Dear friend,

I thought it best to break this up a bit. There are a couple of ‘objects’ still to be discussed but this is mostly the commentary part of this letter to you. (Here’s a link for anyone who stumbled here but missed Part 1.)

Ethics, the natural world, social justice, eeek, and AI

Dorothy Woodend in her March 10, 2022 review for The Tyee) suggests some ethical issues in her critique of the ‘bee/AI collaboration’ and she’s not the only one with concerns. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) has produced global recommendations for ethical AI (see my March 18, 2022 posting). More recently, there’s “Racist and sexist robots have flawed AI,” a June 23, 2022 posting, where researchers prepared a conference presentation and paper about deeply flawed AI still being used in robots.

Ultimately, the focus is always on humans and Woodend has extended the ethical AI conversation to include insects and the natural world. In short, something less human-centric.

My friend, this reference to the de Young exhibit may seem off topic but I promise it isn’t in more ways than one. The de Young Museum in San Francisco (February 22, 2020 – June 27, 2021) also held and AI and art show called, “Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI”), from the exhibitions page,

In today’s AI-driven world, increasingly organized and shaped by algorithms that track, collect, and evaluate our data, the question of what it means to be human [emphasis mine] has shifted. Uncanny Valley is the first major exhibition to unpack this question through a lens of contemporary art and propose new ways of thinking about intelligence, nature, and artifice. [emphasis mine]

As you can see, it hinted (perhaps?) at an attempt to see beyond human-centric AI. (BTW, I featured this ‘Uncanny Valley’ show in my February 25, 2020 posting where I mentioned Stephanie Dinkins [featured below] and other artists.)

Social justice

While the VAG show doesn’t see much past humans and AI, it does touch on social justice. In particular there’s Pod 15 featuring the Algorithmic Justice League (AJL). The group “combine[s] art and research to illuminate the social implications and harms of AI” as per their website’s homepage.

In Pod 9, Stephanie Dinkins’ video work with a robot (Bina48), which was also part of the de Young Museum ‘Uncanny Valley’ show, addresses some of the same issues.

From the the de Young Museum’s Stephanie Dinkins “Conversations with Bina48” April 23, 2020 article by Janna Keegan (Dinkins submitted the same work you see at the VAG show), Note: Links have been removed,

Transdisciplinary artist and educator Stephanie Dinkins is concerned with fostering AI literacy. The central thesis of her social practice is that AI, the internet, and other data-based technologies disproportionately impact people of color, LGBTQ+ people, women, and disabled and economically disadvantaged communities—groups rarely given a voice in tech’s creation. Dinkins strives to forge a more equitable techno-future by generating AI that includes the voices of multiple constituencies …

The artist’s ongoing Conversations with Bina48 takes the form of a series of interactions with the social robot Bina48 (Breakthrough Intelligence via Neural Architecture, 48 exaflops per second). The machine is the brainchild of Martine Rothblatt, an entrepreneur in the field of biopharmaceuticals who, with her wife, Bina, cofounded the Terasem Movement, an organization that seeks to extend human life through cybernetic means. In 2007 Martine commissioned Hanson Robotics to create a robot whose appearance and consciousness simulate Bina’s. The robot was released in 2010, and Dinkins began her work with it in 2014.

…

Part psychoanalytical discourse, part Turing test, Conversations with Bina48 also participates in a larger dialogue regarding bias and representation in technology. Although Bina Rothblatt is a Black woman, Bina48 was not programmed with an understanding of its Black female identity or with knowledge of Black history. Dinkins’s work situates this omission amid the larger tech industry’s lack of diversity, drawing attention to the problems that arise when a roughly homogenous population creates technologies deployed globally. When this occurs, writes art critic Tess Thackara, “the unconscious biases of white developers proliferate on the internet, mapping our social structures and behaviors onto code and repeating imbalances and injustices that exist in the real world.” One of the most appalling and public of these instances occurred when a Google Photos image-recognition algorithm mislabeled the faces of Black people as “gorillas.”

…

Eeek

You will find as you go through the ‘imitation game’ a pod with a screen showing your movements through the rooms in realtime on a screen. The installation is called “Creepers” (2021-22). The student team from Vancouver’s Centre for Digital Media (CDM) describes their project this way, from the CDM’s AI-driven Installation Piece for the Vancouver Art Gallery webpage,

Project Description

Kaleidoscope [team name] is designing an installation piece that harnesses AI to collect and visualize exhibit visitor behaviours, and interactions with art, in an impactful and thought-provoking way.

There’s no warning that you’re being tracked and you can see they’ve used facial recognition software to track your movements through the show. It’s claimed on the pod’s signage that they are deleting the data once you’ve left.

‘Creepers’ is an interesting approach to the ethics of AI. The name suggests that even the student designers were aware it was problematic.

For the curious, there’s a description of the other VAG ‘imitation game’ installations provided by CDM students on the ‘Master of Digital Media Students Develop Revolutionary Installations for Vancouver Art Gallery AI Exhibition‘ webpage.

In recovery from an existential crisis (meditations)

There’s something greatly ambitious about “The Imitation Game: Visual Culture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence” and walking up the VAG’s grand staircase affirms that ambition. Bravo to the two curators, Grenville and Entis for an exhibition.that presents a survey (or overview) of artificial intelligence, and its use in and impact on creative visual culture.

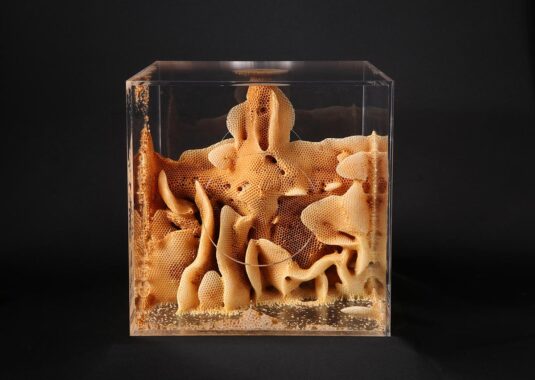

I’ve already enthused over the history (specifically Turing, Lovelace, Ovid), admitted to being mesmerized by Scott Eaton’s sculpture/AI videos, and confessed to a fascination (and mild repulsion) regarding Oxman’s honeycombs.

It’s hard to remember all of the ‘objects’ as the curators have offered a jumble of work, almost all of them on screens. Already noted, there’s Norbert Wiener’s The Moth (1949) and there are also a number of other computer-based artworks from the 1960s and 1970s. Plus, you’ll find works utilizing a GAN (generative adversarial network), an AI agent that is explained in the exhibit.

It’s worth going more than once to the show as there is so much to experience.

Why did they do that?

Dear friend, I’ve already commented on the poor flow through the show and It’s hard to tell if the curators intended the experience to be disorienting but this is to the point of chaos, especially when the exhibition is crowded.

I’ve seen Grenville’s shows before. In particular there was “MashUp: The Birth of Modern Culture, a massive survey documenting the emergence of a mode of creativity that materialized in the late 1800s and has grown to become the dominant model of cultural production in the 21st century” and there was “KRAZY! The Delirious World of Anime + Manga + Video Games + Art.” As you can see from the description, he pulls together disparate works and ideas into a show for you to ‘make sense’ of them.

One of the differences between those shows and the “imitation Game: …” is that most of us have some familiarity, whether we like it or not, with modern art/culture and anime/manga/etc. and can try to ‘make sense’ of it.

By contrast, artificial intelligence (which even experts have difficulty defining) occupies an entirely different set of categories; all of them associated with science/technology. This makes for a different kind of show so the curators cannot rely on the audience’s understanding of basics. It’s effectively an art/sci or art/tech show and, I believe, the first of its kind at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Unfortunately, the curators don’t seem to have changed their approach to accommodate that difference.

AI is also at the centre of a current panic over job loss, loss of personal agency, automated racism and sexism, etc. which makes the experience of viewing the show a little tense. In this context, their decision to commission and use ‘Creepers’ seems odd.

Where were Ai-Da and Dall-E-2 and the others?

Oh friend, I was hoping for a robot. Those roomba paintbots didn’t do much for me. All they did was lie there on the floor

To be blunt I wanted some fun and perhaps a bit of wonder and maybe a little vitality. I wasn’t necessarily expecting Ai-Da, an artisitic robot, but something three dimensional and fun in this very flat, screen-oriented show would have been nice.

Ai-Da was first featured here in a December 17, 2021 posting about performing poetry that she had written in honour of the 700th anniversary of poet Dante Alighieri’s death.

Named in honour of Ada Lovelace, Ai-Da visited the 2022 Venice Biennale as Leah Henrickson and Simone Natale describe in their May 12, 2022 article for Fast Company (Note: Links have been removed),

Ai-Da sits behind a desk, paintbrush in hand. She looks up at the person posing for her, and then back down as she dabs another blob of paint onto the canvas. A lifelike portrait is taking shape. If you didn’t know a robot produced it, this portrait could pass as the work of a human artist.

Ai-Da is touted as the “first robot to paint like an artist,” and an exhibition of her work, called Leaping into the Metaverse, opened at the Venice Biennale.

Ai-Da produces portraits of sitting subjects using a robotic hand attached to her lifelike feminine figure. She’s also able to talk, giving detailed answers to questions about her artistic process and attitudes toward technology. She even gave a TEDx talk about “The Intersection of Art and AI” in Oxford a few years ago. While the words she speaks are programmed, Ai-Da’s creators have also been experimenting with having her write and perform her own poetry.

…

She has her own website.

If not Ai-Da, what about Dall-E-2? Aaron Hertzmann’s June 20, 2022 commentary, “Give this AI a few words of description and it produces a stunning image – but is it art?” investigates for Salon (Note: Links have been removed),

…

DALL-E 2 is a new neural network [AI] algorithm that creates a picture from a short phrase or sentence that you provide. The program, which was announced by the artificial intelligence research laboratory OpenAI in April 2022, hasn’t been released to the public. But a small and growing number of people – myself included – have been given access to experiment with it.

As a researcher studying the nexus of technology and art, I was keen to see how well the program worked. After hours of experimentation, it’s clear that DALL-E – while not without shortcomings – is leaps and bounds ahead of existing image generation technology. It raises immediate questions about how these technologies will change how art is made and consumed. It also raises questions about what it means to be creative when DALL-E 2 seems to automate so much of the creative process itself.

…

A July 4, 2022 article “DALL-E, Make Me Another Picasso, Please” by Laura Lane for The New Yorker has a rebuttal to Ada Lovelace’s contention that creativity is uniquely human (Note: A link has been removed),

…

“There was this belief that creativity is this deeply special, only-human thing,” Sam Altman, OpenAI’s C.E.O., explained the other day. Maybe not so true anymore, he said. Altman, who wore a gray sweater and had tousled brown hair, was videoconferencing from the company’s headquarters, in San Francisco. DALL-E is still in a testing phase. So far, OpenAI has granted access to a select group of people—researchers, artists, developers—who have used it to produce a wide array of images: photorealistic animals, bizarre mashups, punny collages. Asked by a user to generate “a plate of various alien fruits from another planet photograph,” DALL-E returned something kind of like rambutans. “The rest of mona lisa” is, according to DALL-E, mostly just one big cliff. Altman described DALL-E as “an extension of your own creativity.”

…

There are other AI artists, in my August 16, 2019 posting, I had this,

AI artists first hit my radar in August 2018 when Christie’s Auction House advertised an art auction of a ‘painting’ by an algorithm (artificial intelligence). There’s more in my August 31, 2018 posting but, briefly, a French art collective, Obvious, submitted a painting, “Portrait of Edmond de Belamy,” that was created by an artificial intelligence agent to be sold for an estimated to $7000 – $10,000. They weren’t even close. According to Ian Bogost’s March 6, 2019 article for The Atlantic, the painting sold for $432,500 In October 2018.

…

That posting also included AI artist, AICAN. Both artist-AI agents (Obvious and AICAN) are based on GANs (generative adversarial networks) for learning and eventual output. Both artist-AI agents work independently or with human collaborators on art works that are available for purchase.

As might be expected not everyone is excited about AI and visual art. Sonja Drimmer, Professor of Medieval Art, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, provides another perspective on AI, visual art, and, her specialty, art history in her November 1, 2021 essay for The Conversation (Note: Links have been removed),

Over the past year alone, I’ve come across articles highlighting how artificial intelligence recovered a “secret” painting of a “lost lover” of Italian painter Modigliani, “brought to life” a “hidden Picasso nude”, “resurrected” Austrian painter Gustav Klimt’s destroyed works and “restored” portions of Rembrandt’s 1642 painting “The Night Watch.” The list goes on.

As an art historian, I’ve become increasingly concerned about the coverage and circulation of these projects.

They have not, in actuality, revealed one secret or solved a single mystery.

What they have done is generate feel-good stories about AI.

…

Take the reports about the Modigliani and Picasso paintings.

These were projects executed by the same company, Oxia Palus, which was founded not by art historians but by doctoral students in machine learning.

In both cases, Oxia Palus relied upon traditional X-rays, X-ray fluorescence and infrared imaging that had already been carried out and published years prior – work that had revealed preliminary paintings beneath the visible layer on the artists’ canvases.

The company edited these X-rays and reconstituted them as new works of art by applying a technique called “neural style transfer.” This is a sophisticated-sounding term for a program that breaks works of art down into extremely small units, extrapolates a style from them and then promises to recreate images of other content in that same style.

…

As you can ‘see’ my friend, the topic of AI and visual art is a juicy one. In fact, I have another example in my June 27, 2022 posting, which is titled, “Art appraised by algorithm.” So, Grenville’s and Entis’ decision to focus on AI and its impact on visual culture is quite timely.

Visual culture: seeing into the future

The VAG Imitation Game webpage lists these categories of visual culture “animation, architecture, art, fashion, graphic design, urban design and video games …” as being represented in the show. Movies and visual art, not mentioned in the write up, are represented while theatre and other performing arts are not mentioned or represented. That’ s not a surprise.

In addition to an area of science/technology that’s not well understood even by experts, the curators took on the truly amorphous (and overwhelming) topic of visual culture. Given that even writing this commentary has been a challenge, I imagine pulling the show together was quite the task.

Grenville often grounds his shows in a history of the subject and, this time, it seems especially striking. You’re in a building that is effectively a 19th century construct and in galleries that reflect a 20th century ‘white cube’ aesthetic, while looking for clues into the 21st century future of visual culture employing technology that has its roots in the 19th century and, to some extent, began to flower in the mid-20th century.

Chung’s collaboration is one of the only ‘optimistic’ notes about the future and, as noted earlier, it bears a resemblance to Wiener’s 1949 ‘Moth’

Overall, it seems we are being cautioned about the future. For example, Oxman’s work seems bleak (bees with no flowers to pollinate and living in an eternal spring). Adding in ‘Creepers’ and surveillance along with issues of bias and social injustice reflects hesitation and concern about what we will see, who sees it, and how it will be represented visually.

Learning about robots, automatons, artificial intelligence, and more

I wish the Vancouver Art Gallery (and Vancouver’s other art galleries) would invest a little more in audience education. A couple of tours, by someone who may or may not know what they’re talking, about during the week do not suffice. The extra material about Stephanie Dinkins and her work (“Conversations with Bina48,” 2014–present) came from the de Young Museum’s website. In my July 26, 2021 commentary on North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery 2021 show “Interior Infinite,” I found background information for artist Zanele Muholi on the Tate Modern’s website. There is nothing on the VAG website that helps you to gain some perspective on the artists’ works.

It seems to me that if the VAG wants to be considered world class, it should conduct itself accordingly and beefing up its website with background information about their current shows would be a good place to start.

Robots, automata, and artificial intelligence

Prior to 1921, robots were known exclusively as automatons. These days, the word ‘automaton’ (or ‘automata’ in the plural) seems to be used to describe purely mechanical representations of humans from over 100 years ago whereas the word ‘robot’ can be either ‘humanlike’ or purely machine, e.g. a mechanical arm that performs the same function over and over. I have a good February 24, 2017 essay on automatons by Miguel Barral for OpenMind BBVA*, which provides some insight into the matter,

The concept of robot is relatively recent. The idea was introduced in 1921 by the Czech writer Karel Capek in his work R.U.R to designate a machine that performs tasks in place of man. But their predecessors, the automatons (from the Greek automata, or “mechanical device that works by itself”), have been the object of desire and fascination since antiquity. Some of the greatest inventors in history, such as Leonardo Da Vinci, have contributed to our fascination with these fabulous creations:

The Al-Jazari automatons

The earliest examples of known automatons appeared in the Islamic world in the 12th and 13th centuries. In 1206, the Arab polymath Al-Jazari, whose creations were known for their sophistication, described some of his most notable automatons: an automatic wine dispenser, a soap and towels dispenser and an orchestra-automaton that operated by the force of water. This latter invention was meant to liven up parties and banquets with music while floating on a pond, lake or fountain.

As the water flowed, it started a rotating drum with pegs that, in turn, moved levers whose movement produced different sounds and movements. As the pegs responsible for the musical notes could be exchanged for different ones in order to interpret another melody, it is considered one of the first programmable machines in history.

…

If you’re curious about automata, my friend, I found this Sept. 26, 2016 ABC news radio news item about singer Roger Daltrey’s and his wife, Heather’s auction of their collection of 19th century French automata (there’s an embedded video showcasing these extraordinary works of art). For more about automata, robots, and androids, there’s an excellent May 4, 2022 article by James Vincent, ‘A visit to the human factory; How to build the world’s most realistic robot‘ for The Verge; Vincent’s article is about Engineered Arts, the UK-based company that built Ai-Da.

AI is often used interchangeably with ‘robot’ but they aren’t the same. Not all robots have AI integrated into their processes. At its simplest AI is an algorithm or set of algorithms, which may ‘live’ in a CPU and be effectively invisible or ‘live’ in or make use of some kind of machine and/or humanlike body. As the experts have noted, the concept of artificial intelligence is a slippery concept.

*OpenMind BBVA is a Spanish multinational financial services company, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA), which runs the non-profit project, OpenMind (About us page) to disseminate information on robotics and so much more.*

You can’t always get what you want

My friend,

I expect many of the show’s shortcomings (as perceived by me) are due to money and/or scheduling issues. For example, Ai-Da was at the Venice Biennale and if there was a choice between the VAG and Biennale, I know where I’d be.

Even with those caveats in mind, It is a bit surprising that there were no examples of wearable technology. For example, Toronto’s Tapestry Opera recently performed R.U.R. A Torrent of Light (based on the word ‘robot’ from Karel Čapek’s play, R.U.R., ‘Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti’), from my May 24, 2022 posting,

I have more about tickets prices, dates, and location later in this post but first, here’s more about the opera and the people who’ve created it from the Tapestry Opera’s ‘R.U.R. A Torrent of Light’ performance webpage,

“This stunning new opera combines dance, beautiful multimedia design, a chamber orchestra including 100 instruments creating a unique electronica-classical sound, and wearable technology [emphasis mine] created with OCAD University’s Social Body Lab, to create an immersive and unforgettable science-fiction experience.”

And, from later in my posting,

“Despite current stereotypes, opera was historically a launchpad for all kinds of applied design technologies. [emphasis mine] Having the opportunity to collaborate with OCAD U faculty is an invigorating way to reconnect to that tradition and foster connections between art, music and design, [emphasis mine]” comments the production’s Director Michael Hidetoshi Mori, who is also Tapestry Opera’s Artistic Director.

That last quote brings me back to the my comment about theatre and performing arts not being part of the show. Of course, the curators couldn’t do it all but a website with my hoped for background and additional information could have helped to solve the problem.

The absence of the theatrical and performing arts in the VAG’s ‘Imitation Game’ is a bit surprising as the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA) in their third assessment, “Competing in a Global Innovation Economy: The Current State of R&D in Canada” released in 2018 noted this (from my April 12, 2018 posting),

Canada, relative to the world, specializes in subjects generally referred to as the

humanities and social sciences (plus health and the environment), and does

not specialize as much as others in areas traditionally referred to as the physical

sciences and engineering. Specifically, Canada has comparatively high levels

of research output in Psychology and Cognitive Sciences, Public Health and

Health Services, Philosophy and Theology, Earth and Environmental Sciences,

and Visual and Performing Arts. [emphasis mine] It accounts for more than 5% of world research in these fields. Conversely, Canada has lower research output than expected in Chemistry, Physics and Astronomy, Enabling and Strategic Technologies,

Engineering, and Mathematics and Statistics. The comparatively low research

output in core areas of the natural sciences and engineering is concerning,

and could impair the flexibility of Canada’s research base, preventing research

institutions and researchers from being able to pivot to tomorrow’s emerging

research areas. [p. xix Print; p. 21 PDF]

US-centric

My friend,

I was a little surprised that the show was so centered on work from the US given that Grenville has curated ate least one show where there was significant input from artists based in Asia. Both Japan and Korea are very active with regard to artificial intelligence and it’s hard to believe that their artists haven’t kept pace. (I’m not as familiar with China and its AI efforts, other than in the field of facial recognition, but it’s hard to believe their artists aren’t experimenting.)

The Americans, of course, are very important developers in the field of AI but they are not alone and it would have been nice to have seen something from Asia and/or Africa and/or something from one of the other Americas. In fact, anything which takes us out of the same old, same old. (Luba Elliott wrote this (2019/2020/2021?) essay, “Artificial Intelligence Art from Africa and Black Communities Worldwide” on Aya Data if you want to get a sense of some of the activity on the African continent. Elliott does seem to conflate Africa and Black Communities, for some clarity you may want to check out the Wikipedia entry on Africanfuturism, which contrasts with this August 12, 2020 essay by Donald Maloba, “What is Afrofuturism? A Beginner’s Guide.” Maloba also conflates the two.)

As it turns out, Luba Elliott presented at the 2019 Montréal Digital Spring event, which brings me to Canada’s artificial intelligence and arts scene.

I promise I haven’t turned into a flag waving zealot, my friend. It’s just odd there isn’t a bit more given that machine learning was pioneered at the University of Toronto. Here’s more about that (from Wikipedia entry for Geoffrey Hinston),

Geoffrey Everest HintonCCFRSFRSC[11] (born 6 December 1947) is a British-Canadian cognitive psychologist and computer scientist, most noted for his work on artificial neural networks.

…

Hinton received the 2018 Turing Award, together with Yoshua Bengio [Canadian scientist] and Yann LeCun, for their work on deep learning.[24] They are sometimes referred to as the “Godfathers of AI” and “Godfathers of Deep Learning“,[25][26] and have continued to give public talks together.[27][28]

…

Some of Hinton’s work was started in the US but since 1987, he has pursued his interests at the University of Toronto. He wasn’t proven right until 2012. Katrina Onstad’s February 29, 2018 article (Mr. Robot) for Toronto Life is a gripping read about Hinton and his work on neural networks. BTW, Yoshua Bengio (co-Godfather) is a Canadian scientist at the Université de Montréal and Yann LeCun (co-Godfather) is a French scientist at New York University.

Then, there’s another contribution, our government was the first in the world to develop a national artificial intelligence strategy. Adding those developments to the CCA ‘State of Science’ report findings about visual arts and performing arts, is there another word besides ‘odd’ to describe the lack of Canadian voices?

You’re going to point out the installation by Ben Bogart (a member of Simon Fraser University’s Metacreation Lab for Creative AI and instructor at the Emily Carr University of Art + Design (ECU)) but it’s based on the iconic US scifi film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. As for the other Canadian, Sougwen Chung, she left Canada pretty quickly to get her undergraduate degree in the US and has since moved to the UK. (You could describe hers as the quintessential success story, i.e., moving from Canada only to get noticed here after success elsewhere.)

Of course, there are the CDM student projects but the projects seem less like an exploration of visual culture than an exploration of technology and industry requirements, from the ‘Master of Digital Media Students Develop Revolutionary Installations for Vancouver Art Gallery AI Exhibition‘ webpage, Note: A link has been removed,

…

In 2019, Bruce Grenville, Senior Curator at Vancouver Art Gallery, approached [the] Centre for Digital Media to collaborate on several industry projects for the forthcoming exhibition. Four student teams tackled the project briefs over the course of the next two years and produced award-winning installations that are on display until October 23 [2022].

…

Basically, my friend, it would have been nice to see other voices or, at the least, an attempt at representing other voices and visual cultures informed by AI. As for Canadian contributions, maybe put something on the VAG website?

Playing well with others

it’s always a mystery to me why the Vancouver cultural scene seems comprised of a set of silos or closely guarded kingdoms. Reaching out to the public library and other institutions such as Science World might have cost time but could have enhanced the show

For example, one of the branches of the New York Public Library ran a programme called, “We are AI” in March 2022 (see my March 23, 2022 posting about the five-week course, which was run as a learning circle). The course materials are available for free (We are AI webpage) and I imagine that adding a ‘visual culture module’ wouldn’t be that difficult.

There is one (rare) example of some Vancouver cultural institutions getting together to offer an art/science programme and that was in 2017 when the Morris and Helen Belkin Gallery (at the University of British Columbia; UBC) hosted an exhibition of Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s work (see my Sept. 11, 2017 posting about the gallery show) along with that show was an ancillary event held by the folks at Café Scientifique at Science World and featuring a panel of professionals from UBC’s Faculty of Medicine and Dept. of Psychology, discussing Cajal’s work.

In fact, where were the science and technology communities for this show?

On a related note, the 2022 ACM SIGGRAPH conference (August 7 – 11, 2022) is being held in Vancouver. (ACM is the Association for Computing Machinery; SIGGRAPH is for Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques.) SIGGRAPH has been holding conferences in Vancouver every few years since at least 2011.

At this year’s conference, they have at least two sessions that indicate interests similar to the VAG’s. First, there’s Immersive Visualization for Research, Science and Art which includes AI and machine learning along with other related topics. There’s also, Frontiers Talk: Art in the Age of AI: Can Computers Create Art?

This is both an international conference and an exhibition (of art) and the whole thing seems to have kicked off on July 25, 2022. If you’re interested, the programme can be found here and registration here.

Last time SIGGRAPH was here the organizers seemed interested in outreach and they offered some free events.

In the end

It was good to see the show. The curators brought together some exciting material. As is always the case, there were some missed opportunities and a few blind spots. But all is not lost.

July 27, 2022, the VAG held a virtual event with an artist,

… Gwenyth Chao to learn more about what happened to the honeybees and hives in Oxman’s Synthetic Apiary project. As a transdisciplinary artist herself, Chao will also discuss the relationship between art, science, technology and design. She will then guide participants to create a space (of any scale, from insect to human) inspired by patterns found in nature.

Hopefully there will be more more events inspired by specific ‘objects’. Meanwhile, August 12, 2022, the VAG is hosting,

… in partnership with the Canadian Music Centre BC, New Music at the Gallery is a live concert series hosted by the Vancouver Art Gallery that features an array of musicians and composers who draw on contemporary art themes.

Highlighting a selection of twentieth- and twenty-first-century music compositions, this second concert, inspired by the exhibition The Imitation Game: Visual Culture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, will spotlight The Iliac Suite (1957), the first piece ever written using only a computer, and Kaija Saariaho’s Terra Memoria (2006), which is in a large part dependent on a computer-generated musical process.

…

It would be lovely if they could include an Ada Lovelace Day event. This is an international celebration held on October 11, 2022.

Do go. Do enjoy, my friend.

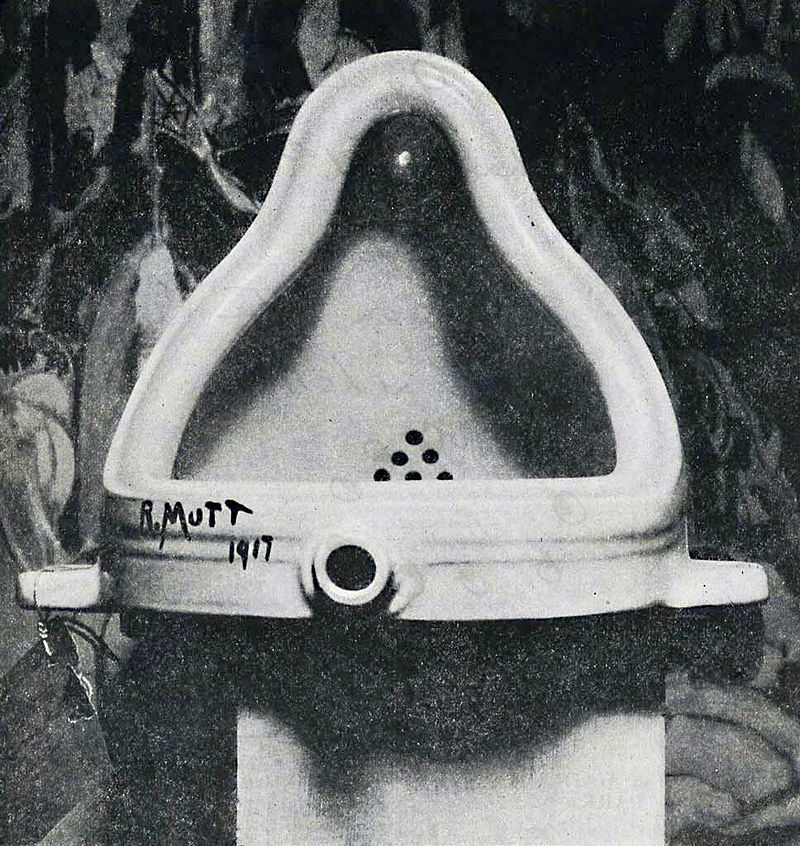

![The original Fountain by Marcel Duchamp photographed by Alfred Stieglitz at the 291 (Art Gallery) after the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibit. Stieglitz used a backdrop of The Warriors by Marsden Hartley to photograph the urinal. The entry tag is clearly visible. [downloaded from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fountain_%28Duchamp%29]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/MarcelDuchampsUrinal.jpg)

![Lawrence Bonassar, associate professor of biomedical engineering, and colleagues collaborated with Weill Cornell Medical College physicians to create an artificial ear using 3-D printing and injectable molds. Credit: Lindsay France/University Photography [downloaded from http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/Feb13/earPrint.html]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/BioengineeredEar-300x200.jpg)