This post was going to be about new research into fetal therapeutics and mRNA.But, since I’ve been very intrigued by the therapeutic agent, mRNA, which has been a big part of the COVID-19 vaccine story; this seemed like a good opportunity to dive a little more deeply into that topic at the same time.

It’s called messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and until seeing this video I had only the foggiest idea of how it works, which is troubling since at least two COVID-19 vaccines are based on this ‘new’ technology. From a November 10, 2020 article by Damian Garde for STAT,

Garde’s article offers detail about mRNA along with fascinating insight into how science and entreneurship works.

mRNA—it’s in the details, plus, the loneliness of pioneer researchers, a demotion, and squabbles

Garde’s November 10, 2020 article provides some explanation about how mRNA vaccines work and it takes a look at what can happen to pioneering scientists (Note: A link has been removed),

For decades, scientists have dreamed about the seemingly endless possibilities of custom-made messenger RNA, or mRNA.

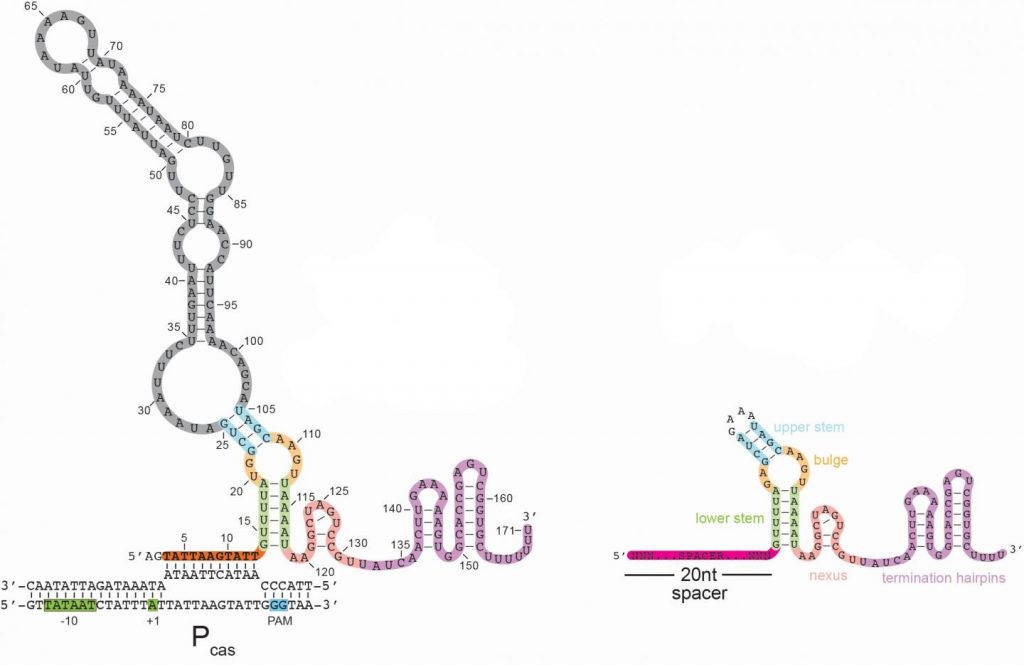

Researchers understood its role as a recipe book for the body’s trillions of cells, but their efforts to expand the menu have come in fits and starts. The concept: By making precise tweaks to synthetic mRNA and injecting people with it, any cell in the body could be transformed into an on-demand drug factory. [emphasis mine]

But turning scientific promise into medical reality has been more difficult than many assumed. Although relatively easy and quick to produce compared to traditional vaccine-making, no mRNA vaccine or drug has ever won approval [until 2021].

…

Whether mRNA vaccines succeed or not, their path from a gleam in a scientist’s eye to the brink of government approval has been a tale of personal perseverance, eureka moments in the lab, soaring expectations — and an unprecedented flow of cash into the biotech industry.

…

Before messenger RNA was a multibillion-dollar idea, it was a scientific backwater. And for the Hungarian-born scientist behind a key mRNA discovery, it was a career dead-end.

Katalin Karikó spent the 1990s collecting rejections. Her work, attempting to harness the power of mRNA to fight disease, was too far-fetched for government grants, corporate funding, and even support from her own colleagues.

It all made sense on paper. In the natural world, the body relies on millions of tiny proteins to keep itself alive and healthy, and it uses mRNA to tell cells which proteins to make. If you could design your own mRNA, you could, in theory, hijack that process and create any protein you might desire — antibodies to vaccinate against infection, enzymes to reverse a rare disease, or growth agents to mend damaged heart tissue.

In 1990, researchers at the University of Wisconsin managed to make it work in mice. Karikó wanted to go further.

The problem, she knew, was that synthetic RNA was notoriously vulnerable to the body’s natural defenses, meaning it would likely be destroyed before reaching its target cells. And, worse, the resulting biological havoc might stir up an immune response that could make the therapy a health risk for some patients.

It was a real obstacle, and still may be, but Karikó was convinced it was one she could work around. Few shared her confidence.

“Every night I was working: grant, grant, grant,” Karikó remembered, referring to her efforts to obtain funding. “And it came back always no, no, no.”

By 1995, after six years on the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikó got demoted. She had been on the path to full professorship, but with no money coming in to support her work on mRNA, her bosses saw no point in pressing on.

She was back to the lower rungs of the scientific academy.

“Usually, at that point, people just say goodbye and leave because it’s so horrible,” Karikó said.

There’s no opportune time for demotion, but 1995 had already been uncommonly difficult. Karikó had recently endured a cancer scare, and her husband was stuck in Hungary sorting out a visa issue. Now the work to which she’d devoted countless hours was slipping through her fingers.

“I thought of going somewhere else, or doing something else,” Karikó said. “I also thought maybe I’m not good enough, not smart enough. I tried to imagine: Everything is here, and I just have to do better experiments.”

In time, those better experiments came together. After a decade of trial and error, Karikó and her longtime collaborator at Penn — Drew Weissman, an immunologist with a medical degree and Ph.D. from Boston University — discovered a remedy for mRNA’s Achilles’ heel.

The stumbling block, as Karikó’s many grant rejections pointed out, was that injecting synthetic mRNA typically led to that vexing immune response; the body sensed a chemical intruder, and went to war. The solution, Karikó and Weissman discovered, was the biological equivalent of swapping out a tire.

Every strand of mRNA is made up of four molecular building blocks called nucleosides. But in its altered, synthetic form, one of those building blocks, like a misaligned wheel on a car, was throwing everything off by signaling the immune system. So Karikó and Weissman simply subbed it out for a slightly tweaked version, creating a hybrid mRNA that could sneak its way into cells without alerting the body’s defenses.

“That was a key discovery,” said Norbert Pardi, an assistant professor of medicine at Penn and frequent collaborator. “Karikó and Weissman figured out that if you incorporate modified nucleosides into mRNA, you can kill two birds with one stone.”

That discovery, described in a series of scientific papers starting in 2005, largely flew under the radar at first, said Weissman, but it offered absolution to the mRNA researchers who had kept the faith during the technology’s lean years. And it was the starter pistol for the vaccine sprint to come.

…

Entrepreneurs rush in

Garde’s November 10, 2020 article shifts focus from Karikó, Weissman, and specifics about mRNA to the beginnings of what might be called an entrepreneurial gold rush although it starts sedately,

Derrick Rossi [emphasis mine], a native of Toronto who rooted for the Maple Leafs and sported a soul patch, was a 39-year-old postdoctoral fellow in stem cell biology at Stanford University in 2005 when he read the first paper. Not only did he recognize it as groundbreaking, he now says Karikó and Weissman deserve the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

“If anyone asks me whom to vote for some day down the line, I would put them front and center,” he said. “That fundamental discovery is going to go into medicines that help the world.”

But Rossi didn’t have vaccines on his mind when he set out to build on their findings in 2007 as a new assistant professor at Harvard Medical School running his own lab.

He wondered whether modified messenger RNA might hold the key to obtaining something else researchers desperately wanted: a new source of embryonic stem cells [emphasis mine].

In a feat of biological alchemy, embryonic stem cells can turn into any type of cell in the body. That gives them the potential to treat a dizzying array of conditions, from Parkinson’s disease to spinal cord injuries.

But using those cells for research had created an ethical firestorm because they are harvested from discarded embryos.

Rossi thought he might be able to sidestep the controversy. He would use modified messenger molecules to reprogram adult cells so that they acted like embryonic stem cells.

He asked a postdoctoral fellow in his lab to explore the idea. In 2009, after more than a year of work, the postdoc waved Rossi over to a microscope. Rossi peered through the lens and saw something extraordinary: a plate full of the very cells he had hoped to create.

Rossi excitedly informed his colleague Timothy Springer, another professor at Harvard Medical School and a biotech entrepreneur. Recognizing the commercial potential, Springer contacted Robert Langer, the prolific inventor and biomedical engineering professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

On a May afternoon in 2010, Rossi and Springer visited Langer at his laboratory in Cambridge. What happened at the two-hour meeting and in the days that followed has become the stuff of legend — and an ego-bruising squabble.

Langer is a towering figure in biotechnology and an expert on drug-delivery technology. At least 400 drug and medical device companies have licensed his patents. His office walls display many of his 250 major awards, including the Charles Stark Draper Prize, considered the equivalent of the Nobel Prize for engineers.

As he listened to Rossi describe his use of modified mRNA, Langer recalled, he realized the young professor had discovered something far bigger than a novel way to create stem cells. Cloaking mRNA so it could slip into cells to produce proteins had a staggering number of applications, Langer thought, and might even save millions of lives.

“I think you can do a lot better than that,” Langer recalled telling Rossi, referring to stem cells. “I think you could make new drugs, new vaccines — everything.”

…

Within several months, Rossi, Langer, Afeyan [Noubar Afeyan, venture capitalist, founded and runs Flagship Ventures], and another physician-researcher at Harvard formed the firm Moderna — a new word combining modified and RNA.

Springer was the first investor to pledge money, Rossi said. In a 2012 Moderna news release, Afeyan said the firm’s “promise rivals that of the earliest biotechnology companies over 30 years ago — adding an entirely new drug category to the pharmaceutical arsenal.”

But although Moderna has made each of the founders hundreds of millions of dollars — even before the company had produced a single product — Rossi’s account is marked by bitterness. In interviews with the [Boston] Globe in October [2020], he accused Langer and Afeyan of propagating a condescending myth that he didn’t understand his discovery’s full potential until they pointed it out to him.

…

Garde goes on to explain how BioNTech came into the mRNA picture and contrasts the two companies’ approaches to biotechnology as a business. It seems BioNTech has not cashed in the same way as has Moderna. (For some insight into who’s making money from COVID-19 check out Giacomo Tognini’s December 23, 2020 article (Meet The 50 Doctors, Scientists And Healthcare Entrepreneurs Who Became Pandemic Billionaires In 2020) for Forbes.)

Garde ends his November 10, 2020 article on a mildly cautionary note,

“You have all these odd clinical and pathological changes caused by this novel bat coronavirus [emphasis mine], and you’re about to meet it with all of these vaccines with which you have no experience,” said Paul Offit, an infectious disease expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and an authority on vaccines.

What happened to Katalin Karikó?

Matthew Rosza’s January 25, 2021 article about Karikó and her pioneering work features an answer to my question and some advice,

“I want young people to feel — if my example, because I was demoted, rejected, terminated, I was even subject for deportation one point — [that] if they just pursue their thing, my example helps them to wear rejection as a badge,” Karikó, who today is a senior vice president at BioNTech RNA Pharmaceuticals, told Salon last month when discussing her story. “‘Okay, well, I was rejected. I know. Katalin was rejected and still [succeeded] at the end.’ So if it helps them, then it helps them.”

Despite her demotion, Karikó continued with her work and, along with a fellow immunologist named Dr. Drew Weissman, penned a series of influential articles starting in 2005. These articles argued that mRNA vaccines would not be neutralized by the human immune system as long as there were specific modifications to nucleosides, a compound commonly found in RNA.

By 2013, Karikó’s work had sufficiently impressed experts that she left the University of Pennsylvania for BioNTech RNA Pharmaceuticals.

Karikó tells Salon that the experience taught her one important lesson: In life there will be people who, for various reasons, will try to hold you back, and you can’t let them get you down.

“People that are in power, they can help you or block you,” Karikó told Salon. “And sometimes people select to make your life miserable. And now they cannot be happy with me because now they know that, ‘Oh, you know, we had the confrontation and…’ But I don’t spend too much time on these things.”

…

Before moving onto the genetic research which prompted this posting, I have an answer to the following questions:

Could an mRNA vaccine affect your DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and how do mRNA vaccines differ from the traditional ones?

No, DNA is not affected by the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, according to a January 5, 2021 article by Jason Murdock for Newsweek,

The type of vaccines used against COVID-19 do not interact with or alter human genetic code, also known as DNA, scientists say.

…

In traditional vaccines, a piece of a virus, known as an “antigen,” would be injected into the body to force the immune system to make antibodies to fight off future infection. But mRNA-based methods do not use a live virus, and cannot give someone COVID.

Instead, mRNA vaccines give cells the instructions to make a “spike” protein also found on the surface of the virus that causes COVID. The body kickstarts its immune response by creating the antibodies needed to combat those specific virus proteins.

Once the spike protein is created, the cell breaks down the instructions provided by the mRNA molecule, leaving the human immune system prepared to combat infection. The mRNA vaccines are not a medicine—nor a cure—but a preventative measure.

Gavi, a vaccine alliance partnered with the World Health Organization (WHO), has said that mRNA instructions will become degraded in approximately 72 hours.

It says mRNA strands are “chemical intermediaries” between DNA in our chromosomes and the “cellular machinery that produces the proteins we need to function.”

But crucially, while mRNA vaccines will give the human body the blueprints on how to assemble proteins, the alliance said in a fact-sheet last month that “mRNA isn’t the same as DNA, and it can’t combine with our DNA to change our genetic code.”

It explained: “Some viruses like HIV can integrate their genetic material into the DNA of their hosts, but this isn’t true of all viruses… mRNA vaccines don’t carry these enzymes, so there is no risk of the genetic material they contain altering our DNA.”

The [US] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says on its website that mRNA vaccines that are rolling out don’t “interact with our DNA in any way,” and “mRNA never enters the nucleus of the cell, which is where our DNA (genetic material) is kept.”

…

Therapeutic fetal mRNA treatment

Rossi’s work on mRNA and embryonic stem cells bears a relationship of sorts to this work focusing on prebirth therapeutics. (From a January 13, 2021 news item on Nanowerk), Note: A link has been removed,

Researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the School of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Pennsylvania have identified ionizable lipid nanoparticles that could be used to deliver mRNA as part of fetal therapy.

The proof-of-concept study, published in Science Advances (“Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticles for In Utero mRNA Delivery”), engineered and screened a number of lipid nanoparticle formulations for targeting mouse fetal organs and has laid the groundwork for testing potential therapies to treat genetic diseases before birth.

…

A January 13, 2021 Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves further into the research,

“This is an important first step in identifying nonviral mediated approaches for delivering cutting-edge therapies before birth,” said co-senior author William H. Peranteau, MD, an attending surgeon in the Division of General, Thoracic and Fetal Surgery and the Adzick-McCausland Distinguished Chair in Fetal and Pediatric Surgery at CHOP. “These lipid nanoparticles may provide a platform for in utero mRNA delivery, which would be used in therapies like fetal protein replacement and gene editing.”

…

Recent advances in DNA sequencing technology and prenatal diagnostics have made it possible to diagnose many genetic diseases before birth. Some of these diseases are treated by protein or enzyme replacement therapies after birth, but by then, some of the damaging effects of the disease have taken hold. Thus, applying therapies while the patient is still in the womb has the potential to be more effective for some conditions. The small fetal size allows for maximal therapeutic dosing, and the immature fetal immune system may be more tolerant of replacement therapy.

Of the potential vehicles for introducing therapeutic protein replacement, mRNA is distinct from other nucleic acids, such as DNA, because it does not need to enter the nucleus and can use the body’s own machinery to produce the desired proteins. Currently, the common methods of nucleic acid delivery include viral vectors and nonviral approaches. Although viral vectors may be well-suited to gene therapy, they come with the potential risk of unwanted integration of the transgene or parts of the viral vector in the recipient genome. Thus, there is an important need to develop safe and effective nonviral nucleic acid delivery technologies to treat prenatal diseases.

In order to identify potential nonviral delivery systems for therapeutic mRNA, the researchers engineered a library of lipid nanoparticles, small particles less than 100 nanometers in size that effectively enter cells in mouse fetal recipients. Each lipid nanoparticle formulation was used to encapsulate mRNA, which was administered to mouse fetuses. The researchers found that several of the lipid nanoparticles enabled functional mRNA delivery to fetal livers and that some of those lipid nanoparticles also delivered mRNA to the fetal lungs and intestines. They also assessed the lipid nanoparticles for toxicity and found them to be as safe or safer than existing formulations.

Having identified the lipid nanoparticles that were able to accumulate within fetal livers, lungs, and intestines with the highest efficiency and safety, the researchers also tested therapeutic potential of those designs by using them to deliver erythropoietin (EPO) mRNA, as the EPO protein is easily trackable. They found that EPO mRNA delivery to liver cells in mouse fetuses resulted in elevated levels of EPO protein in the fetal circulation, providing a model for protein replacement therapy via the liver using these lipid nanoparticles.

“A central challenge in the field of gene therapy is the delivery of nucleic acids to target cells and tissues, without causing side effects in healthy tissue. This is difficult to achieve in adult animals and humans, which have been studied extensively. Much less is known in terms of what is required to achieve in utero nucleic acid delivery,” said Mitchell. “We are very excited by the initial results of our lipid nanoparticle technology to deliver mRNA in utero in safe and effective manner, which could open new avenues for lipid nanoparticles and mRNA therapeutics to treat diseases before birth.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ionizable lipid nanoparticles for in utero mRNA delivery by Rachel S. Riley, Meghana V. Kashyap, Margaret M. Billingsley, Brandon White, Mohamad-Gabriel Alameh, Sourav K. Bose, Philip W. Zoltick, Hiaying Li, Rui Zhang, Andrew Y. Cheng, Drew Weissman, William H. Peranteau, Michael J. Mitchell. Science Advances 13 Jan 2021: Vol. 7, no. 3, eaba1028 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1028

This paper appears to be open access. BTW, I noticed Drew Weissman’s name as one of the paper’s authors and remembered him as one of the first to recognize Karikó’s pioneering work. I imagine that when he co-authored papers with Karikó he was risking his reputation.

Funny how a despised field of research has sparked a ‘gold rush’ for research and for riches, yes?.