Antibiotics at the nanoscale = nanobiotics. For a more complete explanation, there’s this (Note: the video runs a little longer than most of the others embedded on this blog),

Before pushing further into this research, a note about antibiotic resistance. In a sense, we’ve created the problem we (those scientists in particular) are trying to solve.

Antibiotics and cleaning products kill 99.9% of the bacteria, leaving 0.1% that are immune. As so many living things on earth do, bacteria reproduce. Now, a new antibiotic is needed and discovered; it too kills 99.9% of the bacteria. The 0.1% left are immune to two antibiotics. And,so it goes.

As the scientists have made clear, we’re running out of options using standard methods and they’re hoping this ‘nanoparticle approach’ as described in a June 5, 2023 news item on Nanowerk will work, Note: A link has been removed,

Identifying whether and how a nanoparticle and protein will bind with one another is an important step toward being able to design antibiotics and antivirals on demand, and a computer model developed at the University of Michigan can do it.

The new tool could help find ways to stop antibiotic-resistant infections and new viruses—and aid in the design of nanoparticles for different purposes.

“Just in 2019, the number of people who died of antimicrobial resistance was 4.95 million. Even before COVID, which worsened the problem, studies showed that by 2050, the number of deaths by antibiotic resistance will be 10 million,” said Angela Violi, an Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of mechanical engineering, and corresponding author of the study that made the cover of Nature Computational Science (“Domain-agnostic predictions of nanoscale interactions in proteins and nanoparticles”).

In my ideal scenario, 20 or 30 years from now, I would like—given any superbug—to be able to quickly produce the best nanoparticles that can treat it.”

…

A June 5, 2023 University of Michigan news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more technical details, Note: A link has been removed,

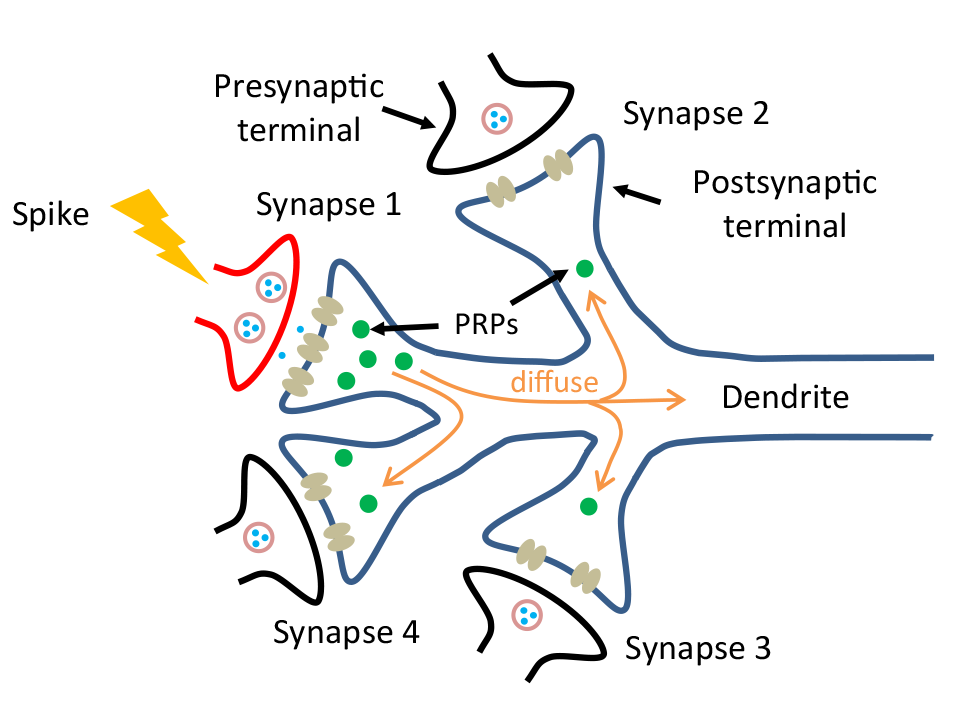

Much of the work within cells is done by proteins. Interaction sites on their surfaces can stitch molecules together, break them apart and perform other modifications—opening doorways into cells, breaking sugars down to release energy, building structures to support groups of cells and more. If we could design medicines that target crucial proteins in bacteria and viruses without harming our own cells, that would enable humans to fight new and changing diseases quickly.

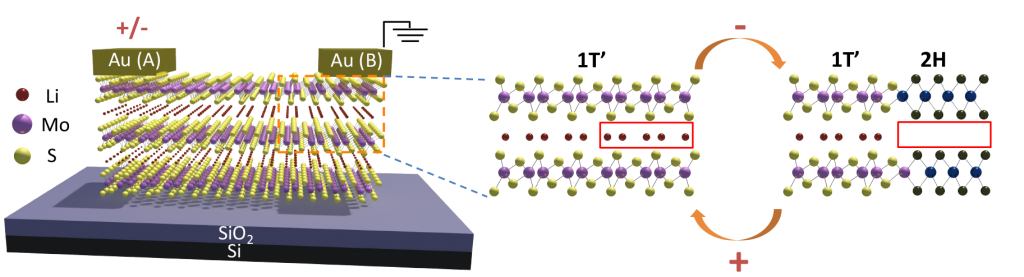

The new [computer] model, named NeCLAS [NeCLAS (Nanoparticle-Computed Ligand Affinity Scoring)], uses machine learning—the AI technique that powers the virtual assistant on your smartphone and ChatGPT. But instead of learning to process language, it absorbs structural models of proteins and their known interaction sites. From this information, it learns to extrapolate how proteins and nanoparticles might interact, predict binding sites and the likelihood of binding between them—as well as predicting interactions between two proteins or two nanoparticles.

“Other models exist, but ours is the best for predicting interactions between proteins and nanoparticles,” said Paolo Elvati, U-M associate research scientist in mechanical engineering.

AlphaFold, for example, is a widely used tool for predicting the 3D structure of a protein based on its building blocks, called amino acids. While this capacity is crucial, this is only the beginning: Discovering how these proteins assemble into larger structures and designing practical nanoscale systems are the next steps.

“That’s where NeCLAS comes in,” said Jacob Saldinger, U-M doctoral student in chemical engineering and first author of the study. “It goes beyond AlphaFold by showing how nanostructures will interact with one another, and it’s not limited to proteins. This enables researchers to understand the potential applications of nanoparticles and optimize their designs.”

The team tested three case studies for which they had additional data:

- Molecular tweezers, in which a molecule binds to a particular site on another molecule. This approach can stop harmful biological processes, such as the aggregation of protein plaques in diseases of the brain like Alzheimer’s.

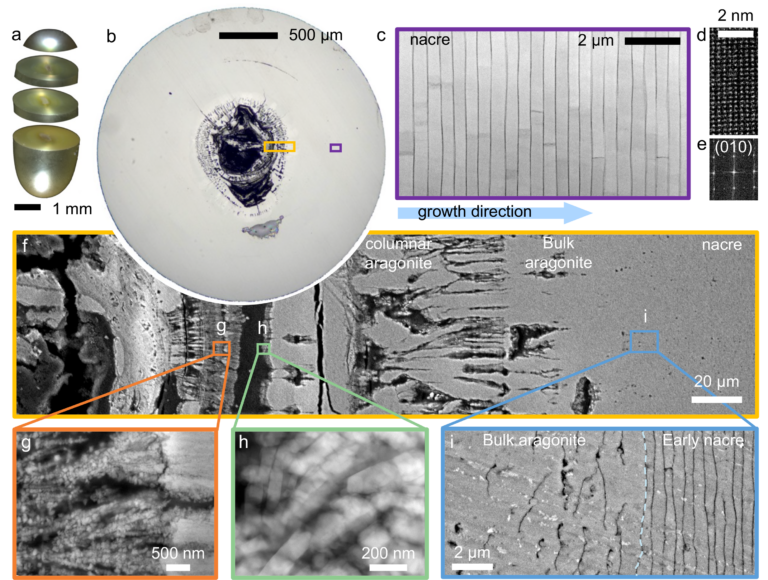

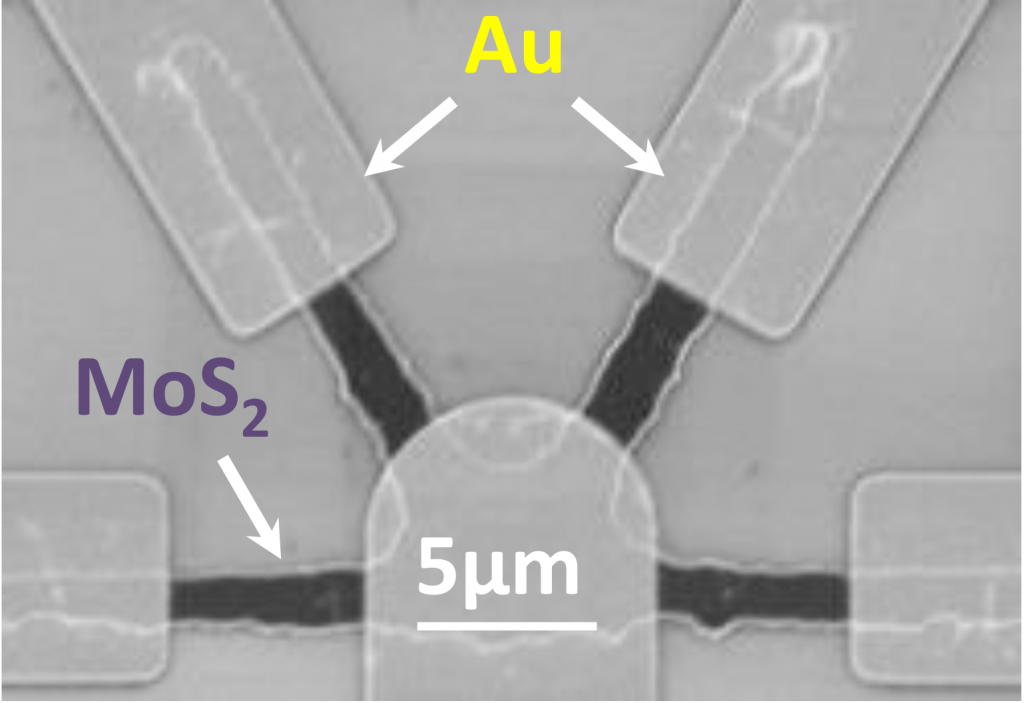

- How graphene quantum dots break up the biofilm produced by staph bacteria. These nanoparticles are flakes of carbon, no more than a few atomic layers thick and 0.0001 millimeters to a side. Breaking up biofilms is likely a crucial tool in fighting antibiotic-resistant infections—including the superbug methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), commonly acquired at hospitals.

- Whether graphene quantum dots would disperse in water, demonstrating the model’s ability to predict nanoparticle-nanoparticle binding even though it had been trained exclusively on protein-protein data.

While many protein-protein models set amino acids as the smallest unit that the model must consider, this doesn’t work for nanoparticles. Instead, the team set the size of that smallest feature to be roughly the size of the amino acid but then let the computer model decide where the boundaries between these minimum features were. The result is representations of proteins and nanoparticles that look a bit like collections of interconnected beads, providing more flexibility in exploring small scale interactions.

“Besides being more general, NeCLAS also uses way less training data than AlphaFold. We only have 21 nanoparticles to look at, so we have to use protein data in a clever way,” said Matt Raymond, U-M doctoral student in electrical and computer engineering and study co-author.

Next, the team intends to explore other biofilms and microorganisms, including viruses.

The Nature Computational Science study was funded by the University of Michigan Blue Sky Initiative, the Army Research Office and the National Science Foundation.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Domain-agnostic predictions of nanoscale interactions in proteins and nanoparticles by Jacob Charles Saldinger, Matt Raymond, Paolo Elvati & Angela Violi. Nature Computational Science volume 3, pages 393–402 (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-023-00438-x Published: 01 May 2023 Issue Date: May 2023

This paper is behind a paywall.