I have two bits today and both concern science and Twitter.

Twitter science research

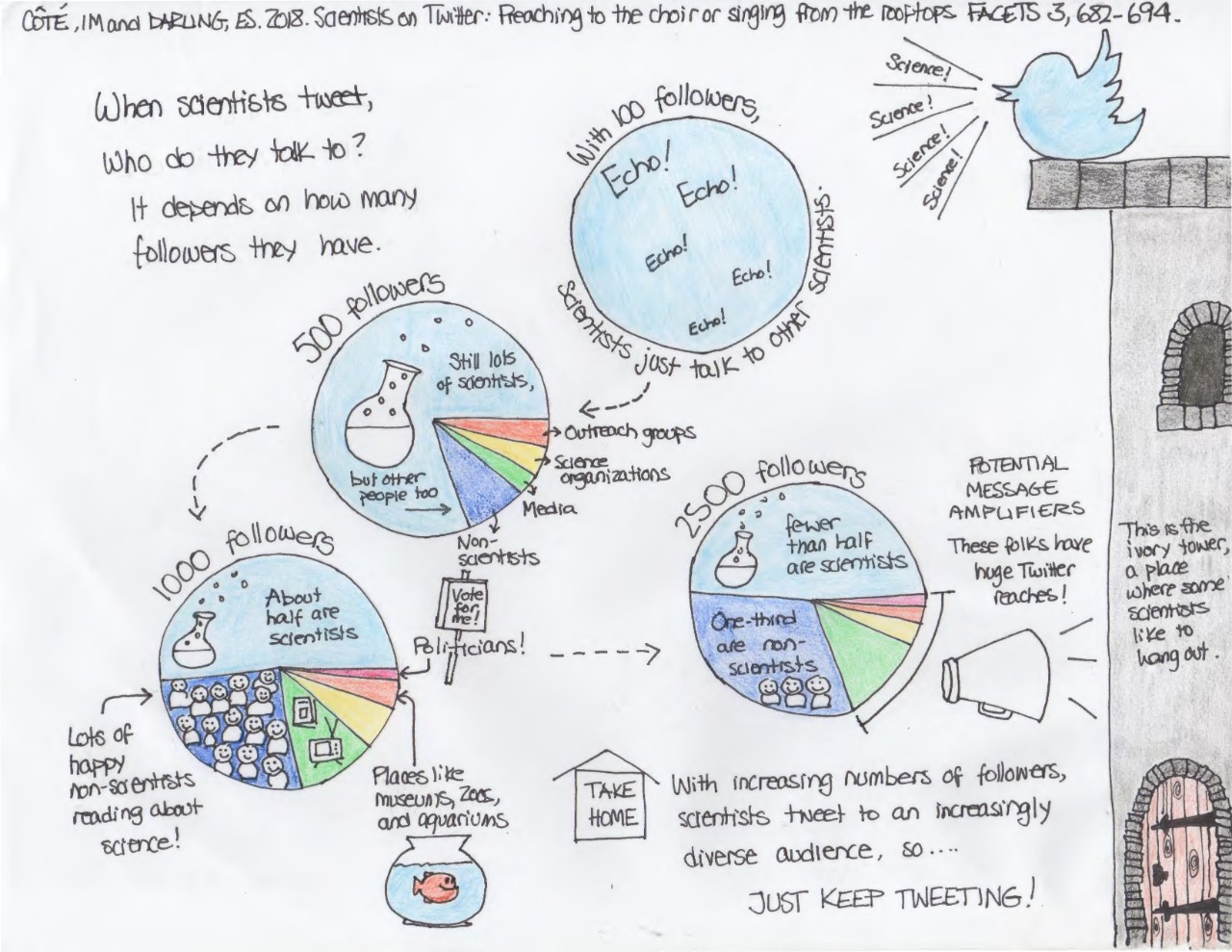

A doodle by Isabelle Côté to illustrate her recent study on the effectiveness of scientists using Twitter to share their research with the public. Credit: Isabelle Côté

I was quite curious about this research on scientists and their Twitter audiences coming from Simon Fraser University (SFU; Vancouver, Canada). From a July 11, 2018 SFU news release (also on EurekAlert),

Isabelle Côté is an SFU professor of marine ecology and conservation and an active science communicator whose prime social media platform is Twitter.

Côté, who has cultivated more than 5,800 followers since she began tweeting in 2012, recently became curious about who her followers are.

“I wanted to know if my followers are mainly scientists or non-scientists – in other words was I preaching to the choir or singing from the rooftops?” she says.

Côté and collaborator Emily Darling set out to find the answer by analyzing the active Twitter accounts of more than 100 ecology and evolutionary biology faculty members at 85 institutions across 11 countries.

Their methodology included categorizing followers as either “inreach” if they were academics, scientists and conservation agencies and donors; or “outreach” if they were science educators, journalists, the general public, politicians and government agencies.

Côté found that scientists with fewer than 1,000 followers primarily reach other scientists. However, scientists with more than 1,000 followers have more types of followers, including those in the “outreach” category.

Twitter and other forms of social media provide scientists with a potential way to share their research with the general public and, importantly, decision- and policy-makers. Côté says public pressure can be a pathway to drive change at a higher level. However, she notes that while social media is an asset, it is “not likely an effective replacement for the more direct science-to-policy outreach that many scientists are now engaging in, such as testifying in front of special governmental committees, directly contacting decision-makers, etc.”

Further, even with greater diversity and reach of followers, the authors concede there are still no guarantees that Twitter messages will be read or understood. Côté cites evidence that people selectively read what fits with their perception of the world, that changing followers’ minds about deeply held beliefs is challenging.

“While Twitter is emerging as a medium of choice for scientists, studies have shown that less than 40 per cent of academic scientists use the platform,” says Côté.

“There’s clearly a lot of room for scientists to build a social media presence and increase their scientific outreach. Our results provide scientists with clear evidence that social media can be used as a first step to disseminate scientific messages well beyond the ivory tower.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper (my thoughts on the matter are after),

Scientists on Twitter: Preaching to the choir or singing from the rooftops? by Isabelle M. Côté and Emily S. Darling. Facets DOI: https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2018-0002 Published Online 28 June 2018

This paper is in an open access journal.

Thoughts on the research

Neither of the researchers, Côté and Darling, appears to have any social science training; so where I’d ordinarily laud the researchers for their good work, I have to include extra kudos for taking on a type of research outside their usual domain of expertise.

If this sort of thing interests you and you have the time, I definitely recommend reading the paper (from the paper‘s introduction), Note: Links have been removed)

Communication has always been an integral part of the scientific endeavour. In Victorian times, for example, prominent scientists such as Thomas H. Huxley and Louis Agassiz delivered public lectures that were printed, often verbatim, in newspapers and magazines (Weigold 2001), and Charles Darwin wrote his seminal book “On the origin of species” for a popular, non-specialist audience (Desmond and Moore 1991). In modern times, the pace of science communication has become immensely faster, information is conveyed in smaller units, and the modes of delivery are far more numerous. These three trends have culminated in the use of social media by scientists to share their research in accessible and relevant ways to potential audiences beyond their peers. The emphasis on accessibility and relevance aligns with calls for scientists to abandon jargon and to frame and share their science, especially in a “post-truth” world that can emphasize emotion over factual information (Nisbet and Mooney 2007; Bubela et al. 2009; Wilcox 2012; Lubchenco 2017).

The microblogging platform Twitter is emerging as a medium of choice for scientists (Collins et al. 2016), although it is still used by a minority (<40%) of academic faculty (Bart 2009; Noorden 2014). Twitter allows users to post short messages (originally up to 140 characters, increased to 280 characters since November 2017) that can be read by any other user. Users can elect to follow other users whose posts they are interested in, in which case they automatically see their followees’ tweets; conversely, users can be followed by other users, in which case their tweets can be seen by their followers. No permission is needed to follow a user, and reciprocation of following is not mandatory. Tweets can be categorized (with hashtags), repeated (retweeted), and shared via other social media platforms, which can exponentially amplify their spread and can offer links to websites, blogs, or scientific papers (Shiffman 2012).

There are scientific advantages to using digital communication technologies such as Twitter. Scientific users describe it as a means to stay abreast of new scientific literature, grant opportunities, and science policy, to promote their own published papers and exchange ideas, and to participate in conferences they cannot attend in person as “virtual delegates” (Bonetta 2009; Bik and Goldstein 2013; Parsons et al. 2014; Bombaci et al. 2016). Twitter can play a role in most parts of the life cycle of a scientific publication, from making connections with potential collaborators, to collecting data or finding data sources, to dissemination of the finished product (Darling et al. 2013; Choo et al. 2015). There are also some quantifiable benefits for scientists using social media. For example, papers that are tweeted about more often also accumulate more citations (Eysenbach 2011; Thelwall et al. 2013; Peoples et al. 2016), and the volume of tweets in the first week following publication correlates with the likelihood of a paper becoming highly cited (Eysenbach 2011), although such relationships are not always present (e.g., Haustein et al. 2014).

In addition to any academic benefits, scientists might adopt social media, and Twitter in particular, because of the potential to increase the reach of scientific messages and direct engagement with non-scientific audiences (Choo et al. 2015). This potential comes from the fact that Twitter leverages the power of weak ties, defined as low-investment social interactions that are not based on personal relationships (Granovetter 1973). On Twitter, follower–followee relationships are weak: users generally do not personally know the people they follow or the people who follow them, as their interactions are based mainly on message content. Nevertheless, by retweeting and sharing messages, weak ties can act as bridges across social, geographic, or cultural groups and contribute to a wide and rapid spread of information (Zhao et al. 2010; Ugander et al. 2012). The extent to which the messages of tweeting scientists benefit from the power of weak ties is unknown. Does Twitter provide a platform that allows scientists to simply promote their findings to other scientists within the ivory tower (i.e., “inreach”), or are tweeting scientists truly exploiting social media to potentially reach new audiences (“outreach”) (Bik et al. 2015; McClain and Neeley 2015; Fig. 1)?

Fig. 1. Conceptual depiction of inreach and outreach for Twitter communication by academic faculty. Left: If Twitter functions as an inreach tool, tweeting scientists might primarily reach only other scientists and perhaps, over time (arrow), some applied conservation and management science organizations. Right: If Twitter functions as an outreach tool, tweeting scientists might first reach other scientists, but over time (arrow) they will eventually attract members of the media, members of the public who are not scientists, and decision-makers (not necessarily in that order) as followers.

I’m glad to see this work but it’s use of language is not as precise in some places as it could be. They use the term ‘scientists’ throughout but their sample is made up of scientists identified as ecology and/or evolutionary biology (EEMB) researchers, as they briefly note in their Abstract and in the Methods section. With the constant use of the generic term, scientist, throughout most of the paper and taken in tandem with its use in the title, it’s easy to forget that this was a sample of a very specific population..

That the researchers’ sample of EEMB scientists is made up of those working at universities (academic scientists) is clear and it presents an interesting problem. How much does it matter that these are academic scientists? Both in regard to the research itself and with regard to perceptions about scientists. A sentence stating the question is beyond the scope of their research might have been a good idea.

Impressively, Darling and Côté have reached past the English language community to include other language groups, “We considered as many non-English Twitter profiles as possible by including common translations of languages we were familiar with (i.e., French and Spanish: biologista, professeur, profesora, etc.) in our search strings; …”

I cannot emphasize how rare it is to see this attempt to reach out beyond the English language community. Yes!

Getting back to my concern about language, I would have used ‘suspect’ rather than ‘assume’ in this sentence from the paper’s Discussion, “We assume [emphasis mine] that the patterns we have uncovered for a sample of ecologists and evolutionary biologists in faculty positions can apply broadly across other academic disciplines.” I agree it’s quite likely but it’s an hypothesis/supposition and needs to be tested. For example, will this hold true if you examine social scientists (such as economists, linguists, political scientists, psychologists, …) or physicists or mathematicians or …?

Is this evidence of unconscious bias regarding wheat the researchers term as ‘non-scientists’? From the paper’s Discussion (Note: Links have been removed),

Of course, high numbers, diversity, and reach of followers offer no guarantee that messages will be read or understood. There is evidence that people selectively read what fits with their perception of the world (e.g., Sears and Freedman 1967; McPherson et al. 2001; Sunstein 2001; Himelboim et al. 2013). Thus, non-scientists [emphases mine] who follow scientists on Twitter might already be positively inclined to consume scientific information. If this is true, then one could argue that Twitter therefore remains an echo chamber, but it is a much larger one than the usual readership of scientific publications. Moreover, it is difficult to gauge the level of understanding of scientific tweets. The brevity and fragmented nature of science tweets can lead to shallow processing and comprehension of the message (Jiang et al. 2016). One metric of the influence of tweets is the extent to which they are shared (i.e., retweeted). Twitter users retweet posts when they find them interesting (hence the posts were at least read, if not understood) and when they deem the source credible (Metaxas et al. 2015). To our knowledge, there are no data on how often tweets by scientists are reposted by different types of followers. Such information would provide further evidence for an outreach function of Twitter in science communication.

Yes, it’s true that high numbers, etc. do not guarantee your messages will be read or understood and that people do selectively choose what fits their perception of the world. However, that applies equally to scientists and non-scientists despite what the authors appear to be claiming. Also, their use of the term non-scientist is not clear to me. Is this a synonym for ‘general public’ or is it being applied to anyone who may not have an educational background in science but is designated in another category such as policy makers, science communicators, etc. in the research paper?

In any event, ‘policy makers’ absorb a great deal of the researchers’ attention, from the paper’s Discussion (Note: Links have been removed),

Under most theories of change that describe how science ultimately affects evidence-based policies, decision-makers are a crucial group that should be engaged by scientists (Smith et al. 2013). Policy changes can be effected either through direct application of research to policy or, more often, via pressure from public awareness, which can drive or be driven by research (Baron 2010; Phillis et al. 2013). Either pathway requires active engagement by scientists with society (Lubchenco 2017). It is arguably easier than ever for scientists to have access to decision- and policy-makers, as officials at all levels of government are increasingly using social media to connect with the public (e.g., Grant et al. 2010; Kapp et al. 2015). However, we found that decision-makers accounted for only ∼0.3% (n = 191 out of 64 666) of the followers of academic scientists (see also Bombaci et al. 2016 in relation to the audiences of conference tweeting). Moreover, decision-makers begin to follow scientists in greater numbers only once the latter have reached a certain level of “popularity” (i.e., ∼2200 followers; Table 2). The general concern about whether scientific tweets are actually read by followers applies even more strongly to decision-makers, as they are known to use Twitter largely as a broadcasting tool rather than for dialogue (Grant et al. 2010). Thus, social media is not likely an effective replacement for more direct science-to-policy outreach that many scientists are now engaging in, such as testifying in front of special governmental committees, directly contacting decision-makers, etc. However, by actively engaging a large Twitter following of non-scientists, scientists increase the odds of being followed by a decision-maker who might see their messages, as well as the odds of being identified as a potential expert for further contributions.

It may due to the types of materials I tend to stumble across but science outreach has usually been presented as largely an educational effort with the long term goal of assuring the public will continue to support science funding. This passage in the research paper suggests more immediate political and career interests.

Should scientists be on Twitter?

This paper might discourage someone whose primary goal is to reach policy makers via this social media platform but the researchers seem to feel there is value in reaching out to a larger audience. While I’m not comfortable with how the researchers have generalized their results to the entire population of scientists, those results are intriguing..

This next bit features a scientist who as it turns out could be described as an EEMB (evolutionary biology and/or ecology) researcher.

How to tweet science

Stephen Heard wrote a July 31, 2018 posting on his Scientist Sees Squirrel blog about his Twitter feed,

At the 2018 conference of the Canadian Society for Ecology and Evolution, I was part of a lunchtime workshop, “The How and Why of Tweeting Science” – along with 5 friends. Here I’ll share my slides and commentary. I hope the other presenters will do the same, and I’ll link to them here as they become available.

I’ve been active on Twitter for about 4 years, but I’m very far from an expert, so my contribution to #CSEETweetShop was more to raise questions than to answer them. What does it mean to “tweet to the science community”? Here I’ll share some thoughts about Twitter audience, content, and voice. These are, of course, my own (roughly formed) opinions, not some kind of wisdom on stone tablets, so take them with the requisite grain of salt!

Audience

Just as we do with blogging, we can draw a distinction between two audiences we might intend to reach via Twitter. We might use Twitter for outreach, to talk to the general public – we could call this “science-communication tweeting”. Or we could use Twitter for “inreach”, to talk to other scientists – which is what I’d call “science-community tweeting”. But: for a couple of reasons, this distinction is not as clear as you might thing. Or at least, your intent to reach one audience or the other may not match the outcome.

There are some data on the topic of scientists’ Twitter audiences. The data in the slide above come from a recent paper by Isabelle Coté and Emily Darling. They’re for a sample of 110 faculty members in ecology and evolution, for whom audiences are broken down by their relationship (if any) to science. The key result: most ecology and evolution faculty on Twitter have audiences dominated by other scientists (light blue), with the general public (dark blue) a significant but more modest chunk. There’s variation, some of which may well relate to the tweeters’ intended audiences – but we can draw two fairly clear conclusions:

- Nearly all of us tweet mostly to the science community; but

- Almost none of us tweets only to the science community (or for that matter only to the general public).

The same paper analyzes follower composition as a function of audience size, and these data suggest that one’s audience is likely to change it builds. Notice how the dark-blue “general public” line lags behind, then catches, the light-blue “other scientists” line*. Earlier in your Twitter career, it’s likely that your audience will be even more strongly dominated by the science community – whether or not that’s what you intend.

In short: you probably can’t pick the audience you’re talking to; but you can pick the audience you’re talking for. Given that, how might you use Twitter to talk for the science community?

…

I particularly like his constant questions about audience. He discusses other issues, such as content, but he always returns to the audience. Having worked in communication(s) and marketing, I have to applaud his focus on the audience. I can’t tell you how many times, we’d answer the question as to whom our audience was and we’d never revisit it. (mea culpa) Heard’s insistence on constantly checking in and questioning your assumptions is excellent.

Seeing Coté’s and Darling’s paper cited in his presentation, gives some idea of how closely he follows the thinking about science outreach in his field.

Both Coté’s and Darling’s academic paper and Heard’s posting make for accessible reading while offering valuable information.