This brainlike transistor (not a memristor) is important because it functions at room temperature as opposed to others, which require cryogenic temperatures.

A December 20, 2023 Northwestern University news release (received via email; also on EurekAlert) fills in the details,

- Researchers develop transistor that simultaneously processes and stores information like the human brain

- Transistor goes beyond categorization tasks to perform associative learning

- Transistor identified similar patterns, even when given imperfect input

- Previous similar devices could only operate at cryogenic temperatures; new transistor operates at room temperature, making it more practical

EVANSTON, Ill. — Taking inspiration from the human brain, researchers have developed a new synaptic transistor capable of higher-level thinking.

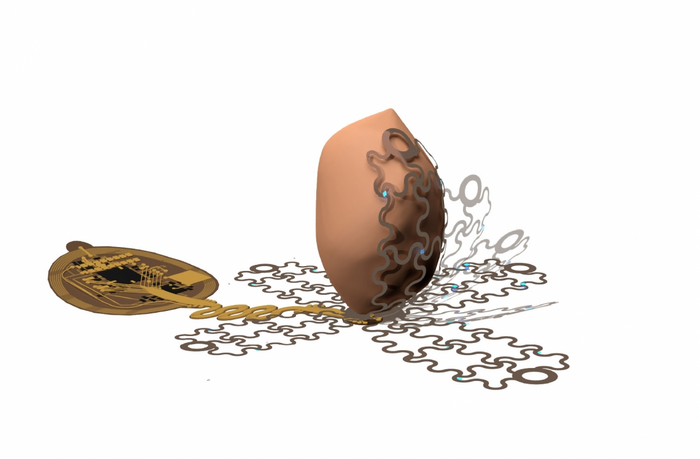

Designed by researchers at Northwestern University, Boston College and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the device simultaneously processes and stores information just like the human brain. In new experiments, the researchers demonstrated that the transistor goes beyond simple machine-learning tasks to categorize data and is capable of performing associative learning.

Although previous studies have leveraged similar strategies to develop brain-like computing devices, those transistors cannot function outside cryogenic temperatures. The new device, by contrast, is stable at room temperatures. It also operates at fast speeds, consumes very little energy and retains stored information even when power is removed, making it ideal for real-world applications.

The study was published today (Dec. 20 [2023]) in the journal Nature.

“The brain has a fundamentally different architecture than a digital computer,” said Northwestern’s Mark C. Hersam, who co-led the research. “In a digital computer, data move back and forth between a microprocessor and memory, which consumes a lot of energy and creates a bottleneck when attempting to perform multiple tasks at the same time. On the other hand, in the brain, memory and information processing are co-located and fully integrated, resulting in orders of magnitude higher energy efficiency. Our synaptic transistor similarly achieves concurrent memory and information processing functionality to more faithfully mimic the brain.”

Hersam is the Walter P. Murphy Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering. He also is chair of the department of materials science and engineering, director of the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center and member of the International Institute for Nanotechnology. Hersam co-led the research with Qiong Ma of Boston College and Pablo Jarillo-Herrero of MIT.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have motivated researchers to develop computers that operate more like the human brain. Conventional, digital computing systems have separate processing and storage units, causing data-intensive tasks to devour large amounts of energy. With smart devices continuously collecting vast quantities of data, researchers are scrambling to uncover new ways to process it all without consuming an increasing amount of power. Currently, the memory resistor, or “memristor,” is the most well-developed technology that can perform combined processing and memory function. But memristors still suffer from energy costly switching.

“For several decades, the paradigm in electronics has been to build everything out of transistors and use the same silicon architecture,” Hersam said. “Significant progress has been made by simply packing more and more transistors into integrated circuits. You cannot deny the success of that strategy, but it comes at the cost of high power consumption, especially in the current era of big data where digital computing is on track to overwhelm the grid. We have to rethink computing hardware, especially for AI and machine-learning tasks.”

To rethink this paradigm, Hersam and his team explored new advances in the physics of moiré patterns, a type of geometrical design that arises when two patterns are layered on top of one another. When two-dimensional materials are stacked, new properties emerge that do not exist in one layer alone. And when those layers are twisted to form a moiré pattern, unprecedented tunability of electronic properties becomes possible.

For the new device, the researchers combined two different types of atomically thin materials: bilayer graphene and hexagonal boron nitride. When stacked and purposefully twisted, the materials formed a moiré pattern. By rotating one layer relative to the other, the researchers could achieve different electronic properties in each graphene layer even though they are separated by only atomic-scale dimensions. With the right choice of twist, researchers harnessed moiré physics for neuromorphic functionality at room temperature.

“With twist as a new design parameter, the number of permutations is vast,” Hersam said. “Graphene and hexagonal boron nitride are very similar structurally but just different enough that you get exceptionally strong moiré effects.”

To test the transistor, Hersam and his team trained it to recognize similar — but not identical — patterns. Just earlier this month, Hersam introduced a new nanoelectronic device capable of analyzing and categorizing data in an energy-efficient manner, but his new synaptic transistor takes machine learning and AI one leap further.

“If AI is meant to mimic human thought, one of the lowest-level tasks would be to classify data, which is simply sorting into bins,” Hersam said. “Our goal is to advance AI technology in the direction of higher-level thinking. Real-world conditions are often more complicated than current AI algorithms can handle, so we tested our new devices under more complicated conditions to verify their advanced capabilities.”

First the researchers showed the device one pattern: 000 (three zeros in a row). Then, they asked the AI to identify similar patterns, such as 111 or 101. “If we trained it to detect 000 and then gave it 111 and 101, it knows 111 is more similar to 000 than 101,” Hersam explained. “000 and 111 are not exactly the same, but both are three digits in a row. Recognizing that similarity is a higher-level form of cognition known as associative learning.”

In experiments, the new synaptic transistor successfully recognized similar patterns, displaying its associative memory. Even when the researchers threw curveballs — like giving it incomplete patterns — it still successfully demonstrated associative learning.

“Current AI can be easy to confuse, which can cause major problems in certain contexts,” Hersam said. “Imagine if you are using a self-driving vehicle, and the weather conditions deteriorate. The vehicle might not be able to interpret the more complicated sensor data as well as a human driver could. But even when we gave our transistor imperfect input, it could still identify the correct response.”

The study, “Moiré synaptic transistor with room-temperature neuromorphic functionality,” was primarily supported by the National Science Foundation.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Moiré synaptic transistor with room-temperature neuromorphic functionality by Xiaodong Yan, Zhiren Zheng, Vinod K. Sangwan, Justin H. Qian, Xueqiao Wang, Stephanie E. Liu, Kenji Watanabe, Takashi Taniguchi, Su-Yang Xu, Pablo Jarillo-Herrero, Qiong Ma & Mark C. Hersam. Nature volume 624, pages 551–556 (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06791-1 Published online: 20 December 2023 Issue Date: 21 December 2023

This paper is behind a paywall.