As you might expect, the US Army course on nanotechnology stresses the importance of nanotechnology for the military, according to a June 16, 2016 news item on Nanowerk,

If there is one lesson to glean from Picatinny Arsenal’s new course in nanomaterials, it’s this: never underestimate the power of small.

Nanotechnology is the study of manipulating matter on an atomic, molecular, or supermolecular scale. The end result can be found in our everyday products, such as stained glass [This is a reference to the red glass found in churches from the Middle Ages. More about this later in the posting], sunscreen, cellphones, and pharmaceutical products.

Other examples are in U.S. Army items such as vehicle armor, Soldier uniforms, power sources, and weaponry. All living things also can be considered united forms of nanotechnology produced by the forces of nature.

“People tend to think that nanotechnology is all about these little robots roaming around, fixing the environment or repairing damage to your body, and for many reasons that’s just unrealistic,” said Rajen Patel, a senior engineer within the Energetics and Warheads Manufacturing Technology Division, or EWMTD.

The division is part of the U.S. Army Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center or ARDEC.

A June 15, 2016 ARDEC news release by Cassandra Mainiero, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

“For me, nanotechnology means getting materials to have these properties that you wouldn’t expect them to have.” [Patel]

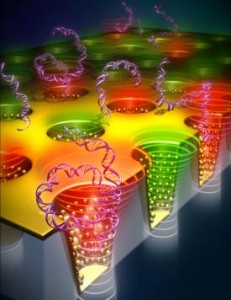

The subject can be separated into multiple types (nanomedicine, nanomachines, nanoelectronics, nanocomposites, nanophotonics and more), which can benefit areas, such as communications, medicine, environment remediation, and manufacturing.

Nanomaterials are defined as materials that have at least one dimension in the 1-100 nm range (there are 25,400,000 nanometers in one inch.) To provide some size perspective: comparing a nanometer to a meter is like comparing a soccer ball to the earth.

Picatinny’s nanomaterials class focuses on nanomaterials’ distinguishing qualities, such as their optical, electronic, thermal and mechanical properties–and teaches how manipulating them in a weapon can benefit the warfighter [soldier].

While you could learn similar information at a college course, Patel argues that Picatinny’s nanomaterial class is nothing like a university class.

This is because Picatinny’s nanomaterials class focuses on applied, rather than theoretical nanotechnology, using the arsenal as its main source of examples.

“We talk about things like what kind of properties you get, how to make materials, places you might expect to see nanotechnology within the Army,” explained Patel.

The class is taught at the Armament University. Each class lasts three days. The last one was held in February.

Each class includes approximately 25 students and provides an overview of nanotechnology, covering topics, such as its history, early pioneers in the field, and everyday items that rely on nanotechnology.

Additionally, the course covers how those same concepts apply at Picatinny (for electronics, sensors, energetics, robotics, insensitive munitions, and more) and the major difficulties with experimenting and manufacturing nanotechnology.

Moreover, the class involves guest talks from Picatinny engineers and scientists, such as Dan Kaplan, Christopher Haines, and Venkataraman Swaminathan as well as tours of Picatinny facilities like the Nanotechnology Center and the Explosives Research Laboratory.

It also includes lectures from guest speakers, such as Gordon Thomas from the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), who spoke about nanomaterials and diabetes research.

A CLASSROOM COINCIDENCE

Relatively new, the nanomaterials class launched in January 2015. It was pioneered by Patel after he attended an instructional course on teaching at the Armament University, where he met Erin Williams, a technical training analyst at the university.

“At the Armament University, we’re always trying to think of, ‘What new areas of interest should we offer to help our workforce? What forward reaching technologies are needed?’ One topic that came up was nanotechnology,” said Williams about how the nanomaterials class originated.

“I started to do research on the subject, how it might be geared toward Picatinny, and trying to think of ways to organize the class. Then, I enrolled in the instructional course on teaching, where I just so happen to be sitting across from Dr. Rajen Patel, who not only knew about nanotechnology, but taught a few seminars at NJIT, where he did his doctorate,” explained Williams. “I couldn’t believe the coincidence! So, I asked him if he would be interested in teaching a class and he said ‘Yes!'”

“After the first [nanomaterials] class, one of the students came up to me and said ‘This was the best course I’ve ever been to on this arsenal,'” added Williams. “…This is really how Picatinny shines as a team: when you meet people and utilize your knowledge to benefit the organization.”

The success of the first nanomaterials course encouraged Patel to expand his class into specialty fields, designing a two-day nanoenergetics class taught by himself and Victor Stepanov, a senior scientist at EWMTD.

Stepanov works with nano-organic energetics (RDX, HMX, CL-20) and inorganic materials (metals.) He is responsible for creating the first nanoorganic energetic known as nano-RDX. He is involved in research aimed at understanding the various properties of nanoenergetics including sensitivity, performance, and mechanical characteristics. He and Patel teach the nanoenergetics class that was first offered last fall and due to high demand is expected to be offered annually. The next one will be held in September.

“We always ask for everyone’s feedback. And, after our first class, everyone said ‘[Picatinny] is the home of the Army’s lethality–why did we not talk about nanoenergetics?’ So, in response to the student’s feedback, we implemented that nanoenergetics course,” said Patel. “Besides, in the long run, you’ll probably replace most energetics with nano-energetics, as they have far too many advantages.”

TECHNOLOGY EVOLUTION

Since all living things are a form of nanotechnology manipulated by the forces of nature, the history of nanotechnology dates back to the emergence of life. However, a more concrete example can be traced back to ancient times, when nanomaterials were manipulated to create gold and silver art such as Lycurgus Cup, a 4th century Roman glass [I’ve added more about the Lycurgus Cup later in this post].

According to Stepanov, ARDEC’s interest in nanotechnology gained significant momentum approximately 20 years ago. The initiative at ARDEC was directly tied to the emergence of advanced technologies needed for production and characterization of nanomaterials, and was concurrent with adoption of nanotechnologies in other fields such as pharmaceuticals.

In 2010, an article in The Picatinny Voice titled “Tiny particles, big impact: Nanotechnology to help warfighters” discussed Picatinny’s ongoing research on nanopowders.

It noted that Picatinny’s Nanotechnology Lab is the largest facility in North America to produce nanopowders and nanomaterials, which are used to create nanoexplosives.

It also mentioned how using nanomaterials helped to develop lightweight composites as an alternative to traditional steel.

The more recent heightened study is due to the evolution of technology, which has allowed engineers and scientists to be more productive and made nanotechnology more ubiquitous throughout the military.

“Not too long ago making milligram quantities of nanoexplosives was challenging. Now, we have technologies that allow us make pounds of nanoexplosives per hour at low cost,” said Stepanov.

Pilot scale production of nanoexplosives is currently being performed at ARDEC, lead by Ashok Surapaneni of the Explosives Development Branch.

The broad interest in developing nanoenergetics such as nano-RDX and nano-HMX is their remarkably low initiation sensitivity.

These materials can thus be crucial in the development of safer next generation munitions that are much less vulnerable to accidental initiation.

SMALL CHANGES, BIG RESULTS

As a result, working with nanotechnology can have various payoffs, such as enhancing the performance of military products, said Patel. For instance, by manipulating nanomaterials, an engineer could make a weapon stronger, lighter, or increase its reactivity or durability.

“Generally, if you make something more safe, you make it less powerful,” said Stepanov. “But, with nanomaterials, you can make a product more safe and, in many cases, more powerful.”

There are two basic approaches to studying nanomaterials: bottom-up (building a large object atom by atom) and top-down (deconstructing a larger material.) Both approaches have been successfully employed in the development of nanoenergetics at ARDEC.

One of the challenges with manufacturing nonmaterials can be coping with shockwaves.

A shockwave initiates an explosive as it travels through a weapon’s main fill or the booster. When a shockwave travels through an energetic charge, it can hit small regions of defects, or voids, which heat up quickly and build pressure until the explosive reaches detonation. By using nanoenergetics, one could adjust the size and quantity of the defects and voids, so that the pressure isn’t as strong and ultimately prevent accidental detonation.

Nanomaterials also are difficult to process because they tend to agglomerate (stick together) and are also prone to Ostwald Ripening, or spontaneous growth of the crystals, which is especially pronounced at the nano-scale. This effect is commonly observed with ice cream, where ice can re-crystallize, resulting in a gritty texture.

“It’s a major production challenge because if you want to process nanomaterials–if you want to coat it with some polymer for explosives–any kind of medium that can dissolve these types of materials can promote ripening and you can end up with a product which no longer has the nanomaterial that you began with,” explained Stepanov.

However, nanotechnology research continues to grow at Picatinny as the research advances in the U.S. Army.

This ongoing development and future applicability encourages Patel and Stepanov to teach the nanomaterials and nanoenergetics course at Picatinny.

“I’m interested in making things better for the warfighter,” said Patel. “Nano-materials give you so many opportunities to do so. Also, as a scientist, it’s just a fascinating realm because you always get these little interesting surprises.

“You can know all the material science and equations, but then you get in the nano-world, and there’s something like a wrinkle–something you wouldn’t expect,” Patel added.

“It satisfies three deep needs: getting the warfighter technology, producing something of value, and it’s fun. You always see something new.”

Medieval church windows and the Lycurgus Cup

The shade of red in medieval church window glass is said to have been achieved by the use of gold nanoparticles. There is a source which claims the colour is due to copper rather than gold. I have not had to time to pursue the controversy such as it is but do have November 1, 2010 posting about stained glass and medieval churches which may prove of interest.

As for the Lycurgus Cup, it’s from the 4th century (CE or AD) and is an outstanding example of Roman art and craft. The glass in the cup is dichroic (it looks green or red depending on how the light catches it). The effect was achieved with the presence of gold and silver nanoparticles in the glass. I have a more extensive description and pictures in a Sept. 21, 2010 posting.

Final note

There is an army initiative involving an educational institution, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The initiative is the MIT Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies.