From time to time I’ve featured ‘vampire technology’, a name I vastly prefer to energy harvesting or any of its variants. The focus has usually been on implantable electronic devices such as pacemakers and deep brain stimulators.

In this February 16, 2021 Nanowerk Spotlight article, Michael Berger broadens the focus to include other electronic devices,

Imagine edible medical devices that can be safely ingested by patients, perform a test or release a drug, and then transmit feedback to your smartphone; or an ingestible, Jell-O-like pill that monitors the stomach for up to a month.

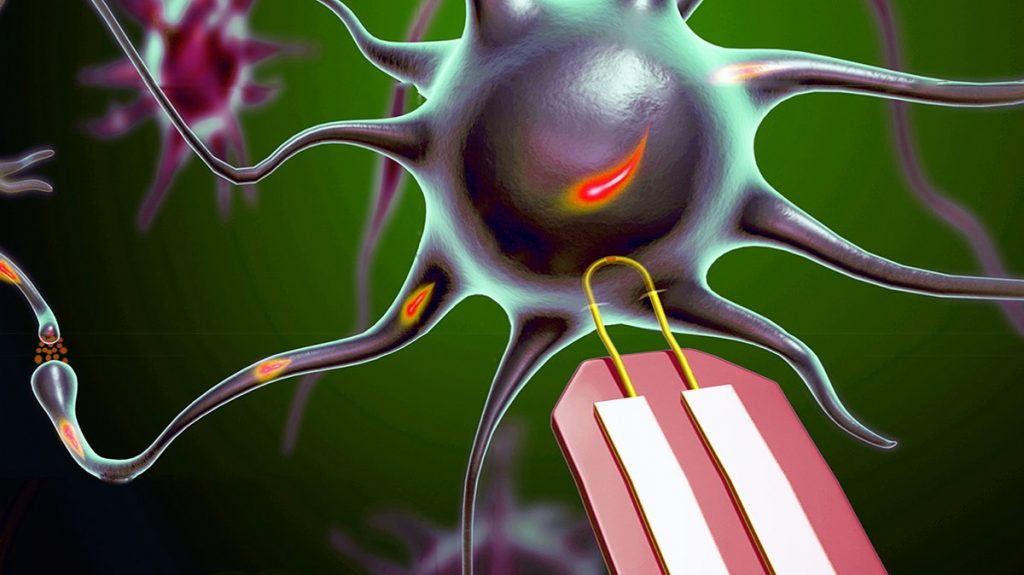

Devices like these, as well as a wide range of implantable biomedical electronic devices such as pacemakers, neurostimulators, subdermal blood sensors, capsule endoscopes, and drug pumps, can be useful tools for detecting physiological and pathophysiological signals, and providing treatments performed inside the body.

Advances in wireless communication enable medical devices to be untethered when in the human body. Advances in minimally invasive or semi-invasive surgical implantation procedures have enabled biomedical devices to be implanted in locations where clinically important biomarkers and physiological signals can be detected; it has also enabled direct administration of medication or treatment to a target location.

However, one major challenge in the development of these devices is the limited lifetime of their power sources. The energy requirements of biomedical electronic devices are highly dependent on their application and the complexity of the required electrical systems.

…

Berger’s commentary was occasioned by a review article in Advanced Functional Materials (link and citation to follow at the end of this post). Based on this review, the February 16, 2021 Nanowerk Spotlight article provides insight into the current state of affairs and challenges,

Biomedical electronic devices can be divided into three main categories depending on their application: diagnostic, therapeutic, and closed-loop systems. Each category has a different degree of complexity in the electronic system.

… most biomedical electronic devices are composed of a common set of components, including a power unit, sensors, actuators, a signal processing and control unit, and a data storage unit. Implantable and ingestible devices that require a great deal of data manipulation or large quantities of data logging also need to be wirelessly connected to an external device so that data can be transmitted to an external receiver and signal processing, data storage, and display can be performed more efficiently.

The power unit, which is composed of one or more energy sources – batteries, energy-harvesting, and energy transfer – as well as power management circuits, supplies electrical energy to the whole system.

…

Implantable medical devices such as cardiac pacemakers, neurostimulators and drug delivery devices are major medical tools to support life activity and provide new therapeutic strategies. Most such devices are powered by lithium batteries whose service life is as low as 10 years. Hence, many patients must undergo a major surgery to check the battery performance and replace the batteries as necessary.

In the last few decades, new battery technology has led to increases in the performance, reliability, and lifetime of batteries. However, challenges remain, especially in terms of volumetric energy density and safety.

Electronic miniaturization allows more functionalities to be added to devices, which increases power requirements. Recently, new material-based battery systems have been developed with higher energy densities.

…

Different locations and organ systems in the human body have access to different types of energy sources, such as mechanical, chemical, and electromagnetic energies.

…

Energy transfer technologies can deliver energy from outside the body to implanted or ingested devices. If devices are implanted at the locations where there are no accessible endogenous energies, exogenous energies in the form of ultrasonic or electromagnetic waves can penetrate through the biological barriers and wirelessly deliver the energies to the devices.

…

Both images embedded in the February 16, 2021 Nanowerk Spotlight article are informative. I’m particularly taken with the timeline which follows the development of batteries, energy harvesting/transfer devices, ingestible electronics, and implantable electronics. The first battery was in 1800 followed by ingestible and implantable electronics in the 1950s.

Berger’s commentary ends on this,

Concluding their review, the authors [in Advanced Functional Materials] note that low energy conversion efficiency and power output are the fundamental bottlenecks of energy harvesting and transfer devices. They suggest that additional studies are needed to improve the power output of energy harvesting and transfer devices so that they can be used to power various biomedical electronics.

Furthermore, durability studies of promising energy harvesters should be performed to evaluate their use in long-term applications. For degradable energy harvesting devices, such as friction-based energy harvesters and galvanic cells, improving the device lifetime is essential for use in real-life applications.

Finally, manufacturing cost is another factor to consider when commercializing novel batteries, energy harvesters, or energy transfer devices as power sources for medical devices.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Powering Implantable and Ingestible Electronics by So‐Yoon Yang, Vitor Sencadas, Siheng Sean You, Neil Zi‐Xun Jia, Shriya Sruthi Srinivasan, Hen‐Wei Huang, Abdelsalam Elrefaey Ahmed, Jia Ying Liang, Giovanni Traverso. Advanced Functional Materials DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202009289 First published: 04 February 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.

It may be possible to receive a full text PDF of the article from the authors. Try here.

There are others but here are two of my posts about ‘vampire energy’,

Harvesting the heart’s kinetic energy to power implants (July 26, 2019)

Vampire nanogenerators: 2017 (October 19, 2017)