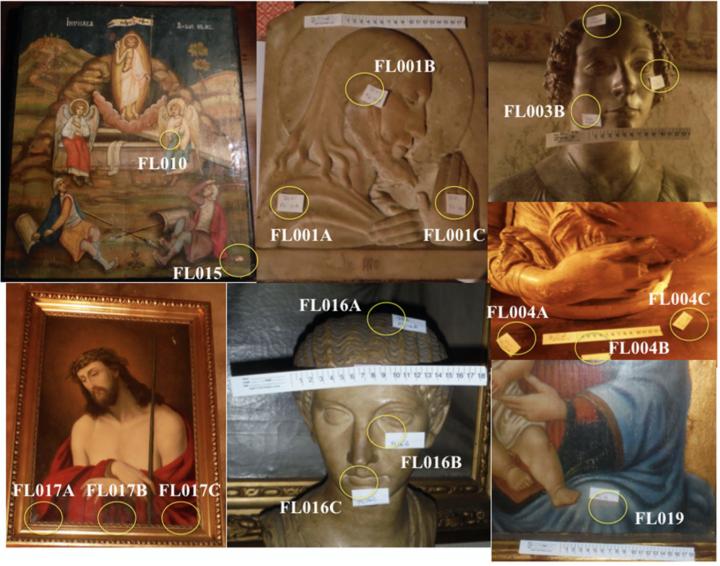

First, there was the story about art masterpieces turning into soap (my June 22, 2017 posting) and now, it seems that microbes may also constitute a problem. Before getting to the latest research, here’s are some images the researchers are using to illustrate their work,

I’m not sure what that has to do with anything but I do love dragonflies. This next image seems more relevant to the research,

It turns out, the researchers are releasing two pieces of research in the same press release, neither having much to do with the other. They (art conservation rresearch, first and, then, research into vision [hence the dragonfly] and da Vinci’s eyes) are both described in a June 18, 2020 J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI)-Leonardo Da Vinci DNA Project press release (also on EurekAlert),

A new study of the microbial settlers on old paintings, sculptures, and other forms of art charts a potential path for preserving, restoring, and confirming the geographic origin of some of humanity’s greatest treasures.

Genetics scientists with the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI), collaborating with the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project and supported by the Richard Lounsbery Foundation, say identifying and managing communities of microbes on art may offer museums and collectors a new way to stem the deterioration of priceless possessions, and to unmask counterfeits in the $60 billion a year art market.

Manolito G. Torralba, Claire Kuelbs, Kelvin Jens Moncera, and Karen E. Nelson of the JCVI, La Jolla, California, and Rhonda Roby of the Alameda California County Sheriff’s Office Crime Laboratory, used small, dry polyester swabs to gently collect microbes from centuries-old, Renaissance-style art in a private collector’s home in Florence, Italy. Their findings are published in the journal Microbial Ecology .

The genetic detectives caution that additional time and research are needed to formally convict microbes as a culprit in artwork decay but consider their most interesting find to be “oxidase positive” microbes primarily on painted wood and canvas surfaces.

These species can dine on organic and inorganic compounds often found in paints, in glue, and in the cellulose in paper, canvas, and wood. Using oxygen for energy production, they can produce water or hydrogen peroxide, a chemical used in disinfectants and bleaches.

“Such byproducts are likely to influence the presence of mold and the overall rate of deterioration,” the paper says.

“Though prior studies have attempted to characterize the microbial composition associated with artwork decay, our results summarize the first large scale genomics-based study to understand the microbial communities associated with aging artwork.”

The study builds on an earlier one in which the authors compared hairs collected from people in the Washington D.C., and San Diego, CA. areas, finding that microbial signatures and patterns are geographically distinguishable.

In the art world context, studying microbes clinging to the surface of a work of art may help confirm its geographic origin and authenticity or identify counterfeits.

Lead author Manolito G. Torralba notes that, as art’s value continues to climb, preservation is increasingly important to museums and collectors alike, and typically involves mostly the monitoring and adjusting of lighting, heat, and moisture.

Adding genomics science to these efforts offers advantages of “immense potential.”

The study says microbial populations “were easily discernible between the different types of substrates sampled,” with those on stone and marble art more diverse than wood and canvas. This is “likely due to the porous nature of stone and marble harboring additional organisms and potentially moisture and nutrients, along with the likelihood of biofilm formation.”

As well, microbial diversity on paintings is likely lower because few organisms can metabolize the meagre nutrients offered by oil-based paint.

“Though our sample size is low, the novelty of our study has provided the art and scientific communities with evidence that microbial signatures are capable of differentiating artwork according to their substrate,” the paper says.

“Future studies would benefit from working with samples whose authorship, ownership, and care are well-documented, although documentation about care of works of art (e.g., whether and how they were cleaned) seems rare before the mid-twentieth century.”

“Of particular interest would be the presence and activity of oil-degrading enzymes. Such approaches will lead to fully understanding which organism(s) are responsible for the rapid decay of artwork while potentially using this information to target these organisms to prevent degradation.”

“Focusing on reducing the abundance of such destructive organisms has great potential in preserving and restoring important pieces of human history.”

Biology in Art

The paper was supported by the US-based Richard Lounsbery Foundation as part of its “biology in art” research theme, which has also included seed funding efforts to obtain and sequence the genome of Leonardo da Vinci.

The Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project involves scientists in France (where Leonardo lived during his final years and was buried), Italy (where his father and other relatives were buried, and descendants of his half-brothers still live), Spain (whose National Library holds 700 pages of his notebooks), and the US (where forensic DNA skills flourish).

The Leonardo project has convened molecular biologists, population geneticists, microbiologists, forensic experts, and physicians working together with other natural scientists and with genealogists, historians, artists, and curators to discover and decode previously inaccessible knowledge and to preserve cultural heritage.

Related news release: Leonardo da Vinci’s DNA: Experts unite to shine modern light on a Renaissance master http://bit.ly/2FG4jJu

Measuring Leonardo da Vinci’s “quick eye” 500 years later.

Could he have played major-league baseball?

Famous art historians and biographers such as Sir Kenneth Clark and Walter Isaacson have written about Leonardo da Vinci’s “quick eye” because of the way he accurately captured fleeting expressions, wings during bird flight, and patterns in swirling water. But until now no one had tried to put a number on this aspect of Leonardo’s extraordinary visual acuity.

David S. Thaler of the University of Basel, and a guest investigator in the Program for the Human Environment at The Rockefeller University, does, allowing comparison of Leonardo with modern measures. Leonardo fares quite well.

Thaler’s estimate hinges on Leonardo’s observation that the fore and hind wings of a dragonfly are out of phase — not verified until centuries later by slow motion photography (see e.g. https://youtu.be/Lw2dfjYENNE?t=44).

To quote Isaacson’s translation of Leonardo’s notebook: “The dragonfly flies with four wings, and when those in front are raised those behind are lowered.”

Thaler challenged himself and friends to try seeing if that’s true, but they all saw only blurs.

High-speed camera studies by others show the fore and hind wingbeats of dragonflies vary by 20 to 10 milliseconds — one fiftieth to one hundredth of a second — beyond average human perception.

Thaler notes that “flicker fusion frequency” (FFF) — akin to a motion picture’s frames per second — is used to quantify and measure “temporal acuity” in human vision.

When frames per second exceed the number of frames the viewer can perceive individually, the brain constructs the illusion of continuous movement. The average person’s FFF is between 20 to 40 frames per second; current motion pictures present 48 or 72 frames per second.

To accurately see the angle between dragonfly wings would require temporal acuity in the range of 50 to 100 frames per second.

Thaler believes genetics will account for variations in FFF among different species, which range from a low of 12 in some nocturnal insects to over 300 in Fire Beetles. We simply do not know what accounts for human variation. Training and genetics may both play important roles.

“Perhaps the clearest contemporary case for a fast flicker fusion frequency in humans is in American baseball, because it is said that elite batters can see the seams on a pitched baseball,” even when rotating 30 to 50 times per second with two or four seams facing the batter. A batter would need Leonardo-esque FFF to spot the seams on most inbound baseballs.

Thaler suggests further study to compare the genome of individuals and species with unusually high FFF, including, if possible, Leonardo’s DNA.

Flicker fusion for focus, attention, and affection

In a companion paper, Thaler describes how Leonardo used psychophysics that would only be understood centuries later — and about which a lot remains to be learned today — to communicate deep beauty and emotion.

Leonardo was master of a technique known as sfumato (the word derived from the Italian sfumare, “to tone down” or “to evaporate like smoke”), which describes a subtle blur of edges and blending of colors without sharp focus or distinct lines.

Leonardo expert Martin Kemp has noted that Leonardo’s sfumato sometimes involves a distance dependence which is akin to the focal plane of a camera. Yet, at other times, features at the same distance have selective sfumato so simple plane of focus is not the whole answer.

Thaler suggests that Leonardo achieved selective soft focus in portraits by painting in overcast or evening light, where the eyes’ pupils enlarge to let in more light but have a narrow plane of sharp focus.

To quote Leonardo’s notebook, under the heading “Selecting the light which gives most grace to faces”: “In the evening and when the weather is dull, what softness and delicacy you may perceive in the faces of men and women.” In dim light pupils enlarge to let in more light but their depth of field decreases.

By measuring the size of the portrait’s pupils, Thaler inferred Leonardo’s depth of focus. He says Leonardo likely sensed this effect, perhaps unconsciously in the realm of his artistic sensibility. The pupil / aperture effect on depth of focus wasn’t explained until the mid-1800s, centuries after Leonardo’s birth in Vinci, Italy in 1452.

What about selective focus at equal distance? In this case Leonardo may have taken advantage of the fovea, the small area on the back of the eye where detail is sharpest.

Most of us move our eyes around and because of our slower flicker fusion frequency we construct a single 3D image of the world by jamming together many partially in-focus images. Leonardo realized and “froze” separate snapshots with which we construct ordinary perception.

Says Thaler: “We study Leonardo not only to learn about him but to learn about ourselves and further human potential.”

Thaler’s papers (at https://bit.ly/2WZ2cwo and https://bit.ly/2ZBj7Hi) evolved from talks at meetings of the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project in Italy (2018), Spain and France (2019).

They form part of a collection of papers presented at a recent colloquium in Amboise, France, now being readied for publication in a book: Actes du Colloque International d’Amboise: Leonardo de Vinci, Anatomiste. Pionnier de l’Anatomie comparée, de la Biomécanique, de la Bionique et de la Physiognomonie. Edited by Henry de Lumley, President, Institute of Human Paleontology, Paris, and originally planned for release in late spring, 2020, publication was delayed by the global virus pandemic but should be available at CNRS Editions in the second half of the summer.

Other papers in the collection cover a range of topics, including how Leonardo used his knowledge of anatomy, gained by performing autopsies on dozens of cadavers, to achieve Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile.

Leonardo also used it to exact revenge on academics and scientists who ridiculed him for lacking a classical education, sketching them with absurdly deformed faces to resemble birds, dogs, or goats.

De Lumley earlier co-authored a 72-page monograph for the Leonardo DNA Project: “Leonardo da Vinci: Pioneer of comparative anatomy, biomechanics and physiognomy.”.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper featuring microbes and art masterpiece,

Characterizing Microbial Signatures on Sculptures and Paintings of Similar Provenance by Manolito G. Torralba, Claire Kuelbs, Kelvin Jens Moncera, Rhonda Roby & Karen E. Nelson. Microbial Ecology (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-020-01504-x Published: 21 May 2020

This paper is open access.