A Sept. 13, 2016 news item on Nanowerk describes the database,

Nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego [UCSD], in collaboration with the Materials Project at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), have created the world’s largest database of elemental crystal surfaces and shapes to date. Dubbed Crystalium, this new open-source database can help researchers design new materials for technologies in which surfaces and interfaces play an important role, such as fuel cells, catalytic converters in cars, computer microchips, nanomaterials and solid-state batteries.

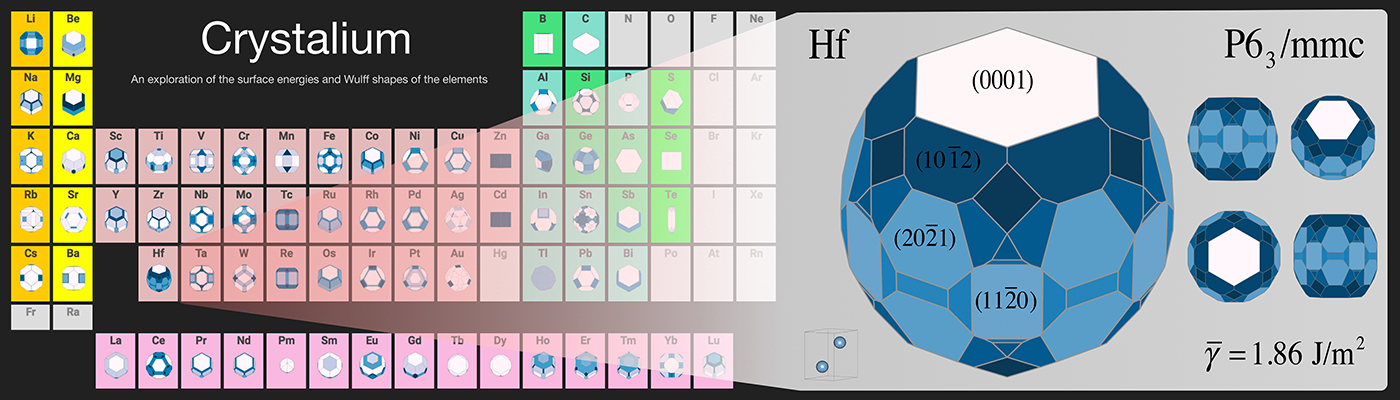

Crystalium is a new open-source database with the largest collection of elemental crystal surfaces and shapes to date. Image courtesy of the Materials Virtual Lab at UC San Diego

A Sept. 13, 2016 UCSD news release reveals more about the goals for the database and the database itself (Note: Links have been removed),

“This work is an important starting point for studying the material surfaces and interfaces, where many novel properties can be found. We’ve developed a new resource that can be used to better understand surface science and find better materials for surface-driven technologies,” said Shyue Ping Ong, a nanoengineering professor at UC San Diego and senior author of the study.

For example, fuel cell performance is partly influenced by the reaction of molecules such as hydrogen and oxygen on the surfaces of metal catalysts. Also, interfaces between the electrodes and electrolyte in a rechargeable lithium-ion battery host a variety of chemical reactions that can limit the battery’s performance. The work in this study is useful for these applications, said Ong, who is also part of a larger effort by the UC San Diego Sustainable Power and Energy Center to design better battery materials.

“Researchers can use this database to figure out which elements or materials are more likely to be viable catalysts for processes like ammonia production or making hydrogen gas from water,” said Richard Tran, a nanoengineering PhD student in Ong’s Materials Virtual Lab and the study’s first author. Tran did this work while he was an undergraduate at UC San Diego.

The work, published Sept. 13 [2016] in the journal Scientific Data, provides the surface energies and equilibrium crystal shapes of more than 100 polymorphs of 72 elements in the periodic table. Surface energy describes the stability of a surface; it is a measure of the excess energy of atoms on the surface relative to those in the bulk material. Knowing surface energies is useful for designing materials that perform their functions primarily on their surfaces, like catalysts and nanoparticles.

The surface energies of some elements in their crystal form have been measured experimentally, but this is not a trivial task. It involves melting the crystal, measuring the resulting liquid’s surface tension at the melting temperature, then extrapolating that value back to room temperature. This process also requires that the sample have a clean surface, which is challenging because other atoms and molecules (like oxygen and water) can easily adsorb to the surface and modify the surface energy.

Surface energies obtained by this method are averaged values that lack the facet-specific resolution that is necessary for design, Ong said. “This is one of the areas where the ’virtual laboratory’ can create the most value—by allowing us to precisely control the models and conditions in a way that is extremely difficult to do in experiments.”

Also, the surface energy is not just a single number for each crystal because it depends on the crystal’s orientation. “A crystal is a regular arrangement of atoms. When you cut a crystal in different places and at different angles, you expose different facets with unique arrangements of atoms,” explained Ong, who teaches the course NANO106 – Crystallography of Materials at UC San Diego.

To carry out this ambitious project, Ong and his team developed highly sophisticated automated workflows to calculate surface energies from first principles. These workflows are built on the popular open-source Python Materials Genomics library and FireWorks workflow codes of the Materials Project, which were co-authored by Ong.

“The techniques for calculating surface energies have been known for decades. The major accomplishment is the codification of how to generate surface models and run these complex calculations in a robust and efficient manner,” Tran said. The surface model generation software code developed by the team has already been extended by others to study substrates and interfaces. Powerful supercomputers at the San Diego Supercomputer Center and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab were used for the calculations.

Ong’s team worked with researchers from the Berkeley Lab’s Materials Project to develop and construct Crystalium’s website. Co-founded and directed by Berkeley Lab scientist Kristin Persson, the Materials Project is a Google-like database of material properties calculated by supercomputers.

“The Materials Project was designed to be an open and accessible tool for scientists and engineers to accelerate materials innovation,” Persson said. “In five years, it has attracted more than 20,000 users working on everything from batteries to photovoltaics to thermoelectrics, and it’s extremely gratifying to see scientists like Ong providing lots of high quality computed data of high interest and making it freely available and easily accessible to the public.”

The researchers pointed out that their database is the most extensive collection of calculated surface energies for elemental crystalline solids to date. Compared to previous compilations, Crystalium contains surface energies for far more elements, including both metals and non-metals, and for more facets in each crystal. The elements that have been excluded from their calculations are gases and radioactive elements. Notably, Ong and his team have validated their calculated surface energies with those from experiments, and the values are in excellent agreement.

Moving forward, the team will work on expanding the scope of the database beyond single elements to multi-element compounds like alloys, which are made of two or more different metals, and binary oxides, which are made of oxygen and one other element. Efforts are also underway to study the effect of common adsorbates, such as hydrogen, on surface energies, which is key to understanding the stability of surfaces in aqueous media.

“As we continue to build this database, we hope that the research community will see it as a useful resource for the rational design of target surface or interfacial properties,” said Ong,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Surface energies of elemental crystals by Richard Tran, Zihan Xu, Balachandran Radhakrishnan, Donald Winston, Wenhao Sun, Kristin A. Persson, & Shyue Ping Ong. Scientific Data 3, Article number: 160080 (2016) doi:10.1038/sdata.2016.80 Published online: 13 September 2016

This paper is open access.

Here, too, is a link to Crystalium.