An August 30, 2018 news item on Nanowerk announces the report,

The monitoring of air contamination by engineered nanomaterials (ENM) is a complex process with many uncertainties and limitations owing to the presence of particles of nanometric size that are not ENMs, the lack of validated instruments for breathing zone measurements and the many indicators to be considered.

In addition, some organizations, France’s Institut national de recherche et de sécurité (INRS) and Québec’s Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail (IRSST) among them, stress the need to also sample surfaces for ENM deposits.

In other words, to get a better picture of the risks of worker exposure, we need to fine-tune the existing methods of sampling and characterizing ENMs and develop new one. Accordingly, the main goal of this project was to develop innovative methodological approaches for detailed qualitative as well as quantitative characterization of workplace exposure to ENMs.

A PDF of the 88-page report is available in English or in French.

An August 30, 2018 (?) abstract of the IRSST report titled An Assessment of Methods of Sampling and Characterizing Engineered Nanomaterials in the Air and on Surfaces in the Workplace (2nd edition) by Maximilien Debia, Gilles L’Espérance, Cyril Catto, Philippe Plamondon, André Dufresne, Claude Ostiguy, which originated the news item, outlines what you can expect from the report,

This research project has two complementary parts: a laboratory investigation and a fieldwork component. The laboratory investigation involved generating titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles under controlled laboratory conditions and studying different sampling and analysis devices. The fieldwork comprised a series of nine interventions adapted to different workplaces and designed to test a variety of sampling devices and analytical procedures and to measure ENM exposure levels among Québec workers.

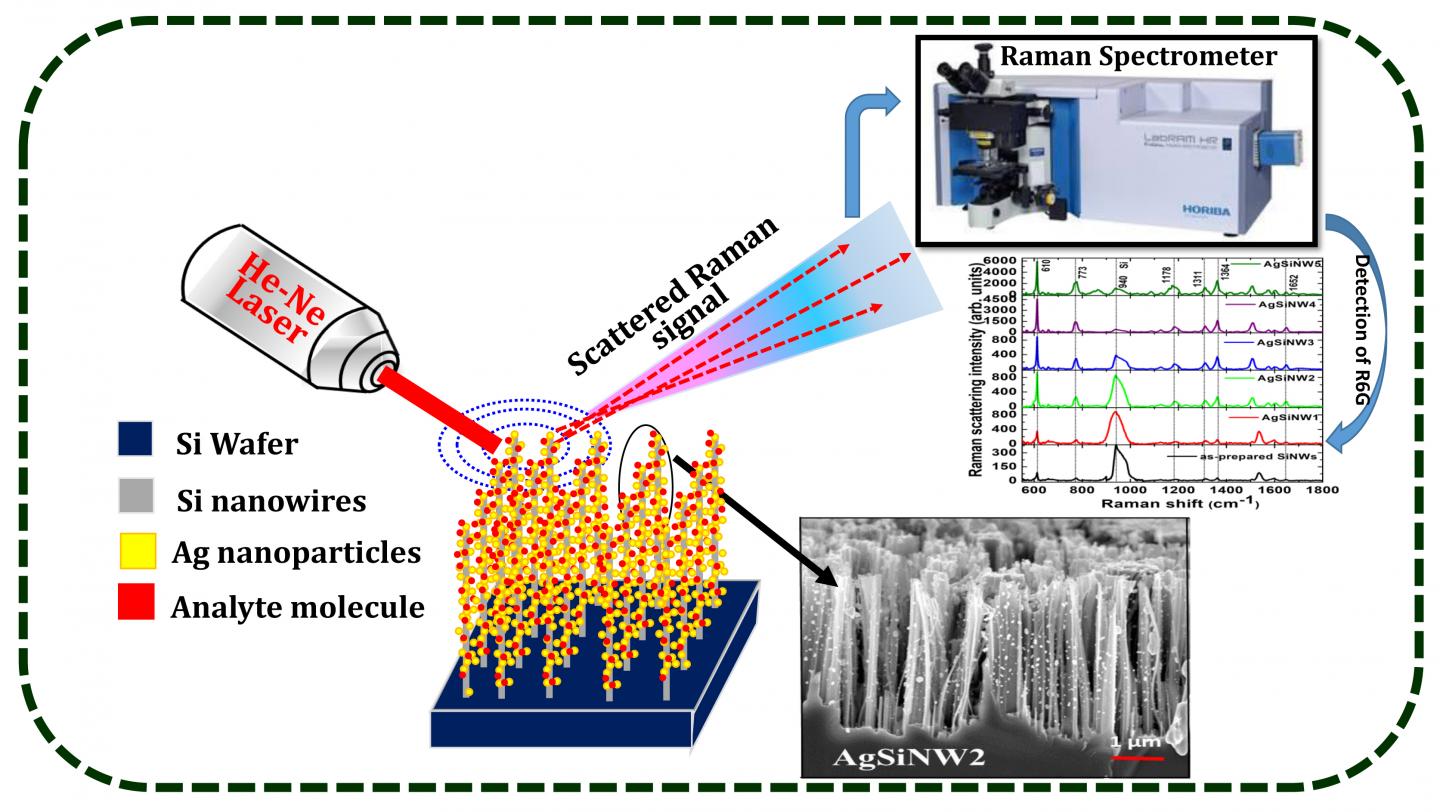

The methods for characterizing aerosols and surface deposits that were investigated include: i) measurement by direct-reading instruments (DRI), such as condensation particle counters (CPC), optical particle counters (OPC), laser photometers, aerodynamic diameter spectrometers and electric mobility spectrometer; ii) transmission electron microscopy (TEM) or scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) with a variety of sampling devices, including the Mini Particle Sampler® (MPS); iii) measurement of elemental carbon (EC); iv) inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and (v) Raman spectroscopy.

The workplace investigations covered a variety of industries (e.g., electronics, manufacturing, printing, construction, energy, research and development) and included producers as well as users or integrators of ENMs. In the workplaces investigated, we found nanometals or metal oxides (TiO2, SiO2, zinc oxides, lithium iron phosphate, titanate, copper oxides), nanoclays, nanocellulose and carbonaceous materials, including carbon nanofibers (CNF) and carbon nanotubes (CNT)—single-walled (SWCNT) as well as multiwalled (MWCNT).

The project helped to advance our knowledge of workplace assessments of ENMs by documenting specific tasks and industrial processes (e.g., printing and varnishing) as well as certain as yet little investigated ENMs (nanocellulose, for example).

Based on our investigations, we propose a strategy for more accurate assessment of ENM exposure using methods that require a minimum of preanalytical handling. The recommended strategy is a systematic two-step assessment of workplaces that produce and use ENMs. The first step involves testing with different DRIs (such as a CPC and a laser photometer) as well as sample collection and subsequent microscopic analysis (MPS + TEM/STEM) to clearly identify the work tasks that generate ENMs. The second step, once work exposure is confirmed, is specific quantification of the ENMs detected. The following findings are particularly helpful for detailed characterization of ENM exposure:

- The first conclusive tests of a technique using ICP-MS to quantify the metal oxide content of samples collected in the workplace

- The possibility of combining different sampling methods recommended by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) to measure elemental carbon as an indicator of NTC/NFC, as well as demonstration of the limitation of this method stemming from observed interference with the black carbon particles required to synthesis carbon materials (for example, Raman spectroscopy showed that less than 6% of the particles deposited on the electron microscopy grid at one site were SWCNTs)

- The clear advantages of using an MPS (instead of the standard 37-mm cassettes used as sampling media for electron microscopy), which allows quantification of materials

- The major impact of sampling time: a long sampling time overloads electron microscopy grids and can lead to overestimation of average particle agglomerate size and underestimation of particle concentrations

- The feasibility and utility of surface sampling, either with sampling pumps or passively by diffusion onto the electron microscopy grids, to assess ENM dispersion in the workplace

These original findings suggest promising avenues for assessing ENM exposure, while also showing their limitations. Improvements to our sampling and analysis methods give us a better understanding of ENM exposure and help in adapting and implementing control measures that can minimize occupational exposure.

You can download the full report in either or both English and French from the ‘Nanomaterials – A Guide to Good Practices Facilitating Risk Management in the Workplace, 2nd Edition‘ webpage.