Both of these news bits are concerned with light for one reason or another.

Rice University (Texas, US) and breaking fluorocarbon bonds

The secret to breaking fluorocarbon bonds is light according to a June 22, 2020 news item on Nanowerk,

Rice University engineers have created a light-powered catalyst that can break the strong chemical bonds in fluorocarbons, a group of synthetic materials that includes persistent environmental pollutants.

…

A June 22, 2020 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the work in greater detail,

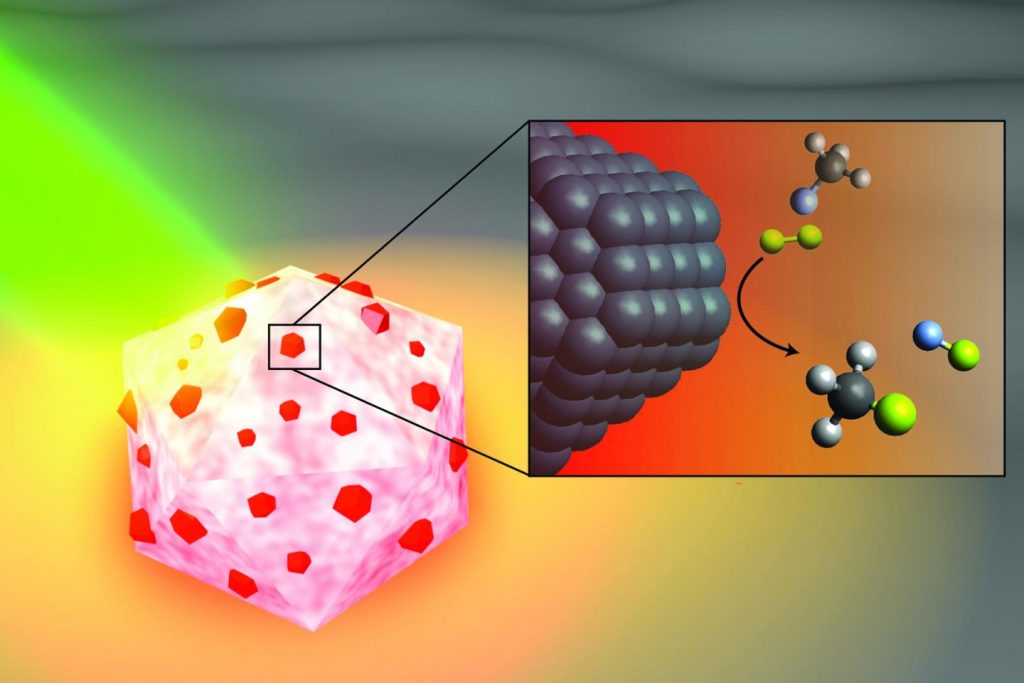

In a study published this month in Nature Catalysis, Rice nanophotonics pioneer Naomi Halas and collaborators at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) and Princeton University showed that tiny spheres of aluminum dotted with specks of palladium could break carbon-fluorine (C-F) bonds via a catalytic process known as hydrodefluorination in which a fluorine atom is replaced by an atom of hydrogen.

The strength and stability of C-F bonds are behind some of the 20th century’s most recognizable chemical brands, including Teflon, Freon and Scotchgard. But the strength of those bonds can be problematic when fluorocarbons get into the air, soil and water. Chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, for example, were banned by international treaty in the 1980s after they were found to be destroying Earth’s protective ozone layer, and other fluorocarbons were on the list of “forever chemicals” targeted by a 2001 treaty.

“The hardest part about remediating any of the fluorine-containing compounds is breaking the C-F bond; it requires a lot of energy,” said Halas, an engineer and chemist whose Laboratory for Nanophotonics (LANP) specializes in creating and studying nanoparticles that interact with light.

Over the past five years, Halas and colleagues have pioneered methods for making “antenna-reactor” catalysts that spur or speed up chemical reactions. While catalysts are widely used in industry, they are typically used in energy-intensive processes that require high temperature, high pressure or both. For example, a mesh of catalytic material is inserted into a high-pressure vessel at a chemical plant, and natural gas or another fossil fuel is burned to heat the gas or liquid that’s flowed through the mesh. LANP’s antenna-reactors dramatically improve energy efficiency by capturing light energy and inserting it directly at the point of the catalytic reaction.

In the Nature Catalysis study, the energy-capturing antenna is an aluminum particle smaller than a living cell, and the reactors are islands of palladium scattered across the aluminum surface. The energy-saving feature of antenna-reactor catalysts is perhaps best illustrated by another of Halas’ previous successes: solar steam. In 2012, her team showed its energy-harvesting particles could instantly vaporize water molecules near their surface, meaning Halas and colleagues could make steam without boiling water. To drive home the point, they showed they could make steam from ice-cold water.

The antenna-reactor catalyst design allows Halas’ team to mix and match metals that are best suited for capturing light and catalyzing reactions in a particular context. The work is part of the green chemistry movement toward cleaner, more efficient chemical processes, and LANP has previously demonstrated catalysts for producing ethylene and syngas and for splitting ammonia to produce hydrogen fuel.

Study lead author Hossein Robatjazi, a Beckman Postdoctoral Fellow at UCSB who earned his Ph.D. from Rice in 2019, conducted the bulk of the research during his graduate studies in Halas’ lab. He said the project also shows the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration.

“I finished the experiments last year, but our experimental results had some interesting features, changes to the reaction kinetics under illumination, that raised an important but interesting question: What role does light play to promote the C-F breaking chemistry?” he said.

The answers came after Robatjazi arrived for his postdoctoral experience at UCSB. He was tasked with developing a microkinetics model, and a combination of insights from the model and from theoretical calculations performed by collaborators at Princeton helped explain the puzzling results.

“With this model, we used the perspective from surface science in traditional catalysis to uniquely link the experimental results to changes to the reaction pathway and reactivity under the light,” he said.

The demonstration experiments on fluoromethane could be just the beginning for the C-F breaking catalyst.

“This general reaction may be useful for remediating many other types of fluorinated molecules,” Halas said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Plasmon-driven carbon–fluorine (C(sp3)–F) bond activation with mechanistic insights into hot-carrier-mediated pathways by Hossein Robatjazi, Junwei Lucas Bao, Ming Zhang, Linan Zhou, Phillip Christopher, Emily A. Carter, Peter Nordlander & Naomi J. Halas. Nature Catalysis (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-020-0466-5 Published: 08 June 2020

This paper is behind a paywall.

Northwestern University (Illinois, US) brings soft robots to ‘life’

This June 22, 2020 news item on ScienceDaily reveals how scientists are getting soft robots to mimic living creatures,

Northwestern University researchers have developed a family of soft materials that imitates living creatures.

When hit with light, the film-thin materials come alive — bending, rotating and even crawling on surfaces.

…

A June 22, 2020 Northwestern University news release (also on EurekAlert) by Amanda Morris, which originated the news item, delves further into the details,

Called “robotic soft matter by the Northwestern team,” the materials move without complex hardware, hydraulics or electricity. The researchers believe the lifelike materials could carry out many tasks, with potential applications in energy, environmental remediation and advanced medicine.

“We live in an era in which increasingly smarter devices are constantly being developed to help us manage our everyday lives,” said Northwestern’s Samuel I. Stupp, who led the experimental studies. “The next frontier is in the development of new science that will bring inert materials to life for our benefit — by designing them to acquire capabilities of living creatures.”

The research will be published on June 22 [2020] in the journal Nature Materials.

Stupp is the Board of Trustees Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Chemistry, Medicine and Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern and director of the Simpson Querrey Institute He has appointments in the McCormick School of Engineering, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and Feinberg School of Medicine. George Schatz, the Charles E. and Emma H. Morrison Professor of Chemistry in Weinberg, led computer simulations of the materials’ lifelike behaviors. Postdoctoral fellow Chuang Li and graduate student Aysenur Iscen, from the Stupp and Schatz laboratories, respectively, are co-first authors of the paper.

Although the moving material seems miraculous, sophisticated science is at play. Its structure comprises nanoscale peptide assemblies that drain water molecules out of the material. An expert in materials chemistry, Stupp linked the peptide arrays to polymer networks designed to be chemically responsive to blue light.

When light hits the material, the network chemically shifts from hydrophilic (attracts water) to hydrophobic (resists water). As the material expels the water through its peptide “pipes,” it contracts — and comes to life. When the light is turned off, water re-enters the material, which expands as it reverts to a hydrophilic structure.

This is reminiscent of the reversible contraction of muscles, which inspired Stupp and his team to design the new materials.

“From biological systems, we learned that the magic of muscles is based on the connection between assemblies of small proteins and giant protein polymers that expand and contract,” Stupp said. “Muscles do this using a chemical fuel rather than light to generate mechanical energy.”

For Northwestern’s bio-inspired material, localized light can trigger directional motion. In other words, bending can occur in different directions, depending on where the light is located. And changing the direction of the light also can force the object to turn as it crawls on a surface.

Stupp and his team believe there are endless possible applications for this new family of materials. With the ability to be designed in different shapes, the materials could play a role in a variety of tasks, ranging from environmental clean-up to brain surgery.

“These materials could augment the function of soft robots needed to pick up fragile objects and then release them in a precise location,” he said. “In medicine, for example, soft materials with ‘living’ characteristics could bend or change shape to retrieve blood clots in the brain after a stroke. They also could swim to clean water supplies and sea water or even undertake healing tasks to repair defects in batteries, membranes and chemical reactors.”

Fascinating, eh? No batteries, no power source, just light to power movement. For the curious, here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Supramolecular–covalent hybrid polymers for light-activated mechanical actuation by Chuang Li, Aysenur Iscen, Hiroaki Sai, Kohei Sato, Nicholas A. Sather, Stacey M. Chin, Zaida Álvarez, Liam C. Palmer, George C. Schatz & Samuel I. Stupp. Nature Materials (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-0707-7 Published: 22 June 2020

This paper is behind a paywall.