COVID-19 vaccines require cold storage conditions (in some cases, extraordinarily cold storage), which pose problems with both storage and distribution.

A September 7, 2021 news item on phys.org describes research that may make vaccine distribution and storage problems a thing of the past (Note: A link has been removed),

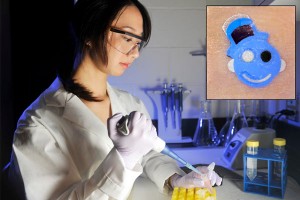

Nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego have developed COVID-19 vaccine candidates that can take the heat. Their key ingredients? Viruses from plants or bacteria.

The new fridge-free COVID-19 vaccines are still in the early stage of development. In mice, the vaccine candidates triggered high production of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. If they prove to be safe and effective in people, the vaccines could be a big game changer for global distribution efforts, including those in rural areas or resource-poor communities.

…

A September 7, 2021 University of California at San Diego (UCSD or UC San Diego) news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves further into the research,

“What’s exciting about our vaccine technology is that is thermally stable, so it could easily reach places where setting up ultra-low temperature freezers, or having trucks drive around with these freezers, is not going to be possible,” said Nicole Steinmetz, a professor of nanoengineering and the director of the Center for Nano-ImmunoEngineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

The vaccines are detailed in a paper published Sept. 7 [2021] in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

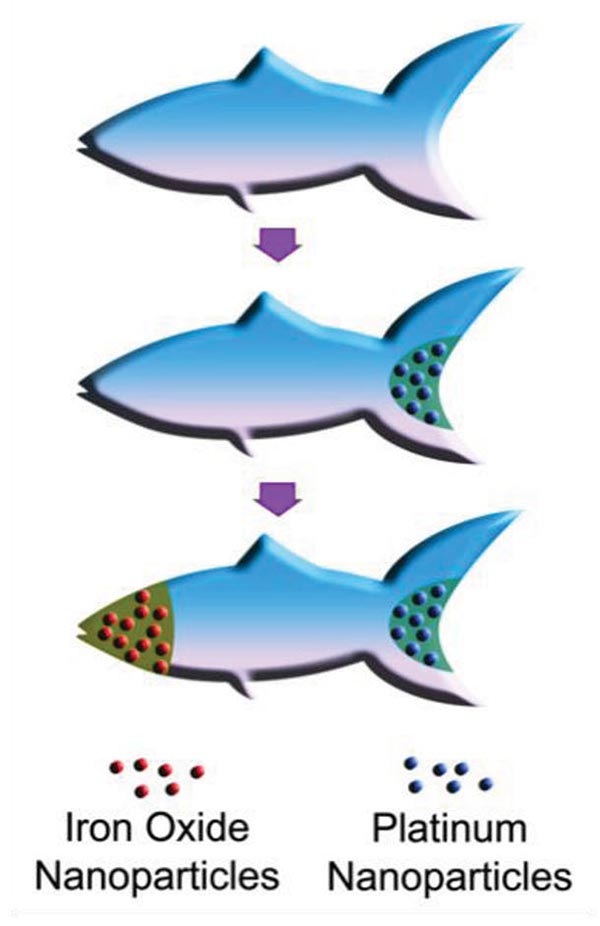

The researchers created two COVID-19 vaccine candidates. One is made from a plant virus, called cowpea mosaic virus. The other is made from a bacterial virus, or bacteriophage, called Q beta.

Both vaccines were made using similar recipes. The researchers used cowpea plants and E. coli bacteria to grow millions of copies of the plant virus and bacteriophage, respectively, in the form of ball-shaped nanoparticles. The researchers harvested these nanoparticles and then attached a small piece of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the surface. The finished products look like an infectious virus so the immune system can recognize them, but they are not infectious in animals and humans. The small piece of the spike protein attached to the surface is what stimulates the body to generate an immune response against the coronavirus.

The researchers note several advantages of using plant viruses and bacteriophages to make their vaccines. For one, they can be easy and inexpensive to produce at large scales. “Growing plants is relatively easy and involves infrastructure that’s not too sophisticated,” said Steinmetz. “And fermentation using bacteria is already an established process in the biopharmaceutical industry.”

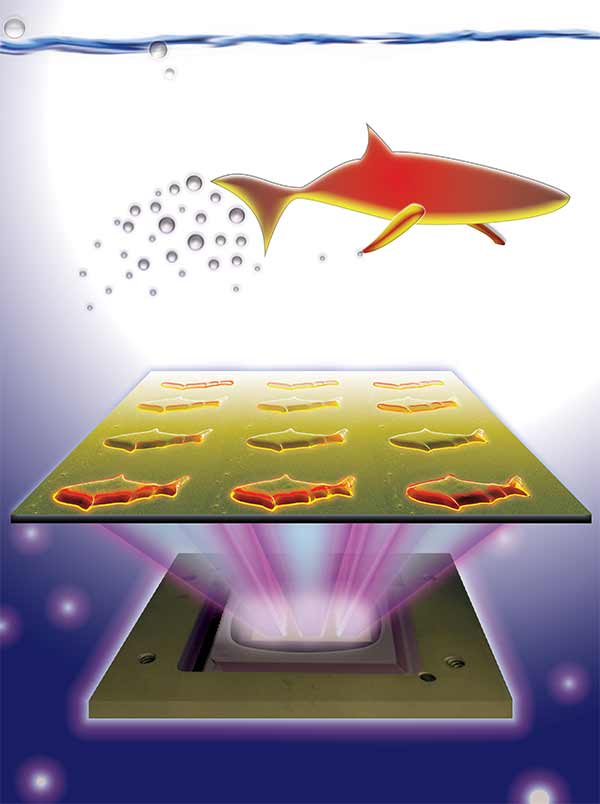

Another big advantage is that the plant virus and bacteriophage nanoparticles are extremely stable at high temperatures. As a result, the vaccines can be stored and shipped without needing to be kept cold. They also can be put through fabrication processes that use heat. The team is using such processes to package their vaccines into polymer implants and microneedle patches. These processes involve mixing the vaccine candidates with polymers and melting them together in an oven at temperatures close to 100 degrees Celsius. Being able to directly mix the plant virus and bacteriophage nanoparticles with the polymers from the start makes it easy and straightforward to create vaccine implants and patches.

The goal is to give people more options for getting a COVID-19 vaccine and making it more accessible. The implants, which are injected underneath the skin and slowly release vaccine over the course of a month, would only need to be administered once. And the microneedle patches, which can be worn on the arm without pain or discomfort, would allow people to self-administer the vaccine.

“Imagine if vaccine patches could be sent to the mailboxes of our most vulnerable people, rather than having them leave their homes and risk exposure,” said Jon Pokorski, a professor of nanoengineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering, whose team developed the technology to make the implants and microneedle patches.

“If clinics could offer a one-dose implant to those who would have a really hard time making it out for their second shot, that would offer protection for more of the population and we could have a better chance at stemming transmission,” added Pokorski, who is also a founding faculty member of the university’s Institute for Materials Discovery and Design.

In tests, the team’s COVID-19 vaccine candidates were administered to mice either via implants, microneedle patches, or as a series of two shots. All three methods produced high levels of neutralizing antibodies in the blood against SARS-CoV-2.

Potential Pan-Coronavirus Vaccine

These same antibodies also neutralized against the SARS virus, the researchers found.

It all comes down to the piece of the coronavirus spike protein that is attached to the surface of the nanoparticles. One of these pieces that Steinmetz’s team chose, called an epitope, is almost identical between SARS-CoV-2 and the original SARS virus.

“The fact that neutralization is so profound with an epitope that’s so well conserved among another deadly coronavirus is remarkable,” said co-author Matthew Shin, a nanoengineering Ph.D. student in Steinmetz’s lab. “This gives us hope for a potential pan-coronavirus vaccine that could offer protection against future pandemics.”

Another advantage of this particular epitope is that it is not affected by any of the SARS-CoV-2 mutations that have so far been reported. That’s because this epitope comes from a region of the spike protein that does not directly bind to cells. This is different from the epitopes in the currently administered COVID-19 vaccines, which come from the spike protein’s binding region. This is a region where a lot of the mutations have occurred. And some of these mutations have made the virus more contagious.

Epitopes from a nonbinding region are less likely to undergo these mutations, explained Oscar Ortega-Rivera, a postdoctoral researcher in Steinmetz’s lab and the study’s first author. “Based on our sequence analyses, the epitope that we chose is highly conserved amongst the SARS-CoV-2 variants.”

This means that the new COVID-19 vaccines could potentially be effective against the variants of concern, said Ortega-Rivera, and tests are currently underway to see what effect they have against the Delta variant, for example.

Plug and Play Vaccine

Another thing that gets Steinmetz really excited about this vaccine technology is the versatility it offers to make new vaccines. “Even if this technology does not make an impact for COVID-19, it can be quickly adapted for the next threat, the next virus X,” said Steinmetz.

Making these vaccines, she says, is “plug and play:” grow plant virus or bacteriophage nanoparticles from plants or bacteria, respectively, then attach a piece of the target virus, pathogen, or biomarker to the surface.

“We use the same nanoparticles, the same polymers, the same equipment, and the same chemistry to put everything together. The only variable really is the antigen that we stick to the surface,” said Steinmetz.

The resulting vaccines do not need to be kept cold. They can be packaged into implants or microneedle patches. Or, they can be directly administered in the traditional way via shots.

Steinmetz and Pokorski’s labs have used this recipe in previous studies to make vaccine candidates for diseases like HPV and cholesterol. And now they’ve shown that it works for making COVID-19 vaccine candidates as well.

Next Steps

The vaccines still have a long way to go before they make it into clinical trials. Moving forward, the team will test if the vaccines protect against infection from COVID-19, as well as its variants and other deadly coronaviruses, in vivo.

…

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Trivalent Subunit Vaccine Candidates for COVID-19 and Their Delivery Devices by Oscar A. Ortega-Rivera, Matthew D. Shin, Angela Chen, Veronique Beiss, Miguel A. Moreno-Gonzalez, Miguel A. Lopez-Ramirez, Maria Reynoso, Hong Wang, Brett L. Hurst, Joseph Wang, Jonathan K. Pokorski, and Nicole F. Steinmetz. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c06600 Publication Date:September 7, 2021 © 2021 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.