There was a Vancouver-born architect, Arthur Erickson, who adored concrete as a building material. In fact, he gained an international reputation for his ‘concrete’ work. I have never been a fan, especially after attending Simon Fraser University (one of Erickson’s early triumphs) in Vancouver (Canada) and experiencing the joy of deteriorating concrete structures.

This somewhat related news concerns cement, (from a Dec.7, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

Bringing order to disorder is key to making stronger and greener cement, the paste that binds concrete.

Scientists at Rice University have decoded the kinetic properties of cement and developed a way to “program” the microscopic, semicrystalline particles within. The process turns particles from disordered clumps into regimented cubes, spheres and other forms that combine to make the material less porous and more durable.

A Dec. 7, 2016 Rice University news release, which originated the news item, explains further (Note: Links have been removed),

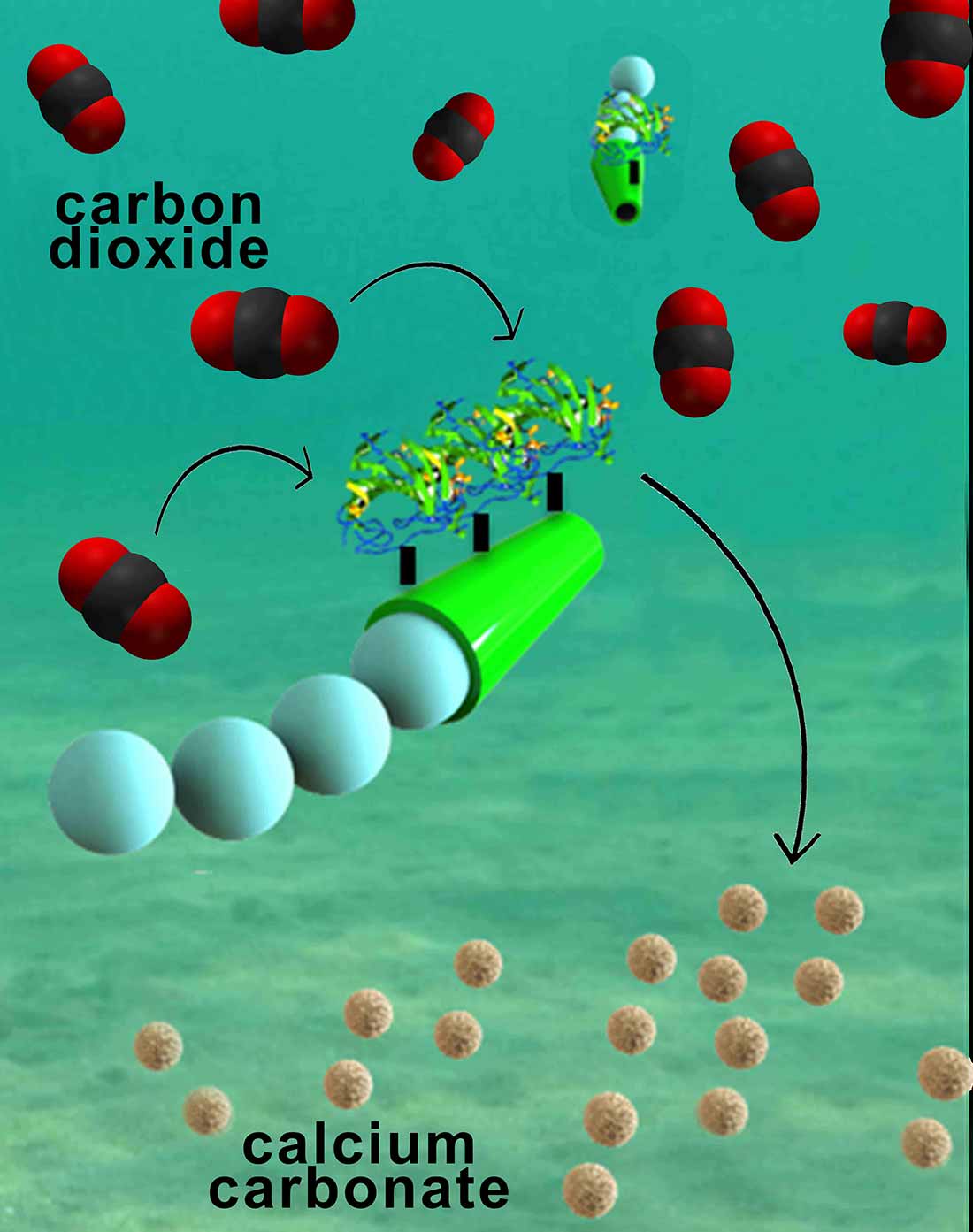

The technique may lead to stronger structures that require less concrete – and less is better, said Rice materials scientist and lead author Rouzbeh Shahsavari. Worldwide production of more than 3 billion tons of concrete a year now emits as much as 10 percent of the carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, released to the atmosphere.

Through extensive experiments, Shahsavari and his colleagues decoded the nanoscale reactions — or “morphogenesis” — of the crystallization within calcium-silicate hydrate (C-S-H) cement that holds concrete together.

For the first time, they synthesized C-S-H particles in a variety of shapes, including cubes, rectangular prisms, dendrites, core-shells and rhombohedra and mapped them into a unified morphology diagram for manufacturers and builders who wish to engineer concrete from the bottom up.

“We call it programmable cement,” he said. “The great advance of this work is that it’s the first step in controlling the kinetics of cement to get desired shapes. We show how one can control the morphology and size of the basic building blocks of C-S-H so that they can self-assemble into microstructures with far greater packing density compared with conventional amorphous C-S-H microstructures.”

He said the idea is akin to the self-assembly of metallic crystals and polymers. “It’s a hot area, and researchers are taking advantage of it,” Shahsavari said. “But when it comes to cement and concrete, it is extremely difficult to control their bottom-up assembly. Our work provides the first recipe for such advanced synthesis.

“The seed particles form first, automatically, in our reactions, and then they dominate the process as the rest of the material forms around them,” he said. “That’s the beauty of it. It’s in situ, seed-mediated growth and does not require external addition of seed particles, as commonly done in the industry to promote crystallization and growth.”

Previous techniques to create ordered crystals in C-S-H required high temperatures or pressures, prolonged reaction times and the use of organic precursors, but none were efficient or environmentally benign, Shahsavari said.

The Rice lab created well-shaped cubes and rectangles by adding small amounts of positive or negative ionic surfactants and calcium silicate to C-S-H and exposing the mix to carbon dioxide and ultrasonic sound. The crystal seeds took shape around surfactant micelles within 25 minutes. Decreasing the calcium silicate yielded more spherical particles and smaller cubes, while increasing it formed clumped spheres and interlocking cubes.

Once the calcite “seeds” form, they trigger the molecules around them to self-assemble into cubes, spheres and other shapes that are orders of magnitude larger. These can pack more tightly together in concrete than amorphous particles, Shahsavari said. Carefully modulating the precursor concentration, temperature and duration of the reaction varies the yield, size and morphology of the final particles.

The discovery is an important step in concrete research, he said. It builds upon his work as part of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology team that decoded cement’s molecular “DNA” in 2009. “There is currently no control over C-S-H shape,” Shahsavari said. “The concrete used today is an amorphous colloid with significant porosity that entails reduced strength and durability.”

Concrete is one focus of Shahsavari’s Rice lab, which has studied both its macroscale manufacture and intrinsic nanoscale properties. Because concrete is the world’s most common construction material and a significant source of atmospheric carbon dioxide, he is convinced of the importance of developing “greener” concrete.

The new technique has several environmental benefits, Shahsavari said. “One is that you need less of it (the concrete) because it is stronger. This stems from better packing of the cubic particles, which leads to stronger microstructures. The other is that it will be more durable. Less porosity makes it harder for unwanted chemicals to find a path through the concrete, so it does a better job of protecting steel reinforcement inside.”

The research required the team to develop a method to test microscopic concrete particles for strength. The researchers used a diamond-tipped nanoindenter to crush single cement particles with a flat edge.

They programmed the indenter to move from one nanoparticle to the next and crush it and gathered mechanical data on hundreds of particles of various shapes in one run. “Other research groups have tested bulk cement and concrete, but no group had ever probed the mechanics of single C-S-H particles and the effect of shape on mechanics of individual particles,” Shahsavari said.

He said strategies developed during the project could have implications for other applications, including bone tissue engineering, drug delivery and refractory materials, and could impact such other complex systems as ceramics and colloids.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Morphogenesis of Cement Hydrate by Sakineh E Moghaddam, vahid hejazi, Sung Hoon Hwang, Sreeprasad Srinavasan, Joseph B. Miller, Benhang Shi, Shuo Zhao, Irene Rusakova, Aali R. Alizadeh, Kenton Whitmire and Rouzbeh Shahsavari. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2016, DOI: 10.1039/C6TA09389B First published online 30 Nov 2016

I believe this paper is behind a paywall.