The title, which I’ve borrowed from the news release, is the only Wizard of Oz reference that I can find but it works so well, you don’t really need anything more.

Moving onto the news, a July 23, 2018 news item on phys.org announces new work on developing an artificial synapse (Note: A link has been removed),

Digital computation has rendered nearly all forms of analog computation obsolete since as far back as the 1950s. However, there is one major exception that rivals the computational power of the most advanced digital devices: the human brain.

The human brain is a dense network of neurons. Each neuron is connected to tens of thousands of others, and they use synapses to fire information back and forth constantly. With each exchange, the brain modulates these connections to create efficient pathways in direct response to the surrounding environment. Digital computers live in a world of ones and zeros. They perform tasks sequentially, following each step of their algorithms in a fixed order.

A team of researchers from Pitt’s [University of Pittsburgh] Swanson School of Engineering have developed an “artificial synapse” that does not process information like a digital computer but rather mimics the analog way the human brain completes tasks. Led by Feng Xiong, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, the researchers published their results in the recent issue of the journal Advanced Materials (DOI: 10.1002/adma.201802353). His Pitt co-authors include Mohammad Sharbati (first author), Yanhao Du, Jorge Torres, Nolan Ardolino, and Minhee Yun.

A July 23, 2018 University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides further information,

“The analog nature and massive parallelism of the brain are partly why humans can outperform even the most powerful computers when it comes to higher order cognitive functions such as voice recognition or pattern recognition in complex and varied data sets,” explains Dr. Xiong.

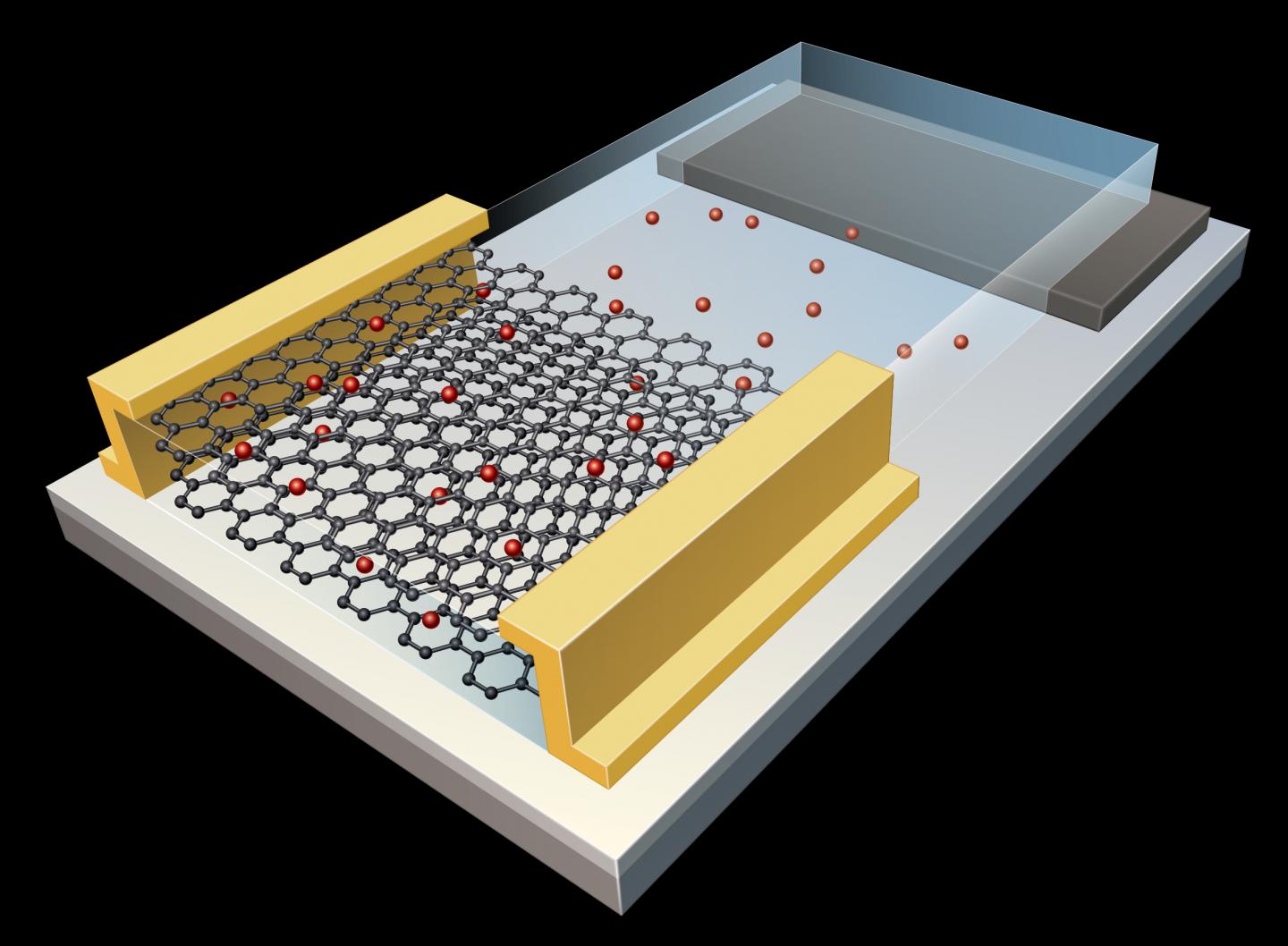

An emerging field called “neuromorphic computing” focuses on the design of computational hardware inspired by the human brain. Dr. Xiong and his team built graphene-based artificial synapses in a two-dimensional honeycomb configuration of carbon atoms. Graphene’s conductive properties allowed the researchers to finely tune its electrical conductance, which is the strength of the synaptic connection or the synaptic weight. The graphene synapse demonstrated excellent energy efficiency, just like biological synapses.

In the recent resurgence of artificial intelligence, computers can already replicate the brain in certain ways, but it takes about a dozen digital devices to mimic one analog synapse. The human brain has hundreds of trillions of synapses for transmitting information, so building a brain with digital devices is seemingly impossible, or at the very least, not scalable. Xiong Lab’s approach provides a possible route for the hardware implementation of large-scale artificial neural networks.

According to Dr. Xiong, artificial neural networks based on the current CMOS (complementary metal-oxide semiconductor) technology will always have limited functionality in terms of energy efficiency, scalability, and packing density. “It is really important we develop new device concepts for synaptic electronics that are analog in nature, energy-efficient, scalable, and suitable for large-scale integrations,” he says. “Our graphene synapse seems to check all the boxes on these requirements so far.”

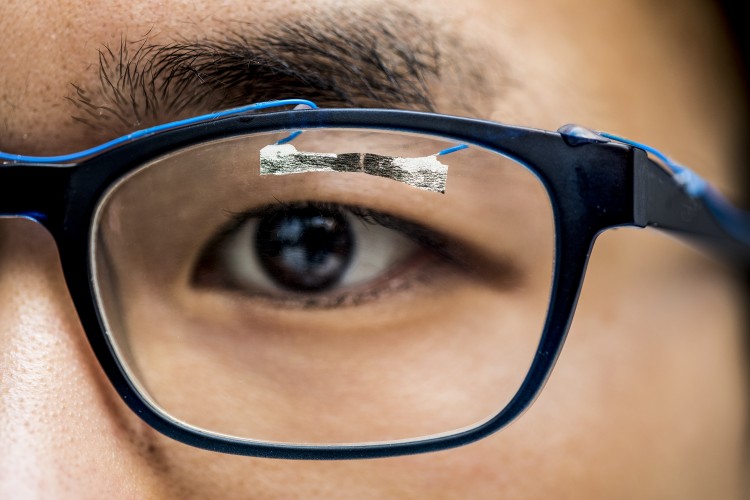

With graphene’s inherent flexibility and excellent mechanical properties, these graphene-based neural networks can be employed in flexible and wearable electronics to enable computation at the “edge of the internet”–places where computing devices such as sensors make contact with the physical world.

“By empowering even a rudimentary level of intelligence in wearable electronics and sensors, we can track our health with smart sensors, provide preventive care and timely diagnostics, monitor plants growth and identify possible pest issues, and regulate and optimize the manufacturing process–significantly improving the overall productivity and quality of life in our society,” Dr. Xiong says.

The development of an artificial brain that functions like the analog human brain still requires a number of breakthroughs. Researchers need to find the right configurations to optimize these new artificial synapses. They will need to make them compatible with an array of other devices to form neural networks, and they will need to ensure that all of the artificial synapses in a large-scale neural network behave in the same exact manner. Despite the challenges, Dr. Xiong says he’s optimistic about the direction they’re headed.

“We are pretty excited about this progress since it can potentially lead to the energy-efficient, hardware implementation of neuromorphic computing, which is currently carried out in power-intensive GPU clusters. The low-power trait of our artificial synapse and its flexible nature make it a suitable candidate for any kind of A.I. device, which would revolutionize our lives, perhaps even more than the digital revolution we’ve seen over the past few decades,” Dr. Xiong says.

There is a visual representation of this artificial synapse,

Caption: Pitt engineers built a graphene-based artificial synapse in a two-dimensional, honeycomb configuration of carbon atoms that demonstrated excellent energy efficiency comparable to biological synapses Credit: Swanson School of Engineering

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Low‐Power, Electrochemically Tunable Graphene Synapses for Neuromorphic Computing by Mohammad Taghi Sharbati, Yanhao Du, Jorge Torres, Nolan D. Ardolino, Minhee Yun, Feng Xiong. Advanced Materials DOP: https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201802353 First published [online]: 23 July 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.

I did look at the paper and if I understand it rightly, this approach is different from the memristor-based approaches that I have so often featured here. More than that I cannot say.

Finally, the Wizard of Oz song ‘If I Only Had a Brain’,