The ‘pair of scissors’ analogy is probably the most well known of the attempts to describe how the CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)-Cas9 gene editing system works. It seems a new analogy is about to be added according to a January 19 2021 news item on ScienceDaily (Note: This October 30, 2019 posting features more CRISPR analogies),

In a series of experiments with laboratory-cultured bacteria, Johns Hopkins scientists have found evidence that there is a second role for the widely used gene-cutting system CRISPR-Cas9 — as a genetic dimmer switch for CRISPR-Cas9 genes. Its role of dialing down or dimming CRISPR-Cas9 activity may help scientists develop new ways to genetically engineer cells for research purposes.

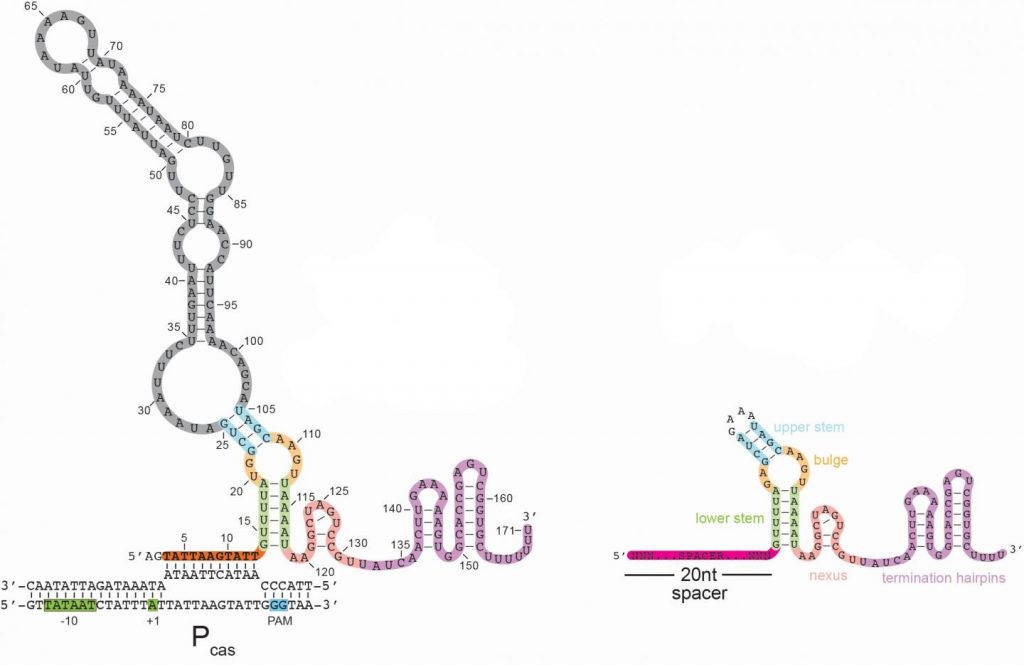

Here’s an image illustrating the long form of the tracrRNA or ‘dimmer switch’ alongside the more commonly used short form,

A January 19 ,2021 Johns Hopkins Medicine news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, explains about CRISPR and what the acronym stands for, as well as, giving more details about the discovery,

First identified in the genome of gut bacteria in 1987, CRISPR-Cas9 is a naturally occurring but unusual group of genes with a potential for cutting DNA sequences in other types of cells that was realized 25 years later. Its value in genetic engineering — programmable gene alteration in living cells, including human cells — was rapidly appreciated, and its widespread use as a genome “editor” in thousands of laboratories worldwide was recognized in the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry last year to its American and French co-developers.

CRISPR stands for clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Cas9, which refers to CRISPR-associated protein 9, is the name of the enzyme that makes the DNA slice. Bacteria naturally use CRISPR-Cas9 to cut viral or other potentially harmful DNA and disable the threat, says Joshua Modell, Ph.D., assistant professor of molecular biology and genetics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. In this role, Modell says, “CRISPR is not only an immune system, it’s an adaptive immune system — one that can remember threats it has previously encountered by holding onto a short piece of their DNA, which is akin to a mug shot.” These mug shots are then copied into “guide RNAs” that tell Cas9 what to cut.

Scientists have long worked to unravel the precise steps of CRISPR-Cas9’s mechanism and how its activity in bacteria is dialed up or down. Looking for genes that ignite or inhibit the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-cutting system for the common, strep-throat causing bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes, the Johns Hopkins scientists found a clue regarding how that aspect of the system works.

Specifically, the scientists found a gene in the CRISPR-Cas9 system that, when deactivated, led to a dramatic increase in the activity of the system in bacteria. The product of this gene appeared to re-program Cas9 to act as a brake, rather than as a “scissor,” to dial down the CRISPR system.

“From an immunity perspective, bacteria need to ramp up CRISPR-Cas9 activity to identify and rid the cell of threats, but they also need to dial it down to avoid autoimmunity — when the immune system mistakenly attacks components of the bacteria themselves,” says graduate student Rachael Workman, a bacteriologist working in Modell’s laboratory.

To further nail down the particulars of the “brake,” the team’s next step was to better understand the product of the deactivated gene (tracrRNA). RNA is a genetic cousin to DNA and is vital to carrying out DNA “instructions” for making proteins. TracrRNAs belong to a unique family of RNAs that do not make proteins. Instead, they act as a kind of scaffold that allows the Cas9 enzyme to carry the guide RNA that contains the mug shot and cut matching DNA sequences in invading viruses.

TracrRNA comes in two sizes: long and short. Most of the modern gene-cutting CRISPR-Cas9 tools use the short form. However, the research team found that the deactivated gene product was the long form of tracrRNA, the function of which has been entirely unknown.

The long and short forms of tracrRNA are similar in structure and have in common the ability to bind to Cas9. The short form tracrRNA also binds to the guide RNA. However, the long form tracrRNA doesn’t need to bind to the guide RNA, because it contains a segment that mimics the guide RNA. “Essentially, long form tracrRNAs have combined the function of the short form tracrRNA and guide RNA,” says Modell.

In addition, the researchers found that while guide RNAs normally seek out viral DNA sequences, long form tracrRNAs target the CRISPR-Cas9 system itself. The long form tracrRNA tends to sit on DNA, rather than cut it. When this happens in a particular area of a gene, it prevents that gene from expressing, — or becoming functional.

To confirm this, the researchers used genetic engineering to alter the length of a certain region in long form tracrRNA to make the tracrRNA appear more like a guide RNA. They found that with the altered long form tracrRNA, Cas9 once again behaved more like a scissor.

Other experiments showed that in lab-grown bacteria with a plentiful amount of long form tracrRNA, levels of all CRISPR-related genes were very low. When the long form tracrRNA was removed from bacteria, however, expression of CRISPR-Cas9 genes increased a hundredfold.

Bacterial cells lacking the long form tracrRNA were cultured in the laboratory for three days and compared with similarly cultured cells containing the long form tracrRNA. By the end of the experiment, bacteria without the long form tracrRNA had completely died off, suggesting that long form tracrRNA normally protects cells from the sickness and death that happen when CRISPR-Cas9 activity is very high.

“We started to get the idea that the long form was repressing but not eliminating its own CRISPR-related activity,” says Workman.

To see if the long form tracrRNA could be re-programmed to repress other bacterial genes, the research team altered the long form tracrRNA’s spacer region to let it sit on a gene that produces green fluorescence. Bacteria with this mutated version of long form tracrRNA glowed less green than bacteria containing the normal long form tracrRNA, suggesting that the long form tracrRNA can be genetically engineered to dial down other bacterial genes.

Another research team, from Emory University, found that in the parasitic bacteria Francisella novicida, Cas9 behaves as a dimmer switch for a gene outside the CRISPR-Cas9 region. The CRISPR-Cas9 system in the Johns Hopkins study is more widely used by scientists as a gene-cutting tool, and the Johns Hopkins team’s findings provide evidence that the dimmer action controls the CRISPR-Cas9 system in addition to other genes.

The researchers also found the genetic components of long form tracrRNA in about 40% of the Streptococcus group of bacteria. Further study of bacterial strains that don’t have the long form tracrRNA, says Workman, will potentially reveal whether their CRISPR-Cas9 systems are intact, and other ways that bacteria may dial back the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

The dimmer capability that the experiments uncovered, says Modell, offers opportunities to design new or better CRISPR-Cas9 tools aimed at regulating gene activity for research purposes. “In a gene editing scenario, a researcher may want to cut a specific gene, in addition to using the long form tracrRNA to inhibit gene activity,” he says.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A natural single-guide RNA repurposes Cas9 to autoregulate CRISPR-Cas expression by Rachael E. Workman, Teja Pammi, Binh T.K. Nguyen, Leonardo W. Graeff, Erika Smith, Suzanne M. Sebald, Marie J. Stoltzfus, Chad W. Euler, Joshua W. Modell. Cell DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.017 Published Online:J anuary 08, 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.