I mentioned it on Twitter (http://twitter.com/frogheart) and now I’m going to highlight Andy Connelly’s delightful article on stained glass windows here. From the Guardian’s Science Desk blog posting of Oct. 29, 2010,

The history of stained glass dates back to the middle ages [emphasis mine] and is an often underestimated technical and artistic achievement.

Glass itself is one of the fruits of the art of fire. It is a fusion of the Earth’s rocks: a mixture of sand (silicon oxide), soda (sodium oxide) and lime (calcium oxide) melted at high temperatures. Glass is an enabling material used for more than just drinking vessels and windows. It also allows scientists to observe distant stars and the smallest biological cells, and colourful chemical reactions in test tubes.

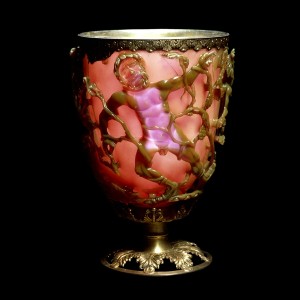

I’ve read a number of times that the deep reds in the stained glass windows in medieval cathedrals are due to gold nanoparticles. According to a 2007 article about the Lycurgus Cup by Ian Freestone, Nigel Meeks, Margaret Sax and Catherine Higgitt for the Gold Bulletin, Vol. 40:4, 2007, this is not the case. (I featured the Lycurgus Cup and ancient Roman nanotechnology in my Sept. 21, 2010 posting.) From the Freestone, et. al. article,

Although the red “stained” glass of medieval church windows is sometimes suggested to be gold ruby, the colourant has been found to be copper in all cases so far analysed. The production of gold ruby on anything like a routine basis does not appear to have taken place until the seventeenth century in Europe, a discovery often credited to Johann Kunckel, a German glassmaker and chemist. (p. 275)

One of these days I should do some more checking about nanoparticles and stained glass, in the meantime, Connelly notes that humans have had a longstanding contact with glass,

The earliest evidence of human interaction with glass was the discovery of flaked obsidian tools and arrow heads dating from more than 200,000 years ago. Obsidian is a volcanic glass formed when hot volcanic lava is rapidly cooled.

…

Sheets of glass both blown and cast have been used architecturally since Roman times. Writers as early as the fifth century mention coloured glass in windows. Around AD 1000 Europe became less war-like, and church building and stained glass production began to flourish. However, these churches were Romanesque in style with massive walls and pillars to bear their weight and so had only relatively small windows.

But by the 12th century the pointed arch and flying buttresses of the Gothic style were allowing builders to insert “walls of light”, giant windows that filled the church interior with the perfect light of God.

Connelly also covers the chemistry,

So what is a glass? Why can we see through it when other materials are opaque? Glasses exist in a poorly understood state somewhere between solids and liquids. [If I ever knew that interesting fact, I’ve long since forgotten it.] In general, when a liquid is cooled there is a temperature at which it will “freeze”, becoming a crystalline solid (eg. water into ice at 0C). Most solid inorganic materials are crystalline and are made up of many millions of crystals, each having an atomic structure which is highly ordered, with atomic units tessellating throughout. The shape of these units can be observed in the shape of single crystals (eg. hexagonal quartz crystals).

Glass is different: it is not crystalline but made up of a continuous network of atoms that are not ordered but irregular and liquid-like. This difference in atomic structure occurs because the liquid glass is cooled so quickly that the atoms do not have time to arrange themselves into regular, crystal-like patterns.

If cooled fast enough almost any liquid can form glass, even water. However, the rate of cooling must be very fast. Fortunately for us, liquids composed primarily of silicon oxide can be cooled slowly and still form a glass. They get gradually stiffer during cooling until they reach the “glass transition temperature” below which they are effectively solid.

This transparent silicate material is what we know as glass, and despite its liquid-like atomic structure it is to all intents and purposes solid, only flowing over billions of years – much too slowly to be noticed in the hundreds of years cathedral windows have been in place.

There’s a lot more to the article including a description of three different processes that result in what we (uninformed individuals) call stained glass. Connelly, a cookery writer and former researcher in glass science who’s training to be a science teacher, explains (in addition to the history and the chemistry) how the windows were constructed so that they convey stories and display figures with expressive features. Do go and read this article if the subject interests you at all.