I have always imagined the love of maple syrup to be a universal love. A friend who moved to Canada from somewhere else in the world disillusioned me on that subject. She claims to be unable to grasp why anyone would love maple syrup. Should you recognize yourself in those words you may not find this post all that interesting.

However, maple syrup lovers may find this May 5, 2020 news item on Nanowerk a bit disconcerting,

It’s said that maple syrup is Quebec’s liquid gold. Now scientists at Université de Montréal have found a way to use real gold — in the form of nanoparticles — to quickly find out how the syrup tastes.

The new method — a kind of artificial tongue — is validated in a study published in Analytical Methods (“High-throughput plasmonic tongue using an aggregation assay and nonspecific interactions: classification of taste profiles in maple syrup”), the journal of the Royal Society of Chemistry, in the United Kingdom.

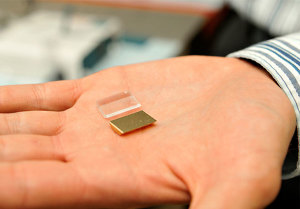

The “tongue” is a colorimetric test that detects changes in colour to show how a sample of maple syrup tastes. The result is visible to the naked eye in a matter of seconds and is useful to producers.

“The artificial tongue is simpler than a human tongue: it can’t distinguish the complex flavour profiles that we can detect,” said UdeM chemistry professor Jean-François Masson, who led the study. “Our device works specifically to detect flavour differences in maple syrup as it’s being produced.”

…

There is more information but the central question as to why anyone would want an artificial tongue for tasting maple syrup is never answered (presumably they want to speed up production and ensure more consistent classification) nor is there much in the way of technical detail in a May 5, 2019 Université de Montréal news release (also on EurekAlert),

1,818 samples tested

The artificial tongue was validated by analyzing 1,818 samples of maple syrup from different regions of Quebec. The syrups that were analyzed represented the various known aromatic profiles and colours of syrup, from golden to dark brown.

“We designed the ‘tongue’ at the request of the Québec Maple Syrup Producers to detect the presence of different flavour profiles,” explained Simon Forest, the study’s first author. “The tool takes into account the product’s olfactory and taste properties.”

Maple syrup has a molecular complexity similar to that of wine. Its taste is delicate, without bitterness, and it has a subtle aroma. During the production process, specialized human tasters are employed to judge which profile each batch fits into.

“The development of the artificial tongue is intended to support the colossal work that is being done in the field to do the first sorting of syrups quickly and classify them according to their qualities,” said Masson.

Red for the best, blue for the rest

The researchers compare the artificial tongue to a pH test for a swimming pool. You simply pour a few drops of syrup into the gold nanoparticle reagent and wait about 10 seconds.

If the result stays in the red spectrum, it has the characteristics of a premium quality syrup, the kind best loved by consumers and sold in grocery stores or exported.

If, on the other hand, the test turns blue, the syrup may have a flavour “defect”, which may be treated as an industrial syrup for use in processing.

“It doesn’t mean the syrup is not good for consumption or that it has a different sugar level,” Masson said of the “blue” type syrup, which the food industry uses as a natural sweetener in other products. “It just may not have the usual desired characteristics, and so can’t be sold directly in bottles to consumers.”

60 categories of taste

Caramelized, woody, green, smoked, salty, burnt — the taste of maple syrup has as many as 60 categories to fit into. Maple syrup is essentially a concentrated sugar solution of 66 per cent sucrose and 33 per cent water; the remaining one per cent of other compounds determines the taste.

Like wine, the taste of maple syrup changes according to a variety of factors, including the harvest period, the region, production and storage methods and, of course, the weather. Too much variation in temperature over a weekend, for instance, can greatly affect the taste profile of the product.

The artificial tongue developed at UdeM could someday be adapted for tasting wine or fruit juice, Masson said, as well as be useful in a number of other agrifood contexts.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A high-throughput plasmonic tongue using an aggregation assay and nonspecific interactions: classification of taste profiles in maple syrup by Simon Forest, Trevor Théorêt, Julien Coutu, and Jean-Francois Masson. Anal. Methods, 2020, Advance Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/C9AY01942A First published 05 May 2020

This paper is behind a paywall.