Here’s one of the more recent efforts to create fibres that are electronic and capable of being woven into a smart textile. (Details about a previous effort can be found at the end of this post.) Now for this one, from a Dec. 3, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily,

The quest to create affordable, durable and mass-produced ‘smart textiles’ has been given fresh impetus through the use of the wonder material Graphene.

An international team of scientists, led by Professor Monica Craciun from the University of Exeter Engineering department, has pioneered a new technique to create fully electronic fibres that can be incorporated into the production of everyday clothing.

A Dec. 3, 2018 University of Exeter press release (also on EurekAlert), provides more detail about the problems associated with wearable electronics and the solution being offered (Note: A link has been removed),

Currently, wearable electronics are achieved by essentially gluing devices to fabrics, which can mean they are too rigid and susceptible to malfunctioning.

The new research instead integrates the electronic devices into the fabric of the material, by coating electronic fibres with light-weight, durable components that will allow images to be shown directly on the fabric.

The research team believe that the discovery could revolutionise the creation of wearable electronic devices for use in a range of every day applications, as well as health monitoring, such as heart rates and blood pressure, and medical diagnostics.

The international collaborative research, which includes experts from the Centre for Graphene Science at the University of Exeter, the Universities of Aveiro and Lisbon in Portugal, and CenTexBel in Belgium, is published in the scientific journal Flexible Electronics.

Professor Craciun, co-author of the research said: “For truly wearable electronic devices to be achieved, it is vital that the components are able to be incorporated within the material, and not simply added to it.

Dr Elias Torres Alonso, Research Scientist at Graphenea and former PhD student in Professor Craciun’s team at Exeter added “This new research opens up the gateway for smart textiles to play a pivotal role in so many fields in the not-too-distant future. By weaving the graphene fibres into the fabric, we have created a new technique to all the full integration of electronics into textiles. The only limits from now are really within our own imagination.”

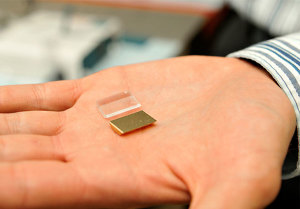

At just one atom thick, graphene is the thinnest substance capable of conducting electricity. It is very flexible and is one of the strongest known materials. The race has been on for scientists and engineers to adapt graphene for the use in wearable electronic devices in recent years.

This new research used existing polypropylene fibres – typically used in a host of commercial applications in the textile industry – to attach the new, graphene-based electronic fibres to create touch-sensor and light-emitting devices.

The new technique means that the fabrics can incorporate truly wearable displays without the need for electrodes, wires of additional materials.

Professor Saverio Russo, co-author and from the University of Exeter Physics department, added: “The incorporation of electronic devices on fabrics is something that scientists have tried to produce for a number of years, and is a truly game-changing advancement for modern technology.”

Dr Ana Neves, co-author and also from Exeter’s Engineering department added “The key to this new technique is that the textile fibres are flexible, comfortable and light, while being durable enough to cope with the demands of modern life.”

In 2015, an international team of scientists, including Professor Craciun, Professor Russo and Dr Ana Neves from the University of Exeter, have pioneered a new technique to embed transparent, flexible graphene electrodes into fibres commonly associated with the textile industry.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Graphene electronic fibres with touch-sensing and light-emitting functionalities for smart textiles by Elias Torres Alonso, Daniela P. Rodrigues, Mukond Khetani, Dong-Wook Shin, Adolfo De Sanctis, Hugo Joulie, Isabel de Schrijver, Anna Baldycheva, Helena Alves, Ana I. S. Neves, Saverio Russo & Monica F. Craciun. Flexible Electronicsvolume 2, Article number: 25 (2018) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-018-0040-2 Published 25 September 2018

This paper is open access.

I have an earlier post about an effort to weave electronics into textiles for soldiers, from an April 5, 2012 posting,

I gather that today’s soldier (aka, warfighter) is carrying as many batteries as weapons. Apparently, the average soldier carries a couple of kilos worth of batteries and cables to keep their various pieces of equipment operational. The UK’s Centre for Defence Enterprise (part of the Ministry of Defence) has announced that this situation is about to change as a consequence of a recently funded research project with a company called Intelligent Textiles. From Bob Yirka’s April 3, 2012 news item for physorg.com,

To get rid of the cables, a company called Intelligent Textiles has come up with a type of yarn that can conduct electricity, which can be woven directly into the fabric of the uniform. And because they allow the uniform itself to become one large conductive unit, the need for multiple batteries can be eliminated as well.

…

I dug down to find more information about this UK initiative and the Intelligent Textiles company but the trail seems to end in 2015. Still, I did find a Canadian connection (for those who don’t know I’m a Canuck) and more about Intelligent Textile’s work with the British military in this Sept. 21, 2015 article by Barry Collins for alphr.com (Note: Links have been removed),

A two-person firm operating from a small workshop in Staines-upon-Thames, Intelligent Textiles has recently landed a multimillion-pound deal with the US Department of Defense, and is working with the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to bring its potentially life-saving technology to British soldiers. Not bad for a company that only a few years ago was selling novelty cushions.

Intelligent Textiles was born in 2002, almost by accident. Asha Peta Thompson, an arts student at Central Saint Martins, had been using textiles to teach children with special needs. That work led to a research grant from Brunel University, where she was part of a team tasked with creating a “talking jacket” for the disabled. The garment was designed to help cerebral palsy sufferers to communicate, by pressing a button on the jacket to say “my name is Peter”, for example, instead of having a Stephen Hawking-like communicator in front of them.

Another member of that Brunel team was engineering lecturer Dr Stan Swallow, who was providing the electronics expertise for the project. Pretty soon, the pair realised the prototype waistcoat they were working on wasn’t going to work: it was cumbersome, stuffed with wires, and difficult to manufacture. “That’s when we had the idea that we could weave tiny mechanical switches into the surface of the fabric,” said Thompson.

…

The conductive weave had several advantages over packing electronics into garments. “It reduces the amount of cables,” said Thompson. “It can be worn and it’s also washable, so it’s more durable. It doesn’t break; it can be worn next to the skin; it’s soft. It has all the qualities of a piece of fabric, so it’s a way of repackaging the electronics in a way that’s more user-friendly and more comfortable.” The key to Intelligent Textiles’ product isn’t so much the nature of the raw materials used, but the way they’re woven together. “All our patents are in how we weave the fabric,” Thompson explained. “We weave two conductive yarns to make a tiny mechanical switch that is perfectly separated or perfectly connected. We can weave an electronic circuit board into the fabric itself.”

…

Intelligent Textiles’ big break into the military market came when they met a British textiles firm that was supplying camouflage gear to the Canadian armed forces. [emphasis mine] The firm was attending an exhibition in Canada and invited the Intelligent Textiles duo to join them. “We showed a heated glove and an iPod controller,” said Thompson. “The Canadians said ‘that’s really fantastic, but all we need is power. Do you think you could weave a piece of fabric that distributes power?’ We said, ‘we’re already doing it’.”Before long it wasn’t only power that the Canadians wanted transmitted through the fabric, but data.

“The problem a soldier faces at the moment is that he’s carrying 60 AA batteries [to power all the equipment he carries],” said Thompson. “He doesn’t know what state of charge those batteries are at, and they’re incredibly heavy. He also has wires and cables running around the system. He has snag hazards – when he’s going into a firefight, he can get caught on door handles and branches, so cables are a real no-no.”

The Canadians invited the pair to speak at a NATO conference, where they were approached by military brass with more familiar accents. “It was there that we were spotted by the British MoD, who said ‘wow, this is a British technology but you’re being funded by Canada’,” said Thompson. That led to £235,000 of funding from the Centre for Defence Enterprise (CDE) – the money they needed to develop a fabric wiring system that runs all the way through the soldier’s vest, helmet and backpack.

…

There are more details about the 2015 state of affairs, textiles-wise, in a March 11, 2015 article by Richard Trenholm for CNET.com (Note: A link has been removed),

Speaking at the Wearable Technology Show here, Swallow describes IT [Intelligent Textiles]L as a textile company that “pretends to be a military company…it’s funny how you slip into these domains.”

One domain where this high-tech fabric has seen frontline action is in the Canadian military’s IAV Stryker armoured personnel carrier. ITL developed a full QWERTY keyboard in a single piece of fabric for use in the Stryker, replacing a traditional hardware keyboard that involved 100 components. Multiple components allow for repair, but ITL knits in redundancy so the fabric can “degrade gracefully”. The keyboard works the same as the traditional hardware, with the bonus that it’s less likely to fall on a soldier’s head, and with just one glaring downside: troops can no longer use it as a step for getting in and out of the vehicle.

…

An armoured car with knitted controls is one thing, but where the technology comes into its own is when used about the person. ITL has worked on vests like the JTAC, a system “for the guys who call down airstrikes” and need “extra computing oomph.” Then there’s SWIPES, a part of the US military’s Nett Warrior system — which uses a chest-mounted Samsung Galaxy Note 2 smartphone — and British military company BAE’s Broadsword system.

ITL is currently working on Spirit, a “truly wearable system” for the US Army and United States Marine Corps. It’s designed to be modular, scalable, intuitive and invisible.

…

While this isn’t an ITL product, this video about Broadsword technology from BAE does give you some idea of what wearable technology for soldiers is like,

If anyone should have the latest news about Intelligent Textile’s efforts, please do share in the comments section.

I do have one other posting about textiles and the military, which is dated May 9, 2012, but while it does reference US efforts it is not directly related to weaving electronics into solder’s (warfighter’s) gear.

You can find CenTexBel (Belgian Textile Rsearch Centre) here and Graphenea here. Both are mentioned in the University of Exeter press release.