One wouldn’t expect the 97th Canadian Chemistry Conference held in Vancouver, Canada from June 1 – 5, 2014 to be an emotional rollercoaster. One would be wrong. Chemists and members of the art scene are not only different from thee and me, they are different from each other.

Setting the scene

It started with a May 30, 2014 Simon Fraser University (SFU) news release,

During the conference, ProSpect Scientific has arranged for an examination of two Canadian oil paintings; one is an original Lawren Harris (Group of Seven) titled “Hurdy Gurdy” while the other is a painting called “Autumn Harbour” that bears many of Harris’s painting techniques. It was found in Bala, Ontario, an area that was known to have been frequented by Harris.

Using Raman Spectroscopy equipment manufactured by Renishaw (Canada), Dr. Richard Bormett will determine whether the paint from both works of art was painted from the same tube of paint.

As it turns out, the news release got it somewhat wrong. Raman spectroscopy testing does not make it possible to* determine whether the paints came from the same tube, the same batch, or even the same brand. Nonetheless, it is an important tool for art authentication, restoration and/or conservation and both paintings were scheduled for testing on Tuesday, June 3, 2014. But that was not to be.

The owner of the authenticated Harris (Hurdy Gurdy) rescinded permission. No one was sure why but the publication of a June 2, 2014 article by Nick Wells for Metro News Vancouver probably didn’t help in a situation that was already somewhat fraught. The print version of the Wells article titled, “A fraud or a find?” showed only one painting “Hurdy Gurdy” and for anyone reading quickly, it might have seemed that the Hurdy Gurdy painting was the one that could be “a fraud or a find.”

The dramatically titled article no longer seems to be online but there is one (also bylined by Nick Wells) dated June 1, 2014 titled, Chemists in Vancouver to use lasers to verify Group of Seven painting. It features (assuming it is still available online) images of both paintings, the purported Harris (Autumn Harbour) and the authenticated Harris (Hurdy Gurdy),

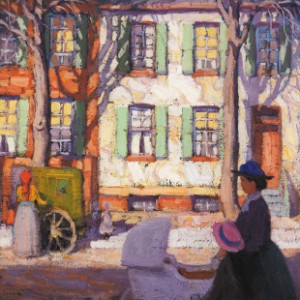

!["Autumn Harbour" [downloaded from http://metronews.ca/news/vancouver/1051693/chemists-in-vancouver-to-use-lasers-to-verify-group-of-seven-painting/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/autumn-harbour-300x198.jpg)

“Autumn Harbour” [downloaded from http://metronews.ca/news/vancouver/1051693/chemists-in-vancouver-to-use-lasers-to-verify-group-of-seven-painting/]

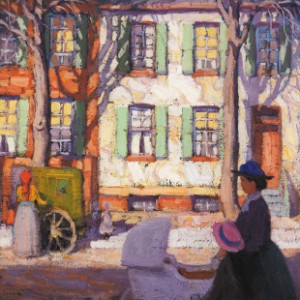

Lawren Harris’‚ Hurdy Gurdy, a depiction of Toronto’s Ward district is shown in this handout image. [downloaded from http://metronews.ca/news/vancouver/1051693/chemists-in-vancouver-to-use-lasers-to-verify-group-of-seven-painting/]

David Robertson who owns the purported Harris (Autumn Harbour) and is an outsider vis à vis the Canadian art world, has been trying to convince people for years that the painting he found in Bala, Ontario is a “Lawren Harris” painting. For anyone unfamiliar with the “

Group of Seven” of which Lawren Harris was a founding member, this group is legendary to many Canadians and is the single most recognized name in Canadian art history (although some might argue that status for Emily Carr and/or Tom Thomson; both of whom have been, on occasion, honorarily included in the Group). Robertson’s incentive to prove “Autumn Harbour” is a Harris could be described as monetary and/or prestige-oriented and/or a desire to make history.

The owner of the authenticated Harris “Hurdy Gurdy” could also be described as an outsider of sorts [unconfirmed at the time of publication; a June 26, 2014 query is outstanding], gaining entry to that select group of people who own a ‘Group of Seven’ painting at a record-setting price in 2012 with the purchase of a piece that has a provenance as close to unimpeachable as you can get. From a Nov. 22, 2012 news item on CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) news online,

Hurdy Gurdy, one of the finest urban landscapes ever painted by Lawren Harris, sold for $1,082,250, a price that includes a 17 per cent buyer’s premium. The pre-sale estimate suggested it could go for $400,000 to $600,000 including the premium.

The Group of Seven founder kept the impressionistic painting of a former Toronto district known as the Ward in his own collection before bequeathing it to his daughter. It has remained in the family ever since.

Occasionally, Harris “would come and say, ‘I need to borrow this back for an exhibition,’ and sometimes she wouldn’t see [the paintings] again,” Heffel vice-president Robert Heffel said. “Harris asked to have this painting back for a show…and she said ‘No, dad. Not this one.’ It was a painting that was very, very dear to her.”

It had been a coup to get access to an authenticated Harris for comparison testing so Hurdy Gurdy’s absence was a major disappointment. Nonetheless, Robertson went through with the scheduled June 3, 2014 testing of his ‘Autumn Harbour’.

Chemistry, spectroscopy, the Raman system, and the experts

Primarily focused on a technical process, the chemists (from ProSpect* Scientific and Renishaw) were unprepared for the drama and excitement that anyone associated with the Canadian art scene might have predicted. From the chemists’ perspective, it was an opportunity to examine a fabled piece of Canadian art (Hurdy Gurdy) and, possibly, play a minor role in making Canadian art history.

The technique the chemists used to examine the purported Harris, Autumn Harbour, is called Raman spectroscopy and its beginnings as a practical technique date back to the 1920s. (You can get more details about Raman spectroscopy in this Wikiipedia entry then will be given here after the spectroscopy description.)

Spectroscopy (borrowing heavily from this Wikipedia entry) is the process where one studies the interaction between matter and radiated energy and which can be measured as frequencies and/or wavelengths. Raman spectroscopy systems can be used to examine radiated energy with low frequency emissions as per this description in the Raman spectroscopy Wikipedia entry,

Raman spectroscopy (/ˈrɑːmən/; named after Sir C. V. Raman) is a spectroscopic technique used to observe vibrational, rotational, and other low-frequency modes in a system.[1] It relies on inelastic scattering, or Raman scattering, of monochromatic light, usually from a laser in the visible, near infrared, or near ultraviolet range. The laser light interacts with molecular vibrations, phonons or other excitations in the system, resulting in the energy of the laser photons being shifted up or down.

The reason for using Raman spectroscopy for art authentication, conservation, and/or restoration purposes is that the technique, as noted earlier, can specify the specific chemical composition of the pigments used to create the painting. It is a technique used in many fields as a representative from ProSpect Scientific notes,

Raman spectroscopy is a vital tool for minerologists, forensic investigators, surface science development, nanotechnology research, pharmaceutical research and other applications. Most graduate level university labs have this technology today, as do many government and industry researchers. Raman spectroscopy is now increasingly available in single purpose hand held units that can identify the presence of a small number of target substances with ease-of-use appropriate for field work by law enforcers, first responders or researchers in the field.

About the chemists and ProSpect Scientific and Renishaw

There were two technical experts attending the June 3, 2014 test for the purported Harris painting, Autumn Harbour, Dr. Richard Bormett of Renishaw and Dr. Kelly Akers of ProSpect Scientific.

Dr. Kelly Akers founded ProSpect Scientific in 1996. Her company represents Renishaw Raman spectroscopy systems for the most part although other products are also represented throughout North America. Akers’ company is located in Orangeville, Ontario. Renishaw, a company based in the UK. offers a wide line of products including Raman spectroscopes. (There is a Renishaw Canada Ltd., headquartered in Mississauga, Ontario, representing products other than Raman spectroscopes.)

ProSpect Scientific runs Raman spectroscopy workshops, at the Canadian Chemistry Conferences as a regular occurrence, often in conjunction with Renishaw’s Bormett,. David Robertson, on learning the company would be at the 2014 Canadian Chemistry Conference in Vancouver, contacted Akers and arranged to have his purported Harris and Hurdy Gurdy, the authenticated Harris, tested at the conference.

Bormett, based in Chicago, Illinois, is Renishaw’s business manager for the Spectroscopy Products Division in North America (Canada, US, & Mexico). His expertise as a spectroscopist has led him to work with many customers throughout the Americas and, as such, has worked with several art institutions and museums on important and valuable artifacts. He has wide empirical knowledge of Raman spectra for many things, including pigments, but does not claim expertise in art or art authentication. You can hear him speak at a 2013 US Library of Congress panel discussion titled, “Advances in Raman Spectroscopy for Analysis of Cultural Heritage Materials,” part of the Library of Congress’s Topics in Preservation Series (TOPS), here on the Library of Congress website or here on YouTube. The discussion runs some 130 minutes.

Bormett has a PhD in analytical chemistry from the University of Pittsburgh. Akers has a PhD in physical chemistry from the University of Toronto and is well known in the Raman spectroscopy field having published in many refereed journals including “Science” and the “Journal of Physical Chemistry.” She expanded her knowledge of industrial applications of Raman spectroscopy substantive post doctoral work in Devon, Alberta at the CANMET Laboratory (Natural Resources Canada).

About Renishaw InVia Reflex Raman Spectrometers

The Raman spectroscopy system used for the examination, a Renishaw InVia Reflex Raman Spectrometer, had

- two lasers (using 785nm [nanometres] and 532nm lasers for this application),

- two cameras,

(ProSpect Scientific provided this description of the cameras: The system has one CCD [Charged Coupled Device] camera that collects the scattered laser light to produce Raman spectra [very sensitive and expensive]. The system also has a viewing camera mounted on the microscope to allow the user to visually see what the target spot on the sample looks like. This camera shows on the computer what is visible through the eyepieces of the microscope.)

- a microscope,

- and a computer with a screen,

all of which fit on a tabletop, albeit a rather large one.

For anyone unfamiliar with the term CCD (charged coupled device), it is a sensor used in cameras to capture light and convert it to digital data for capture by the camera. (You can find out more here at TechTerms.com on the CCD webpage.)

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

* ‘to’ added to sentence on June 27, 2014 at 1340 hours (PDT). ‘ProsPect’ corrected to ‘ProSpect’ on June 30, 2014.

ETA July 14, 2014 at 1300 hours PDT: There is now an addendum to this series, which features a reply from the Canadian Conservation Institute to a query about art pigments used by Canadian artists and access to a database of information about them.

Lawren Harris (Group of Seven), art authentication, and the Canadian Conservation Insitute (addendum to four-part series)

!["Autumn Harbour" [downloaded from http://metronews.ca/news/vancouver/1051693/chemists-in-vancouver-to-use-lasers-to-verify-group-of-seven-painting/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/autumn-harbour-300x198.jpg)