The best part of this story is that they’re using biochar from rice hulls to create the nanocomposite catalyst. A July 19, 2019 news item on ScienceDaily reveals a few details about the research without discussing the rice hulls,

The research team of Dr. Jae-woo Choi and Dr. Kyung-won Jung of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology’s (KIST, president: Byung-gwon Lee) Water Cycle Research Center announced that it has developed a wastewater treatment process that uses a common agricultural byproduct to effectively remove pollutants and environmental hormones, which are known to be endocrine disruptors.

A July 19, 2019 Korea National Research Council of Science & Technology news release on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

The sewage and wastewater that are inevitably produced at any industrial worksite often contain large quantities of pollutants and environmental hormones (endocrine disruptors). Because environmental hormones do not break down easily, they can have a significant negative effect on not only the environment but also the human body. To prevent this, a means of removing environmental hormones is required.

The performance of the catalyst that is currently being used to process sewage and wastewater drops significantly with time. Because high efficiency is difficult to achieve given the conditions, the biggest disadvantage of the existing process is the high cost involved. Furthermore, the research done thus far has mostly focused on the development of single-substance catalysts and the enhancement of their performance. Little research has been done on the development of eco-friendly nanocomposite catalysts that are capable of removing environmental hormones from sewage and wastewater.

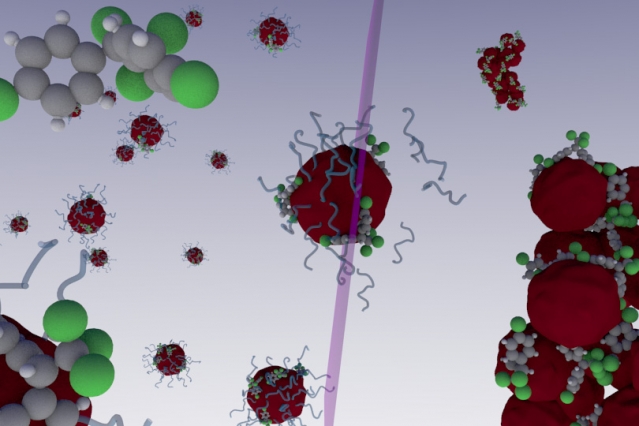

The KIST research team, led by Dr. Jae-woo Choi and Dr. Kyung-won Jung, utilized biochar,** which is eco-friendly and made from agricultural byproducts, to develop a wastewater treatment process that effectively removes pollutants and environmental hormones. The team used rice hulls [emphasis mine] which are discarded during rice harvesting, to create a biochar that is both eco-friendly and economical. The surface of the biochar was coated with nano-sized manganese dioxide to create a nanocomposite. The high efficiency and low cost of the biochar-nanocomposite catalyst is based on the combination of the advantages of the biochar and manganese dioxide.

**Biochar: a term that collectively refers to substances that can be created through the thermal decomposition of diverse types of biomass or wood under oxygen-limited condition

The KIST team used the hydrothermal method, which is a type of mineral synthesis that uses high heat and pressure, when synthesizing the nanocomposite in order to create a catalyst that is highly active, easily replicable, and stable. It was confirmed that giving the catalyst a three-dimensional stratified structure resulted in the high effectiveness of the advanced oxidation process (AOP), due to the large surface area created.

When used under the same conditions in which the existing catalyst can remove only 80 percent of Bisphenol A (BPA), an environmental hormone, the catalyst developed by the KIST team removed over 95 percent in less than one hour. In particular, when combined with ultrasound (20kHz), it was confirmed that all traces of BPA were completely removed in less than 20 minutes. Even after many repeated tests, the BPA removal rate remained consistently at around 93 percent.

Dr. Kyung-won Jung of KIST’s Water Cycle Research Center said, “The catalyst developed through this study makes use of a common agricultural byproduct. Therefore, we expect that additional research on alternative substances will lead to the development of catalysts derived from various types of organic waste biomass.” Dr. Jae-woo Choi, also of KIST’s Water Cycle Research Center, said, “We have high hopes that future studies aimed at achieving process optimization and increasing removal rates will allow for the development an environmental hormone removal system that is both eco-friendly and low-cost.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ultrasound-assisted heterogeneous Fenton-like process for bisphenol A removal at neutral pH using hierarchically structured manganese dioxide/biochar nanocomposites as catalysts by Kyung-Won Jung, Seon Yong Lee, Young Jae Lee, Jae-Woo Choi. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry

Volume 57, October 2019, Pages 22-28 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.04.039 Available online 29 April 2019

This paper is behind a paywall.