A February 23, 2021 news item on ScienceDaily announces work which may lead to healing brain injuries and diseases,

Imagine if surgeons could transplant healthy neurons into patients living with neurodegenerative diseases or brain and spinal cord injuries. And imagine if they could “grow” these neurons in the laboratory from a patient’s own cells using a synthetic, highly bioactive material that is suitable for 3D printing.

By discovering a new printable biomaterial that can mimic properties of brain tissue, Northwestern University researchers are now closer to developing a platform capable of treating these conditions using regenerative medicine.

…

A February 22, 2021 Northwestern University news release (also received by email and available on EurekAlert) by Lila Reynolds, which originated the news item, delves further into self-assembling ‘walking’ molecules and the nanofibers resulting in a new material designed to promote the growth of healthy neurons,

A key ingredient to the discovery is the ability to control the self-assembly processes of molecules within the material, enabling the researchers to modify the structure and functions of the systems from the nanoscale to the scale of visible features. The laboratory of Samuel I. Stupp published a 2018 paper in the journal Science which showed that materials can be designed with highly dynamic molecules programmed to migrate over long distances and self-organize to form larger, “superstructured” bundles of nanofibers.

Now, a research group led by Stupp has demonstrated that these superstructures can enhance neuron growth, an important finding that could have implications for cell transplantation strategies for neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, as well as spinal cord injury.

“This is the first example where we’ve been able to take the phenomenon of molecular reshuffling we reported in 2018 and harness it for an application in regenerative medicine,” said Stupp, the lead author on the study and the director of Northwestern’s Simpson Querrey Institute. “We can also use constructs of the new biomaterial to help discover therapies and understand pathologies.

…

Walking molecules and 3D printing

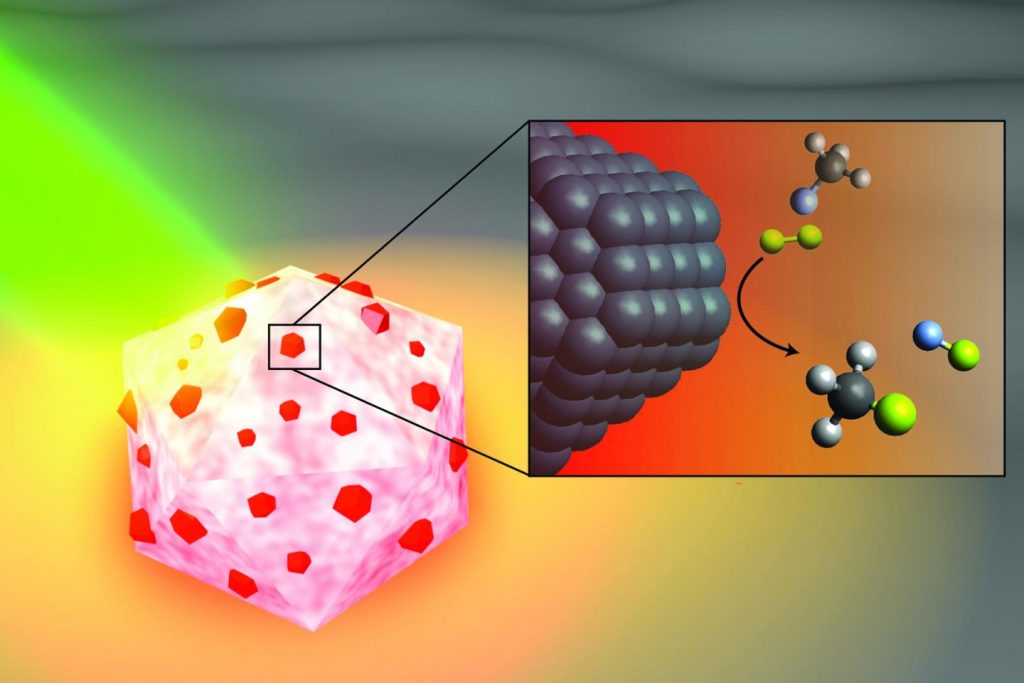

The new material is created by mixing two liquids that quickly become rigid as a result of interactions known in chemistry as host-guest complexes that mimic key-lock interactions among proteins, and also as the result of the concentration of these interactions in micron-scale regions through a long scale migration of “walking molecules.”

The agile molecules cover a distance thousands of times larger than themselves in order to band together into large superstructures. At the microscopic scale, this migration causes a transformation in structure from what looks like an uncooked chunk of ramen noodles into ropelike bundles.

“Typical biomaterials used in medicine like polymer hydrogels don’t have the capabilities to allow molecules to self-assemble and move around within these assemblies,” said Tristan Clemons, a research associate in the Stupp lab and co-first author of the paper with Alexandra Edelbrock, a former graduate student in the group. “This phenomenon is unique to the systems we have developed here.”

Furthermore, as the dynamic molecules move to form superstructures, large pores open that allow cells to penetrate and interact with bioactive signals that can be integrated into the biomaterials.

Interestingly, the mechanical forces of 3D printing disrupt the host-guest interactions in the superstructures and cause the material to flow, but it can rapidly solidify into any macroscopic shape because the interactions are restored spontaneously by self-assembly. This also enables the 3D printing of structures with distinct layers that harbor different types of neural cells in order to study their interactions.

Signaling neuronal growth

The superstructure and bioactive properties of the material could have vast implications for tissue regeneration. Neurons are stimulated by a protein in the central nervous system known as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which helps neurons survive by promoting synaptic connections and allowing neurons to be more plastic. BDNF could be a valuable therapy for patients with neurodegenerative diseases and injuries in the spinal cord but these proteins degrade quickly in the body and are expensive to produce.

One of the molecules in the new material integrates a mimic of this protein that activates its receptor known as Trkb, and the team found that neurons actively penetrate the large pores and populate the new biomaterial when the mimetic signal is present. This could also create an environment in which neurons differentiated from patient-derived stem cells mature before transplantation.

Now that the team has applied a proof of concept to neurons, Stupp believes he could now break into other areas of regenerative medicine by applying different chemical sequences to the material. Simple chemical changes in the biomaterials would allow them to provide signals for a wide range of tissues.

“Cartilage and heart tissue are very difficult to regenerate after injury or heart attacks, and the platform could be used to prepare these tissues in vitro from patient-derived cells,” Stupp said. “These tissues could then be transplanted to help restore lost functions. Beyond these interventions, the materials could be used to build organoids to discover therapies or even directly implanted into tissues for regeneration since they are biodegradable.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Superstructured Biomaterials Formed by Exchange Dynamics and Host–Guest Interactions in Supramolecular Polymers by Alexandra N. Edelbrock, Tristan D. Clemons, Stacey M. Chin, Joshua J. W. Roan, Eric P. Bruckner, Zaida Álvarez, Jack F. Edelbrock, Kristen S. Wek, Samuel I. Stupp. Advanced Science DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202004042 First published: 22 February 2021

This paper is open access.