and Nana, have enhanced cognitive abilities?

Yes, according to Antonio Regalado’s February 21, 2019 article (behind a paywall) for MIT’s (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Technology Review, those engineered babies may have enhanced abilities for learning and remembering.

For those of us who can’t get beyond the paywall, others have been successful. Josh Gabbatiss in his February 22, 2019 article for independent.co.uk provides some detail,

The world’s first gene edited babies may have had their brains unintentionally altered – and perhaps cognitively enhanced – as a result of the controversial treatment undertaken by a team of Chinese scientists.

Dr He Jiankui and his team allegedly deleted a gene from a number of human embryos before implanting them in their mothers, a move greeted with horror by the global scientific community. The only known successful birth so far is the case of twin girls Nana and Lulu.

The now disgraced scientist claimed that he removed a gene called CCR5 [emphasis mine] from their embroyos in an effort to make the twins resistant to infection by HIV.

But another twist in the saga has now emerged after a new paper provided more evidence that the impact of CCR5 deletion reaches far beyond protection against dangerous viruses – people who naturally lack this gene appear to recover more quickly from strokes, and even go further in school. [emphasis mine]

Dr Alcino Silva, a neurobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who helped identify this role for CCR5 said the work undertaken by Dr Jiankui likely did change the girls’ brains.

“The simplest interpretation is that those mutations will probably have an impact on cognitive function in the twins,” he told the MIT Technology Review.

The connection immediately raised concerns that the gene was targeted due to its known links with intelligence, which Dr Silva said was his immediate response when he heard the news.

…

… there is no evidence that this was Dr Jiankui’s goal and at a press conference organised after the initial news broke, he said he was aware of the work but was “against using genome editing for enhancement”.

..

Claire Maldarelli’s February 22, 2019 article for Popular Science provides more information about the CCR5 gene/protein (Note: Links have been removed),

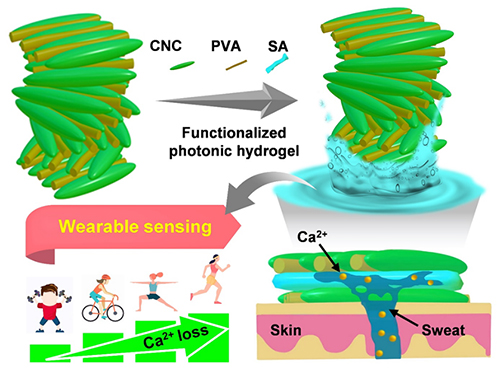

CCR5 is a protein that sits on the surface of white blood cells, a major component of the human immune system. There, it allows HIV to enter and infect a cell. A chunk of the human population naturally carries a mutation that makes CCR5 nonfunctional (one study found that 10 percent of Europeans have this mutation), which often results in a smaller protein size and one that isn’t located on the outside of the cell, preventing HIV from ever entering and infecting the human immune system.

The goal of the Chinese researchers’ work, led by He Jiankui of the Southern University of Science and Technology located in Shenzhen, was to tweak the embryos’ genome to lack CCR5, ensuring the babies would be immune to HIV.

But genetics is rarely that simple.

In recent years, the CCR5 gene has been a target of ongoing research, and not just for its relationship to HIV. In an attempt to understand what influences memory formation and learning in the brain, a group of researchers at UCLA found that lowering the levels of CCR5 production enhanced both learning and memory formation. This connection led those researchers to think that CCR5 could be a good drug target for helping stroke victims recover: Relearning how to move, walk, and talk is a key component to stroke rehabilitation.

…

… promising research, but it begs the question: What does that mean for the babies who had their CCR5 genes edited via CRISPR prior to their birth? Researchers speculate that the alternation will have effects on the children’s cognitive functioning. …

John Loeffler’s February 22, 2019 article for interestingengineering.com notes that there are still many questions about He’s (scientist’s name) research including, did he (pronoun) do what he claimed? (Note: Links have been removed),

Considering that no one knows for sure whether He has actually done as he and his team claim, the swiftness of the condemnation of his work—unproven as it is—shows the sensitivity around this issue.

Whether He did in fact edit Lulu and Nana’s genes, it appears he didn’t intend to impact their cognitive capacities. According to MIT Technology Review, not a single researcher studying CCR5’s role in intelligence was contacted by He, even as other doctors and scientists were sought out for advice about his project.

This further adds to the alarm as there is every expectation that He should have known about the connection between CCR5 and cognition.

At a gathering of gene-editing researchers in Hong Kong two days after the birth of the potentially genetically-altered twins was announced, He was asked about the potential impact of erasing CCR5 from the twins DNA on their mental capacity.

…

He responded that he knew about the potential cognitive link shown in Silva’s 2016 research. “I saw that paper, it needs more independent verification,” He said, before adding that “I am against using genome editing for enhancement.”

The problem, as Silva sees it, is that He may be blazing the trail for exactly that outcome, whether He intends to or not. Silva says that after his 2016 research was published, he received an uncomfortable amount of attention from some unnamed, elite Silicon Valley leaders who seem to be expressing serious interest in using CRISPR to give their children’s brains a boost through gene editing. [emphasis mine]

As such, Silva can be forgiven for not quite believing He’s claims that he wasn’t intending to alter the human genome for enhancement. …

…

The idea of designer babies isn’t new. As far back as Plato, the thought of using science to “engineer” a better human has been tossed about, but other than selective breeding, there really hasn’t been a path forward.

In the late 1800s, early 1900s, Eugenics made a real push to accomplish something along these lines, and the results were horrifying, even before Nazism. After eugenics mid-wifed the Holocaust in World War II, the concept of designer children has largely been left as fodder for science fiction since few reputable scientists would openly declare their intention to dabble in something once championed and pioneered by the greatest monsters of the 20th century.

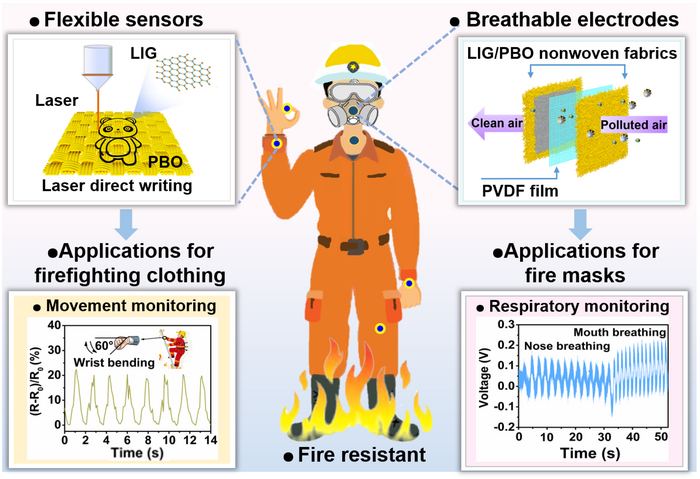

Memories have faded though, and CRISPR significantly changes this decades-old calculus. CRISPR makes it easier than ever to target specific traits in order to add or subtract them from an embryos genetic code. Embryonic research is also a diverse enough field that some scientist could see pioneering designer babies as a way to establish their star power in academia while getting their names in the history books, [emphasis mine] all while working in relative isolation. They only need to reveal their results after the fact and there is little the scientific community can do to stop them, unfortunately.

…

When He revealed his research and data two days after announcing the births of Lulu and Nana, the gene-scientists at the Hong Kong conference were not all that impressed with the quality of He’s work. He has not provided access for fellow researchers to either his data on Lulu, Nana, and their family’s genetic data so that others can verify that Lulu and Nana’s CCR5 genes were in fact eliminated.

This almost rudimentary verification and validation would normally accompany a major announcement such as this. Neither has He’s work undergone a peer-review process and it hasn’t been formally published in any scientific journal—possibly for good reason.

Researchers such as Eric Topol, a geneticist at the Scripps Research Institute, have been finding several troubling signs in what little data He has released. Topol says that the editing itself was not precise and show “all kinds of glitches.”

Gaetan Burgio, a geneticist at the Australian National University, is likewise unimpressed with the quality of He’s work. Speaking of the slides He showed at the conference to support his claim, Burgio calls it amateurish, “I can believe that he did it because it’s so bad.”

Worse of all, its entirely possible that He actually succeeded in editing Lulu and Nana’s genetic code in an ad hoc, unethical, and medically substandard way. Sadly, there is no shortage of families with means who would be willing to spend a lot of money to design their idea of a perfect child, so there is certainly demand for such a “service.”

…

It’s nice to know (sarcasm icon) that the ‘Silicon Valley elite’ are willing to volunteer their babies for scientific experimentation in a bid to enhance intelligence.

The ethics of not saying anything

Natalie Kofler, a molecular biologist, wrote a February 26, 2019 Nature opinion piece and call to action on the subject of why scientists who were ‘in the know’ remained silent about He’s work prior to his announcements,

Millions [?] were shocked to learn of the birth of gene-edited babies last year, but apparently several scientists were already in the know. Chinese researcher He Jiankui had spoken with them about his plans to genetically modify human embryos intended for pregnancy. His work was done before adequate animal studies and in direct violation of the international scientific consensus that CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing technology is not ready or appropriate for making changes to humans that could be passed on through generations.

Scholars who have spoken publicly about their discussions with He described feeling unease. They have defended their silence by pointing to uncertainty over He’s intentions (or reassurance that he had been dissuaded), a sense of obligation to preserve confidentiality and, perhaps most consistently, the absence of a global oversight body. Others who have not come forward probably had similar rationales. But He’s experiments put human health at risk; anyone with enough knowledge and concern could have posted to blogs or reached out to their deans, the US National Institutes of Health or relevant scientific societies, such as the Association for Responsible Research and Innovation in Genome Editing (see page 440). Unfortunately, I think that few highly established scientists would have recognized an obligation to speak up.

I am convinced that this silence is a symptom of a broader scientific cultural crisis: a growing divide between the values upheld by the scientific community and the mission of science itself.

A fundamental goal of the scientific endeavour is to advance society through knowledge and innovation. As scientists, we strive to cure disease, improve environmental health and understand our place in the Universe. And yet the dominant values ingrained in scientists centre on the virtues of independence, ambition and objectivity. That is a grossly inadequate set of skills with which to support a mission of advancing society.

…

Editing the genes of embryos could change our species’ evolutionary trajectory. Perhaps one day, the technology will eliminate heritable diseases such as sickle-cell anaemia and cystic fibrosis. But it might also eliminate deafness or even brown eyes. In this quest to improve the human race, the strengths of our diversity could be lost, and the rights of already vulnerable populations could be jeopardized.

Decisions about how and whether this technology should be used will require an expanded set of scientific virtues: compassion to ensure its applications are designed to be just, humility to ensure its risks are heeded and altruism to ensure its benefits are equitably distributed.

…

Calls for improved global oversight and robust ethical frameworks are being heeded. Some researchers who apparently knew of He’s experiments are under review by their universities. Chinese investigators have said He skirted regulations and will be punished. But punishment is an imperfect motivator. We must foster researchers’ sense of societal values.

Fortunately, initiatives popping up throughout the scientific community are cultivating a scientific culture informed by a broader set of values and considerations. The Scientific Citizenship Initiative at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, trains scientists to align their research with societal needs. The Summer Internship for Indigenous Peoples in Genomics offers genomics training that also focuses on integrating indigenous cultural perspectives into gene studies. The AI Now Institute at New York University has initiated a holistic approach to artificial-intelligence research that incorporates inclusion, bias and justice. And Editing Nature, a programme that I founded, provides platforms that integrate scientific knowledge with diverse cultural world views to foster the responsible development of environmental genetic technologies.

Initiatives such as these are proof [emphasis mine] that science is becoming more socially aware, equitable and just. …

I’m glad to see there’s work being done on introducing a broader set of values into the scientific endeavour. That said, these programmes seem to be voluntary, i.e., people self-select, and those most likely to participate in these programmes are the ones who might be inclined to integrate social values into their work in the first place.

This doesn’t address the issue of how to deal with unscrupulous governments pressuring scientists to create designer babies along with hypercompetitive and possibly unscrupulous individuals such as the members of the ‘Silicon Valley insiders mentioned in Loeffler’s article, teaming up with scientists who will stop at nothing to get their place in the history books.

Like Kofler, I’m encouraged to see these programmes but I’m a little less convinced that they will be enough. What form it might take I don’t know but I think something a little more punitive is also called for.

CCR5 and freedom from HIV

I’ve added this piece about the Berlin and London patients because, back in November 2018, I failed to realize how compelling the idea of eradicating susceptibility to AIDS/HIV might be. Reading about some real life remissions helped me to understand some of He’s stated motivations a bit better. Unfortunately, there’s a major drawback described here in a March 5, 2019 news item on CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) online news attributed to Reuters,

An HIV-positive man in Britain has become the second known adult worldwide to be cleared of the virus that causes AIDS after he received a bone marrow transplant from an HIV-resistant donor, his doctors said.

The therapy had an early success with a man known as “the Berlin patient,” Timothy Ray Brown, a U.S. man treated in Germany who is 12 years post-transplant and still free of HIV. Until now, Brown was the only person thought to have been cured of infection with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

Such transplants are dangerous and have failed in other patients. They’re also impractical to try to cure the millions already infected.

In the latest case, the man known as “the London patient” has no trace of HIV infection, almost three years after he received bone marrow stem cells from a donor with a rare genetic mutation that resists HIV infection — and more than 18 months after he came off antiretroviral drugs.

“There is no virus there that we can measure. We can’t detect anything,” said Ravindra Gupta, a professor and HIV biologist who co-led a team of doctors treating the man.

Gupta described his patient as “functionally cured” and “in remission,” but cautioned: “It’s too early to say he’s cured.”

…

Gupta, now at Cambridge University, treated the London patient when he was working at University College London. The man, who has asked to remain anonymous, had contracted HIV in 2003, Gupta said, and in 2012 was also diagnosed with a type of blood cancer called Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

…

In 2016, when he was very sick with cancer, doctors decided to seek a transplant match for him.

“This was really his last chance of survival,” Gupta told Reuters.

Doctors found a donor with a gene mutation known as CCR5 delta 32, which confers resistance to HIV. About one per cent of people descended from northern Europeans have inherited the mutation from both parents and are immune to most HIV. The donor had this double copy of the mutation.

That was “an improbable event,” Gupta said. “That’s why this has not been observed more frequently.”

…

Most experts say it is inconceivable such treatments could be a way of curing all patients. The procedure is expensive, complex and risky. To do this in others, exact match donors would have to be found in the tiny proportion of people who have the CCR5 mutation.

Specialists said it is also not yet clear whether the CCR5 resistance is the only key [emphasis mine] — or whether the graft-versus-host disease may have been just as important. Both the Berlin and London patients had this complication, which may have played a role in the loss of HIV-infected cells, Gupta said.

…

Not only is there some question as to what role the CCR5 gene plays, there’s also a question as to whether or not we know what role genes play.

A big question: are genes what we thought?

Ken Richardson’s January 3, 2019 article for Nautilus (I stumbled across it on May 14, 2019 so I’m late to the party) makes and supports a startling statement, It’s the End of the Gene As We Know It We are not nearly as determined by our genes as once thought (Note: A link has been removed),

We’ve all seen the stark headlines: “Being Rich and Successful Is in Your DNA” (Guardian, July 12); “A New Genetic Test Could Help Determine Children’s Success” (Newsweek, July 10); “Our Fortunetelling Genes” make us (Wall Street Journal, Nov. 16); and so on.

The problem is, many of these headlines are not discussing real genes at all, but a crude statistical model of them, involving dozens of unlikely assumptions. Now, slowly but surely, that whole conceptual model of the gene is being challenged.

We have reached peak gene, and passed it.

…

The preferred dogma started to appear in different versions in the 1920s. It was aptly summarized by renowned physicist Erwin Schrödinger in a famous lecture in Dublin in 1943. He told his audience that chromosomes “contain, in some kind of code-script, the entire pattern of the individual’s future development and of its functioning in the mature state.”

Around that image of the code a whole world order of rank and privilege soon became reinforced. These genes, we were told, come in different “strengths,” different permutations forming ranks that determine the worth of different “races” and of different classes in a class-structured society. A whole intelligence testing movement was built around that preconception, with the tests constructed accordingly.

The image fostered the eugenics and Nazi movements of the 1930s, with tragic consequences. Governments followed a famous 1938 United Kingdom education commission in decreeing that, “The facts of genetic inequality are something that we cannot escape,” and that, “different children … require types of education varying in certain important respects.”

…

Today, 1930s-style policy implications are being drawn once again. Proposals include gene-testing at birth for educational intervention, embryo selection for desired traits, identifying which classes or “races” are fitter than others, and so on. And clever marketizing now sees millions of people scampering to learn their genetic horoscopes in DNA self-testing kits.[emphasis mine]

So the hype now pouring out of the mass media is popularizing what has been lurking in the science all along: a gene-god as an entity with almost supernatural powers. Today it’s the gene that, in the words of the Anglican hymn, “makes us high and lowly and orders our estate.”

…

… at the same time, a counter-narrative is building, not from the media but from inside science itself.

…

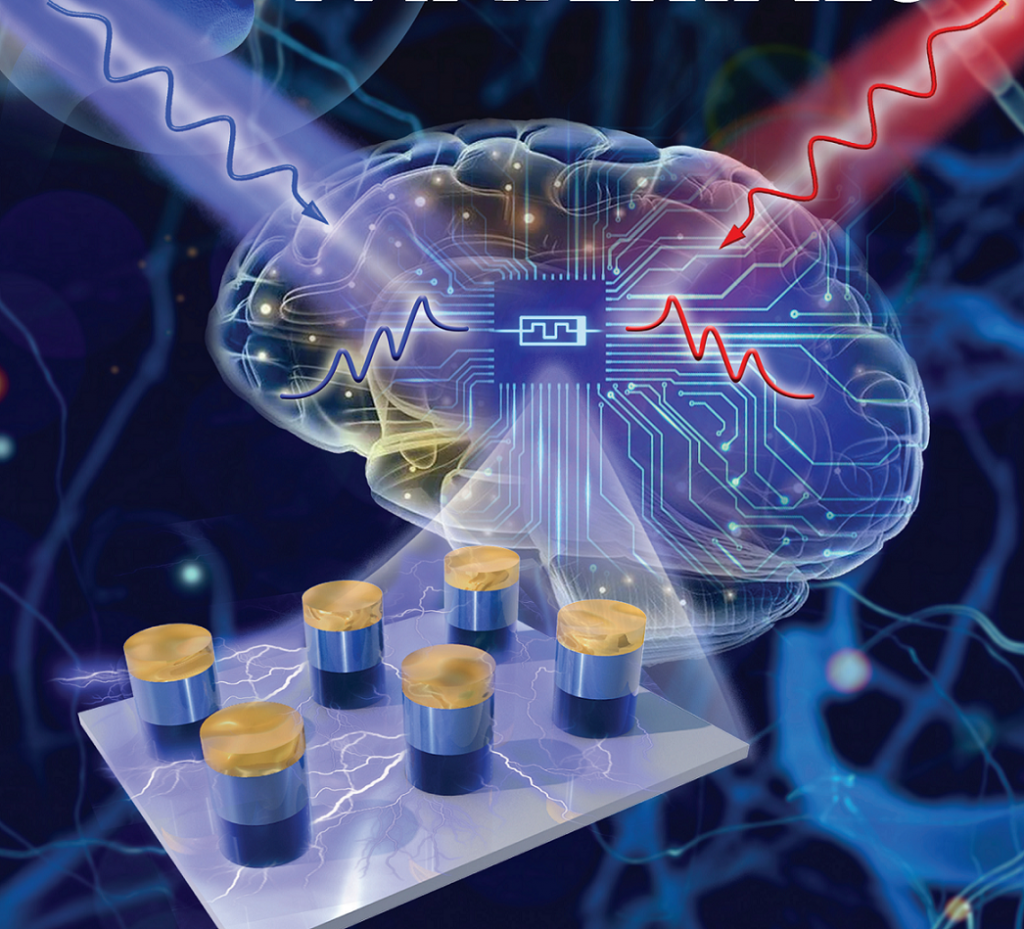

So it has been dawning on us is that there is no prior plan or blueprint for development: Instructions are created on the hoof, far more intelligently than is possible from dumb DNA. That is why today’s molecular biologists are reporting “cognitive resources” in cells; “bio-information intelligence”; “cell intelligence”; “metabolic memory”; and “cell knowledge”—all terms appearing in recent literature.1,2 “Do cells think?” is the title of a 2007 paper in the journal Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences.3 On the other hand the assumed developmental “program” coded in a genotype has never been described.

…

It is such discoveries that are turning our ideas of genetic causation inside out. We have traditionally thought of cell contents as servants to the DNA instructions. But, as the British biologist Denis Noble insists in an interview with the writer Suzan Mazur,1 “The modern synthesis has got causality in biology wrong … DNA on its own does absolutely nothing [ emphasis mine] until activated by the rest of the system … DNA is not a cause in an active sense. I think it is better described as a passive data base which is used by the organism to enable it to make the proteins that it requires.”

…

I highly recommend reading Richardson’s article in its entirety. As well, you may want to read his book, ” Genes, Brains and Human Potential: The Science and Ideology of Intelligence .”

As for “DNA on its own doing absolutely nothing,” that might be a bit of a eye-opener for the Silicon Valley elite types investigating cognitive advantages attributed to the lack of a CCR5 gene. Meanwhile, there are scientists inserting a human gene associated with brain development into monkeys,

Transgenic monkeys and human intelligence

An April 2, 2019 news item on chinadaily.com describes research into transgenic monkeys,

Researchers from China and the United States have created transgenic monkeys carrying a human gene that is important for brain development, and the monkeys showed human-like brain development.

Scientists have identified several genes that are linked to primate brain size. MCPH1 is a gene that is expressed during fetal brain development. Mutations in MCPH1 can lead to microcephaly, a developmental disorder characterized by a small brain.

In the study published in the Beijing-based National Science Review, researchers from the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the University of North Carolina in the United States and other research institutions reported that they successfully created 11 transgenic rhesus monkeys (eight first-generation and three second-generation) carrying human copies of MCPH1.

According to the research article, brain imaging and tissue section analysis showed an altered pattern of neuron differentiation and a delayed maturation of the neural system, which is similar to the developmental delay (neoteny) in humans.

Neoteny in humans is the retention of juvenile features into adulthood. One key difference between humans and nonhuman primates is that humans require a much longer time to shape their neuro-networks during development, greatly elongating childhood, which is the so-called “neoteny.”

…

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Transgenic rhesus monkeys carrying the human MCPH1 gene copies show human-like neoteny of brain development by Lei Shi, Xin Luo, Jin Jiang, Yongchang Chen, Cirong Liu, Ting Hu, Min Li, Qiang Lin, Yanjiao Li, Jun Huang Hong Wang, Yuyu Niu, Yundi Shi, Martin Styner, Jianhong Wang, Yi Lu, Xuejin Sun, Hualin Yu, Weizhi Ji, Bing Su. National Science Review, nwz043, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwz043 Published: 27 March 2019

This appears to be an open access paper,

Transgenic monkeys and an ethical uproar

Predictably, this research set off alarms as Sharon Kirkey’s April 12, 2019 article for the National Post describes in detail (Note: A link has been removed)l,

Their brains may not be bigger than normal, but monkeys created with human brain genes are exhibiting cognitive changes that suggest they might be smarter — and the experiments have ethicists shuddering.

In the wake of the genetically modified human babies scandal, Chinese scientists [as a scientist from the US] are drawing fresh condemnation from philosophers and ethicists, this time over the announcement they’ve created transgenic monkeys with elements of a human brain.

…

Six of the monkeys died, however the five survivors “exhibited better short-term memory and shorter reaction time” compared to their wild-type controls, the researchers report in the journa.

According to the researchers, the experiments represent the first attempt to study the genetic basis of human brain origin using transgenic monkeys. The findings, they insist, “have the potential to provide important — and potentially unique — insights into basic questions of what actually makes humans unique.”

For others, the work provokes a profoundly moral and visceral uneasiness. Even one of the collaborators — University of North Carolina computer scientist Martin Styner — told MIT Technology Review he considered removing his name from the paper, which he said was unable to find a publisher in the West.

“Now we have created this animal which is different than it is supposed to be,” Styner said. “When we do experiments, we have to have a good understanding of what we are trying to learn, to help society, and that is not the case here.” l

In an email to the National Post, Styner said he has an expertise in medical image analysis and was approached by the researchers back in 2011. He said he had no input on the science in the project, beyond how to best do the analysis of their MRI data. “At the time, I did not think deeply enough about the ethical consideration.”

….

When it comes to the scientific use of nonhuman primates, ethicists say the moral compass is skewed in cases like this.

Given the kind of beings monkeys are, “I certainly would have thought you would have had to have a reasonable expectation of high benefit to human beings to justify the harms that you are going to have for intensely social, cognitively complex, emotional animals like monkeys,” said Letitia Meynell, an associate professor in the department of philosophy at Dalhousie University in Halifax.

“It’s not clear that this kind of research has any reasonable expectation of having any useful application for human beings,” she said.

The science itself is also highly dubious and fundamentally flawed in its logic, she said.

“If you took Einstein as a baby and you raised him in the lab he wouldn’t turn out to be Einstein,” Meynell said. “If you’re actually interested in studying the cognitive complexity of these animals, you’re not going to get a good representation of that by raising them in labs, because they can’t develop the kind of cognitive and social skills they would in their normal environment.”

The Chinese said the MCPH1 gene is one of the strongest candidates for human brain evolution. But looking at a single gene is just bad genetics, Meynell said. Multiple genes and their interactions affect the vast majority of traits.

…

My point is that there’s a lot of research focused on intelligence and genes when we don’t really know what role genes actually play and when there doesn’t seem to be any serious oversight.

Global plea for moratorium on heritable genome editing

A March 13, 2019 University of Otago (New Zealand) press release (also on EurekAlert) describes a global plea for a moratorium,

A University of Otago bioethicist has added his voice to a global plea for a moratorium on heritable genome editing from a group of international scientists and ethicists in the wake of the recent Chinese experiment aiming to produce HIV immune children.

In an article in the latest issue of international scientific journal Nature, Professor Jing-Bao Nie together with another 16 [17] academics from seven countries, call for a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing to make genetically modified children.

They would like an international governance framework – in which nations voluntarily commit to not approve any use of clinical germline editing unless certain conditions are met – to be created potentially for a five-year period.

Professor Nie says the scientific scandal of the experiment that led to the world’s first genetically modified babies raises many intriguing ethical, social and transcultural/transglobal issues. His main personal concerns include what he describes as the “inadequacy” of the Chinese and international responses to the experiment.

“The Chinese authorities have conducted a preliminary investigation into the scientist’s genetic misadventure and issued a draft new regulation on the related biotechnologies. These are welcome moves. Yet, by putting blame completely on the rogue scientist individually, the institutional failings are overlooked,” Professor Nie explains.

“In the international discourse, partly due to the mentality of dichotomising China and the West, a tendency exists to characterise the scandal as just a Chinese problem. As a result, the global context of the experiment and Chinese science schemes have been far from sufficiently examined.”

The group of 17 [18] scientists and bioethicists say it is imperative that extensive public discussions about the technical, scientific, medical, societal, ethical and moral issues must be considered before germline editing is permitted. A moratorium would provide time to establish broad societal consensus and an international framework.

“For germline editing to even be considered for a clinical application, its safety and efficacy must be sufficient – taking into account the unmet medical need, the risks and potential benefits and the existence of alternative approaches,” the opinion article states.

Although techniques have improved in recent years, germline editing is not yet safe or effective enough to justify any use in the clinic with the risk of failing to make the desired change or of introducing unintended mutations still unacceptably high, the scientists and ethicists say.

“No clinical application of germline editing should be considered unless its long-term biological consequences are sufficiently understood – both for individuals and for the human species.”

The proposed moratorium does not however, apply to germline editing for research uses or in human somatic (non-reproductive) cells to treat diseases.

Professor Nie considers it significant that current presidents of the UK Royal Society, the US National Academy of Medicine and the Director and Associate Director of the US National Institute of Health have expressed their strong support for such a proposed global moratorium in two correspondences published in the same issue of Nature. The editorial in the issue also argues that the right decision can be reached “only through engaging more communities in the debate”.

“The most challenging questions are whether international organisations and different countries will adopt a moratorium and if yes, whether it will be effective at all,” Professor Nie says.

A March 14, 2019 news item on phys.org provides a précis of the Comment in Nature. Or, you ,can access the Comment with this link

Adopt a moratorium on heritable genome editing; Eric Lander, Françoise Baylis, Feng Zhang, Emmanuelle Charpentier, Paul Berg and specialists from seven countries call for an international governance framework.signed by: Eric S. Lander, Françoise Baylis, Feng Zhang, Emmanuelle Charpentier, Paul Berg, Catherine Bourgain, Bärbel Friedrich, J. Keith Joung, Jinsong Li, David Liu, Luigi Naldini, Jing-Bao Nie, Renzong Qiu, Bettina Schoene-Seifert, Feng Shao, Sharon Terry, Wensheng Wei, & Ernst-Ludwig Winnacker. Nature 567, 165-168 (2019) doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00726-5

This Comment in Nature is open access.

World Health Organization (WHO) chimes in

Better late than never, eh? The World Health Organization has called heritable gene editing of humans ‘irresponsible’ and made recommendations. From a March 19, 2019 news item on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Online news webpage,

A panel convened by the World Health Organization said it would be “irresponsible” for scientists to use gene editing for reproductive purposes, but stopped short of calling for a ban.

The experts also called for the U.N. health agency to create a database of scientists working on gene editing. The recommendation was announced Tuesday after a two-day meeting in Geneva to examine the scientific, ethical, social and legal challenges of such research.

“At this time, it is irresponsible for anyone to proceed” with making gene-edited babies since DNA changes could be passed down to future generations, the experts said in a statement.

Germline editing has been on my radar since 2015 (see my May 14, 2015 posting) and the probability that someone would experiment with viable embryos and bring them to term shouldn’t be that much of a surprise.

Slow science from Canada

Canada has banned germline editing but there is pressure to lift that ban. (I touched on the specifics of the campaign in an April 26, 2019 posting.) This March 17, 2019 essay on The Conversation by Landon J Getz and Graham Dellaire, both of Dalhousie University (Nova Scotia, Canada) elucidates some of the discussion about whether research into germline editing should be slowed down.

Naughty (or Haughty, if you prefer) scientists

There was scoffing from some, if not all, members of the scientific community about the potential for ‘designer babies’ that can be seen in an excerpt from an article by Ed Yong for The Atlantic (originally published in my ,August 15, 2017 posting titled: CRISPR and editing the germline in the US (part 2 of 3): ‘designer babies’?),

Ed Yong in an Aug. 2, 2017 article for The Atlantic offered a comprehensive overview of the research and its implications (unusually for Yong, there seems to be mildly condescending note but it’s worth ignoring for the wealth of information in the article; Note: Links have been removed),

” … the full details of the experiment, which are released today, show that the study is scientifically important but much less of a social inflection point than has been suggested. “This has been widely reported as the dawn of the era of the designer baby, making it probably the fifth or sixth time people have reported that dawn,” says Alta Charo, an expert on law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “And it’s not.”

…

Then about 15 months later, the possibility seemed to be realized.

Interesting that scientists scoffed at the public’s concerns (you can find similar arguments about robots and artificial intelligence not being a potentially catastrophic problem), yes? Often, nonscientists’ concerns are dismissed as being founded in science fiction.

To be fair, there are times when concerns are overblown, the difficulty is that it seems the scientific community’s default position is to uniformly dismiss concerns rather than approaching them in a nuanced fashion. If the scoffers had taken the time to think about it, germline editing on viable embryos seems like an obvious and inevitable next step (as I’ve noted previously).

At this point, no one seems to know if He actually succeeded at removing CCR5 from Lulu’s and Nana’s genomes. In November 2018, scientists were guessing that at least one of the twins was a ‘mosaic’. In other words, some of her cells did not include CCR5 while others did.

Parents, children, competition

A recent college admissions scandal in the US has highlighted the intense competition to get into high profile educational institutions. (This scandal brought to mind the Silicon Valey elite who wanted to know more about gene editing that might result in improved cognitive skills.)

Since it can be easy to point the finger at people in other countries, I’d like to note that there was a Canadian parent among these wealthy US parents attempting to give their children advantages by any means, legal or not. (Note: These are alleged illegalities.) From a March 12, 2019 news article by Scott Brown, Kevin Griffin, and Keith Fraser for the Vancouver Sun,

Vancouver businessman and former CFL [Canadian Football League] player David Sidoo has been charged with conspiracy to commit mail and wire fraud in connection with a far-reaching FBI investigation into a criminal conspiracy that sought to help privileged kids with middling grades gain admission to elite U.S. universities.

In a 12-page indictment filed March 5 [2019] in the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts, Sidoo is accused of making two separate US$100,000 payments to have others take college entrance exams in place of his two sons.

Sidoo is also accused of providing documents for the purpose of creating falsified identification cards for the people taking the tests.

In what is being called the biggest college-admissions scam ever prosecuted by the U.S. Justice Department, Sidoo has been charged with nearly 50 other people. Nine athletic coaches and 33 parents including Hollywood actresses Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin. are among those charged in the investigation, dubbed Operation Varsity Blues.

…

According to the indictment, an unidentified person flew from Tampa, Fla., to Vancouver in 2011 to take the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) in place of Sidoo’s older son and was directed not to obtain too high a score since the older son had previously taken the exam, obtaining a score of 1460 out of a possible 2400.

A copy of the resulting SAT score — 1670 out of 2400 — was mailed to Chapman University, a private university in Orange, Calif., on behalf of the older son, who was admitted to and ultimately enrolled in the university in January 2012, according to the indictment.

It’s also alleged that Sidoo arranged to have someone secretly take the older boy’s Canadian high school graduation exam, with the person posing as the boy taking the exam in June 2012.

The Vancouver businessman is also alleged to have paid another $100,000 to have someone take the SAT in place of his younger son.

…

Sidoo, an investment banker currently serving as CEO of Advantage Lithium, was awarded the Order of B.C. in 2016 for his philanthropic efforts.

He is a former star with the UBC [University of British Columbia] Thunderbirds football team and helped the school win its first Vanier Cup in 1982. He went on to play five seasons in the CFL with the Saskatchewan Roughriders and B.C. Lions.

Sidoo is a prominent donor to UBC and is credited with spearheading an alumni fundraising campaign, 13th Man Foundation, that resuscitated the school’s once struggling football team. He reportedly donated $2 million of his own money to support the program.

Sidoo Field at UBC’s Thunderbird Stadium is named in his honour.

In 2016, he received the B.C. [British Columbia] Sports Hall of Fame’s W.A.C. Bennett Award for his contributions to the sporting life of the province.

…

The question of whether or not these people like the ‘Silicon Valley elite’ (mentioned in John Loeffler’s February 22, 2019 article) would choose to tinker with their children’s genome if it gave them an advantage, is still hypothetical but it’s easy to believe that at least some might seriously consider the possibility especially if the researcher or doctor didn’t fully explain just how little is known about the impact of tinkering with the genome. For example, there’s a big question about whether those parents in China fully understood what they signed up for.

By the way, cheating scandals aren’t new (see Vanity Fair’s Schools For Scandal; The Inside Dramas at 16 of America’s Most Elite Campuses—Plus Oxford! Edited by Graydon Carter, published in August 2018 and covering 25 years of the magazine’s reporting). On a similar line, there’s this March13, 2019 essay which picks apart some of the hierarchical and power issues at play in the US higher educational system which led to this latest (but likely not last) scandal.

Scientists under pressure

While Kofler’s February 26, 2019 Nature opinion piece and call to action seems to address the concerns regarding germline editing by advocating that scientists become more conscious of how their choices impact society, as I noted earlier, the ideas expressed seem a little ungrounded in harsh realities. Perhaps it’s time to give some recognition to the various pressures put on scientists from their own governments and from an academic environment that fosters ‘success’ at any cost to peer pressure, etc. (For more about the costs of a science culture focused on success, read this March 2, 2019 blog posting by Jon Tennant on digital-science.com for a breakdown.)

One other thing I should mention, for some scientists getting into the history books, winning Nobel prizes, etc. is a very important goal. Scientists are people too.

Some thoughts

There seems to be a great disjunction between what Richardson presents as an alternative narrative to the ‘gene-god’ and how genetic research is being performed and reported on. What is clear to me is that no one really understands genetics and this business of inserting and deleting genes is essentially research designed to satisfy curiosity and/or allay fears about being left behind in a great scientific race to a an unknown destination.

I’d like to see some better reporting and a more agile response by the scientific community, the various governments, and international agencies. What shape or form a more agile response might take, I don’t know but I’d like to see some efforts.

Back to the regular programme

There’s a lot about CRISPR here on this blog. A simple search of ‘CRISPR ‘in the blog’s search engine should get you more than enough information about the technology and the various issues ranging from intellectual property to risks and more.

The three part series (CRISPR and editing the germline in the US …), mentioned previously, was occasioned by the publication of a study on germline editing research with nonviable embryos in the US. The 2017 research was done at the Oregon Health and Science University by Shoukhrat Mitalipov following similar research published by Chinese scientists in 2015. The series gives relatively complete coverage of the issues along with an introduction to CRISPR and embedded video describing the technique. Here’s part 1 to get you started..