Michael Berger writes about a multisensory approach to neuromorphic computing inspired by butterflies in his February 2, 2024 Nanowerk Spotlight article, Note: Links have been removed,

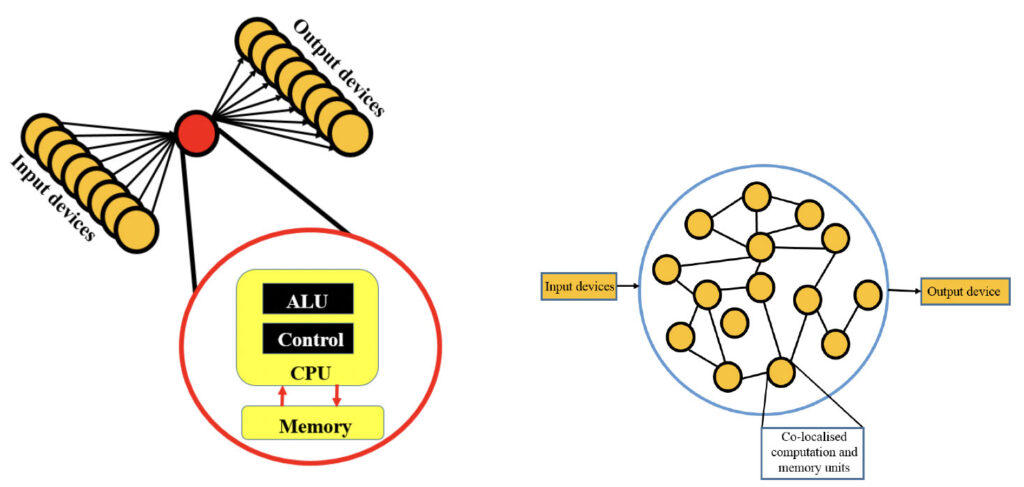

Artificial intelligence systems have historically struggled to integrate and interpret information from multiple senses the way animals intuitively do. Humans and other species rely on combining sight, sound, touch, taste and smell to better understand their surroundings and make decisions. However, the field of neuromorphic computing has largely focused on processing data from individual senses separately.

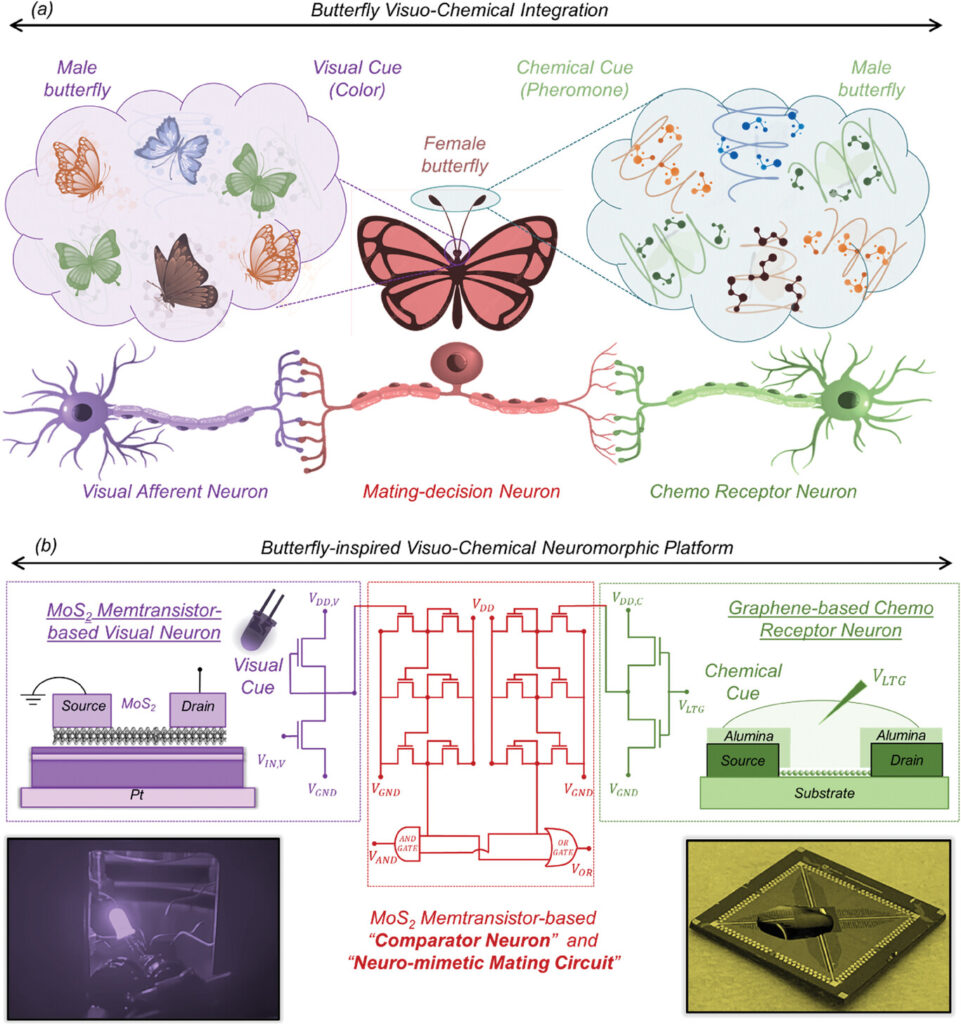

This unisensory approach stems in part from the lack of miniaturized hardware able to co-locate different sensing modules and enable in-sensor and near-sensor processing. Recent efforts have targeted fusing visual and tactile data. However, visuochemical integration, which merges visual and chemical information to emulate complex sensory processing such as that seen in nature—for instance, butterflies integrating visual signals with chemical cues for mating decisions—remains relatively unexplored. Smell can potentially alter visual perception, yet current AI leans heavily on visual inputs alone, missing a key aspect of biological cognition.

Now, researchers at Penn State University have developed bio-inspired hardware that embraces heterogeneous integration of nanomaterials to allow the co-location of chemical and visual sensors along with computing elements. This facilitates efficient visuochemical information processing and decision-making, taking cues from the courtship behaviors of a species of tropical butterfly.

In the paper published in Advanced Materials (“A Butterfly-Inspired Multisensory Neuromorphic Platform for Integration of Visual and Chemical Cues”), the researchers describe creating their visuochemical integration platform inspired by Heliconius butterflies. During mating, female butterflies rely on integrating visual signals like wing color from males along with chemical pheromones to select partners. Specialized neurons combine these visual and chemical cues to enable informed mate choice.

To emulate this capability, the team constructed hardware encompassing monolayer molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) memtransistors serving as visual capture and processing components. Meanwhile, graphene chemitransistors functioned as artificial olfactory receptors. Together, these nanomaterials provided the sensing, memory and computing elements necessary for visuochemical integration in a compact architecture.

…

While mating butterflies served as inspiration, the developed technology has much wider relevance. It represents a significant step toward overcoming the reliance of artificial intelligence on single data modalities. Enabling integration of multiple senses can greatly improve situational understanding and decision-making for autonomous robots, vehicles, monitoring devices and other systems interacting with complex environments.

The work also helps progress neuromorphic computing approaches seeking to emulate biological brains for next-generation ML acceleration, edge deployment and reduced power consumption. In nature, cross-modal learning underpins animals’ adaptable behavior and intelligence emerging from brains organizing sensory inputs into unified percepts. This research provides a blueprint for hardware co-locating sensors and processors to more closely replicate such capabilities

…

It’s fascinating to me how many times butterflies inspire science,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A Butterfly-Inspired Multisensory Neuromorphic Platform for Integration of Visual and Chemical Cues by Yikai Zheng, Subir Ghosh, Saptarshi Das. Advanced Materials SOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202307380 First published: 09 December 2023

This paper is open access.