AI artists first hit my radar in August 2018 when Christie’s Auction House advertised an art auction of a ‘painting’ by an algorithm (artificial intelligence). There’s more in my August 31, 2018 posting but, briefly, a French art collective, Obvious, submitted a painting, “Portrait of Edmond de Belamy,” that was created by an artificial intelligence agent to be sold for an estimated to $7000 – $10,000. They weren’t even close. According to Ian Bogost’s March 6, 2019 article for The Atlantic, the painting sold for $432,500 In October 2018.

It has also, Bogost notes in his article, occasioned an art show (Note: Links have been removed),

… part of “Faceless Portraits Transcending Time,” an exhibition of prints recently shown [Februay 13 – March 5, 2019] at the HG Contemporary gallery in Chelsea, the epicenter of New York’s contemporary-art world. All of them were created by a computer.

The catalog calls the show a “collaboration between an artificial intelligence named AICAN and its creator, Dr. Ahmed Elgammal,” a move meant to spotlight, and anthropomorphize, the machine-learning algorithm that did most of the work. According to HG Contemporary, it’s the first solo gallery exhibit devoted to an AI artist.

If they hadn’t found each other in the New York art scene, the players involved could have met on a Spike Jonze film set: a computer scientist commanding five-figure print sales from software that generates inkjet-printed images; a former hotel-chain financial analyst turned Chelsea techno-gallerist with apparent ties to fine-arts nobility; a venture capitalist with two doctoral degrees in biomedical informatics; and an art consultant who put the whole thing together, A-Team–style, after a chance encounter at a blockchain conference. Together, they hope to reinvent visual art, or at least to cash in on machine-learning hype along the way.

The show in New York City, “Faceless Portraits …,” exhibited work by an artificially intelligent artist-agent (I’m creating a new term to suit my purposes) that’s different than the one used by Obvious to create “Portrait of Edmond de Belamy,” As noted earlier, it sold for a lot of money (Note: Links have been removed),

Bystanders in and out of the art world were shocked. The print had never been shown in galleries or exhibitions before coming to market at auction, a channel usually reserved for established work. The winning bid was made anonymously by telephone, raising some eyebrows; art auctions can invite price manipulation. It was created by a computer program that generates new images based on patterns in a body of existing work, whose features the AI “learns.” What’s more, the artists who trained and generated the work, the French collective Obvious, hadn’t even written the algorithm or the training set. They just downloaded them, made some tweaks, and sent the results to market.

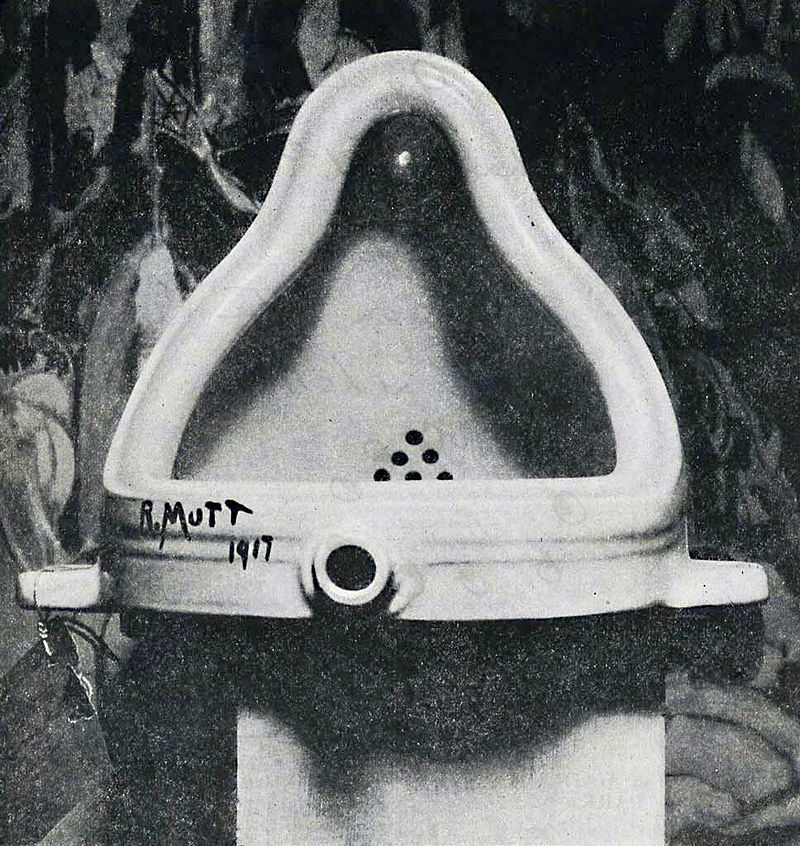

“We are the people who decided to do this,” the Obvious member Pierre Fautrel said in response to the criticism, “who decided to print it on canvas, sign it as a mathematical formula, put it in a gold frame.” A century after Marcel Duchamp made a urinal into art [emphasis mine] by putting it in a gallery, not much has changed, with or without computers. As Andy Warhol famously said, “Art is what you can get away with.”

A bit of a segue here, there is a controversy as to whether or not that ‘urinal art’, also known as, The Fountain, should be attributed to Duchamp as noted in my January 23, 2019 posting titled ‘Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Marcel Duchamp, and the Fountain’.

Getting back to the main action, Bogost goes on to describe the technologies underlying the two different AI artist-agents (Note: Links have been removed),

… Using a computer is hardly enough anymore; today’s machines offer all kinds of ways to generate images that can be output, framed, displayed, and sold—from digital photography to artificial intelligence. Recently, the fashionable choice has become generative adversarial networks, or GANs, the technology that created Portrait of Edmond de Belamy. Like other machine-learning methods, GANs use a sample set—in this case, art, or at least images of it—to deduce patterns, and then they use that knowledge to create new pieces. A typical Renaissance portrait, for example, might be composed as a bust or three-quarter view of a subject. The computer may have no idea what a bust is, but if it sees enough of them, it might learn the pattern and try to replicate it in an image.

GANs use two neural nets (a way of processing information modeled after the human brain) to produce images: a “generator” and a “discerner.” The generator produces new outputs—images, in the case of visual art—and the discerner tests them against the training set to make sure they comply with whatever patterns the computer has gleaned from that data. The quality or usefulness of the results depends largely on having a well-trained system, which is difficult.

That’s why folks in the know were upset by the Edmond de Belamy auction. The image was created by an algorithm the artists didn’t write, trained on an “Old Masters” image set they also didn’t create. The art world is no stranger to trend and bluster driving attention, but the brave new world of AI painting appeared to be just more found art, the machine-learning equivalent of a urinal on a plinth.

Ahmed Elgammal thinks AI art can be much more than that. A Rutgers University professor of computer science, Elgammal runs an art-and-artificial-intelligence lab, where he and his colleagues develop technologies that try to understand and generate new “art” (the scare quotes are Elgammal’s) with AI—not just credible copies of existing work, like GANs do. “That’s not art, that’s just repainting,” Elgammal says of GAN-made images. “It’s what a bad artist would do.”

Elgammal calls his approach a “creative adversarial network,” or CAN. It swaps a GAN’s discerner—the part that ensures similarity—for one that introduces novelty instead. The system amounts to a theory of how art evolves: through small alterations to a known style that produce a new one. That’s a convenient take, given that any machine-learning technique has to base its work on a specific training set.

The results are striking and strange, although calling them a new artistic style might be a stretch. They’re more like credible takes on visual abstraction. The images in the show, which were produced based on training sets of Renaissance portraits and skulls, are more figurative, and fairly disturbing. Their gallery placards name them dukes, earls, queens, and the like, although they depict no actual people—instead, human-like figures, their features smeared and contorted yet still legible as portraiture. Faceless Portrait of a Merchant, for example, depicts a torso that might also read as the front legs and rear haunches of a hound. Atop it, a fleshy orb comes across as a head. The whole scene is rippled by the machine-learning algorithm, in the way of so many computer-generated artworks.

Bogost consults an expert on portraiture for a discussion about the particularities of portraiture and the shortcomings one might expect of an AI artist-agent (Note: A link has been removed),

“You can’t really pick a form of painting that’s more charged with cultural meaning than portraiture,” John Sharp, an art historian trained in 15th-century Italian painting and the director of the M.F.A. program in design and technology at Parsons School of Design, told me. The portrait isn’t just a style, it’s also a host for symbolism. “For example, men might be shown with an open book to show how they are in dialogue with that material; or a writing implement, to suggest authority; or a weapon, to evince power.” Take Portrait of a Youth Holding an Arrow, an early-16th-century Boltraffio portrait that helped train the AICAN database for the show. The painting depicts a young man, believed to be the Bolognese poet Girolamo Casio, holding an arrow at an angle in his fingers and across his chest. It doubles as both weapon and quill, a potent symbol of poetry and aristocracy alike. Along with the arrow, the laurels in Casio’s hair are emblems of Apollo, the god of both poetry and archery.

A neural net couldn’t infer anything about the particular symbolic trappings of the Renaissance or antiquity—unless it was taught to, and that wouldn’t happen just by showing it lots of portraits. For Sharp and other critics of computer-generated art, the result betrays an unforgivable ignorance about the supposed influence of the source material.

But for the purposes of the show, the appeal to the Renaissance might be mostly a foil, a way to yoke a hip, new technology to traditional painting in order to imbue it with the gravity of history: not only a Chelsea gallery show, but also an homage to the portraiture found at the Met. To reinforce a connection to the cradle of European art, some of the images are presented in elaborate frames, a decision the gallerist, Philippe Hoerle-Guggenheim (yes, that Guggenheim; he says the relation is “distant”) [the Guggenheim is strongly associated with the visual arts by way the two Guggeheim museums, one in New York City and the other in Bilbao, Portugal], told me he insisted upon. Meanwhile, the technical method makes its way onto the gallery placards in an official-sounding way—“Creative Adversarial Network print.” But both sets of inspirations, machine-learning and Renaissance portraiture, get limited billing and zero explanation at the show. That was deliberate, Hoerle-Guggenheim said. He’s betting that the simple existence of a visually arresting AI painting will be enough to draw interest—and buyers. It would turn out to be a good bet.

…

The art market is just that: a market. Some of the most renowned names in art today, from Damien Hirst to Banksy, trade in the trade of art as much as—and perhaps even more than—in the production of images, objects, and aesthetics. No artist today can avoid entering that fray, Elgammal included. “Is he an artist?” Hoerle-Guggenheim asked himself of the computer scientist. “Now that he’s in this context, he must be.” But is that enough? In Sharp’s estimation, “Faceless Portraits Transcending Time” is a tech demo more than a deliberate oeuvre, even compared to the machine-learning-driven work of his design-and-technology M.F.A. students, who self-identify as artists first.

Judged as Banksy or Hirst might be, Elgammal’s most art-worthy work might be the Artrendex start-up itself, not the pigment-print portraits that its technology has output. Elgammal doesn’t treat his commercial venture like a secret, but he also doesn’t surface it as a beneficiary of his supposedly earnest solo gallery show. He’s argued that AI-made images constitute a kind of conceptual art, but conceptualists tend to privilege process over product or to make the process as visible as the product.

Hoerle-Guggenheim worked as a financial analyst for Hyatt before getting into the art business via some kind of consulting deal (he responded cryptically when I pressed him for details). …

This is a fascinating article and I have one last excerpt, which poses this question, is an AI artist-agent a collaborator or a medium? There ‘s also speculation about how AI artist-agents might impact the business of art (Note: Links have been removed),

… it’s odd to list AICAN as a collaborator—painters credit pigment as a medium, not as a partner. Even the most committed digital artists don’t present the tools of their own inventions that way; when they do, it’s only after years, or even decades, of ongoing use and refinement.

But Elgammal insists that the move is justified because the machine produces unexpected results. “A camera is a tool—a mechanical device—but it’s not creative,” he said. “Using a tool is an unfair term for AICAN. It’s the first time in history that a tool has had some kind of creativity, that it can surprise you.” Casey Reas, a digital artist who co-designed the popular visual-arts-oriented coding platform Processing, which he uses to create some of his fine art, isn’t convinced. “The artist should claim responsibility over the work rather than to cede that agency to the tool or the system they create,” he told me.

Elgammal’s financial interest in AICAN might explain his insistence on foregrounding its role. Unlike a specialized print-making technique or even the Processing coding environment, AICAN isn’t just a device that Elgammal created. It’s also a commercial enterprise.

Elgammal has already spun off a company, Artrendex, that provides “artificial-intelligence innovations for the art market.” One of them offers provenance authentication for artworks; another can suggest works a viewer or collector might appreciate based on an existing collection; another, a system for cataloging images by visual properties and not just by metadata, has been licensed by the Barnes Foundation to drive its collection-browsing website.

The company’s plans are more ambitious than recommendations and fancy online catalogs. When presenting on a panel about the uses of blockchain for managing art sales and provenance, Elgammal caught the attention of Jessica Davidson, an art consultant who advises artists and galleries in building collections and exhibits. Davidson had been looking for business-development partnerships, and she became intrigued by AICAN as a marketable product. “I was interested in how we can harness it in a compelling way,” she says.

…

The art market is just that: a market. Some of the most renowned names in art today, from Damien Hirst to Banksy, trade in the trade of art as much as—and perhaps even more than—in the production of images, objects, and aesthetics. No artist today can avoid entering that fray, Elgammal included. “Is he an artist?” Hoerle-Guggenheim asked himself of the computer scientist. “Now that he’s in this context, he must be.” But is that enough? In Sharp’s estimation, “Faceless Portraits Transcending Time” is a tech demo more than a deliberate oeuvre, even compared to the machine-learning-driven work of his design-and-technology M.F.A. students, who self-identify as artists first.

Judged as Banksy or Hirst might be, Elgammal’s most art-worthy work might be the Artrendex start-up itself, not the pigment-print portraits that its technology has output. Elgammal doesn’t treat his commercial venture like a secret, but he also doesn’t surface it as a beneficiary of his supposedly earnest solo gallery show. He’s argued that AI-made images constitute a kind of conceptual art, but conceptualists tend to privilege process over product or to make the process as visible as the product.

Hoerle-Guggenheim worked as a financial analyst[emphasis mine] for Hyatt before getting into the art business via some kind of consulting deal (he responded cryptically when I pressed him for details). …

If you have the time, I recommend reading Bogost’s March 6, 2019 article for The Atlantic in its entirety/ these excerpts don’t do it enough justice.

Portraiture: what does it mean these days?

After reading the article I have a few questions. What exactly do Bogost and the arty types in the article mean by the word ‘portrait’? “Portrait of Edmond de Belamy” is an image of someone who doesn’t and never has existed and the exhibit “Faceless Portraits Transcending Time,” features images that don’t bear much or, in some cases, any resemblance to human beings. Maybe this is considered a dull question by people in the know but I’m an outsider and I found the paradox: portraits of nonexistent people or nonpeople kind of interesting.

BTW, I double-checked my assumption about portraits and found this definition in the Portrait Wikipedia entry (Note: Links have been removed),

A portrait is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person [emphasis mine], in which the face and its expression is predominant. The intent is to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the person. For this reason, in photography a portrait is generally not a snapshot, but a composed image of a person in a still position. A portrait often shows a person looking directly at the painter or photographer, in order to most successfully engage the subject with the viewer.

So, portraits that aren’t portraits give rise to some philosophical questions but Bogost either didn’t want to jump into that rabbit hole (segue into yet another topic) or, as I hinted earlier, may have assumed his audience had previous experience of those kinds of discussions.

Vancouver (Canada) and a ‘portraiture’ exhibit at the Rennie Museum

By one of life’s coincidences, Vancouver’s Rennie Museum had an exhibit (February 16 – June 15, 2019) that illuminates questions about art collecting and portraiture, From a February 7, 2019 Rennie Museum news release,

February 7, 2019

Press Release | Spring 2019: Collected Works

By rennie museumrennie museum is pleased to present Spring 2019: Collected Works, a group exhibition encompassing the mediums of photography, painting and film. A portraiture of the collecting spirit [emphasis mine], the works exhibited invite exploration of what collected objects, and both the considered and unintentional ways they are displayed, inform us. Featuring the works of four artists—Andrew Grassie, William E. Jones, Louise Lawler and Catherine Opie—the exhibition runs from February 16 to June 15, 2019.

Four exquisite paintings by Scottish painter Andrew Grassie detailing the home and private storage space of a major art collector provide a peek at how the passionately devoted integrates and accommodates the physical embodiments of such commitment into daily life. Grassie’s carefully constructed, hyper-realistic images also pose the question, “What happens to art once it’s sold?” In the transition from pristine gallery setting to idiosyncratic private space, how does the new context infuse our reading of the art and how does the art shift our perception of the individual?

Furthering the inquiry into the symbiotic exchange between possessor and possession, a selection of images by American photographer Louise Lawler depicting art installed in various private and public settings question how the bilateral relationship permeates our interpretation when the collector and the collected are no longer immediately connected. What does de-acquisitioning an object inform us and how does provenance affect our consideration of the art?

The question of legacy became an unexpected facet of 700 Nimes Road (2010-2011), American photographer Catherine Opie’s portrait of legendary actress Elizabeth Taylor. Opie did not directly photograph Taylor for any of the fifty images in the expansive portfolio. Instead, she focused on Taylor’s home and the objects within, inviting viewers to see—then see beyond—the façade of fame and consider how both treasures and trinkets act as vignettes to the stories of a life. Glamorous images of jewels and trophies juxtapose with mundane shots of a printer and the remote-control user manual. Groupings of major artworks on the wall are as illuminating of the home’s mistress as clusters of personal photos. Taylor passed away part way through Opie’s project. The subsequent photos include Taylor’s mementos heading off to auction, raising the question, “Once the collections that help to define someone are disbursed, will our image of that person lose focus?”

In a similar fashion, the twenty-two photographs in Villa Iolas (1982/2017), by American artist and filmmaker William E. Jones, depict the Athens home of iconic art dealer and collector Alexander Iolas. Taken in 1982 by Jones during his first travels abroad, the photographs of art, furniture and antiquities tell a story of privilege that contrast sharply with the images Jones captures on a return visit in 2016. Nearly three decades after Iolas’s 1989 death, his home sits in dilapidation, looted and vandalized. Iolas played an extraordinary role in the evolution of modern art, building the careers of Max Ernst, Yves Klein and Giorgio de Chirico. He gave Andy Warhol his first solo exhibition and was a key advisor to famed collectors John and Dominique de Menil. Yet in the years since his death, his intention of turning his home into a modern art museum as a gift to Greece, along with his reputation, crumbled into ruins. The photographs taken by Jones during his visits in two different eras are incorporated into the film Fall into Ruin (2017), along with shots of contemporary Athens and antiquities on display at the National Archaeological Museum.

“I ask a lot of questions about how portraiture functions—what is there to describe the person or time we live in or a certain set of politics…”

– Catherine Opie, The Guardian, Feb 9, 2016We tend to think of the act of collecting as a formal activity yet it can happen casually on a daily basis, often in trivial ways. While we readily acknowledge a collector consciously assembling with deliberate thought, we give lesser consideration to the arbitrary accumulations that each of us accrue. Be it master artworks, incidental baubles or random curios, the objects we acquire and surround ourselves with tell stories of who we are.

Andrew Grassie (Scotland, b. 1966) is a painter known for his small scale, hyper-realist works. He has been the subject of solo exhibitions at the Tate Britain; Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh; institut supérieur des arts de Toulouse; and rennie museum, Vancouver, Canada. He lives and works in London, England.William E. Jones (USA, b. 1962) is an artist, experimental film-essayist and writer. Jones’s work has been the subject of retrospectives at Tate Modern, London; Anthology Film Archives, New York; Austrian Film Museum, Vienna; and, Oberhausen Short Film Festival. He is a recipient of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship and the Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. He lives and works in Los Angeles, USA.

Louise Lawler (USA, b. 1947) is a photographer and one of the foremost members of the Pictures Generation. Lawler was the subject of a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2017. She has held exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; National Museum of Art, Oslo; and Musée d’Art Moderne de La Ville de Paris. She lives and works in New York.

Catherine Opie (USA, b. 1961) is a photographer and educator. Her work has been exhibited at Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio; Henie Onstad Art Center, Oslo; Los the Angeles County Museum of Art; Portland Art Museum; and the Guggenheim Museum, New York. She is the recipient of United States Artist Fellowship, Julius Shulman’s Excellence in Photography Award, and the Smithsonian’s Archive of American Art Medal. She lives and works in Los Angeles.

rennie museum opened in October 2009 in historic Wing Sang, the oldest structure in Vancouver’s Chinatown, to feature dynamic exhibitions comprising only of art drawn from rennie collection. Showcasing works by emerging and established international artists, the exhibits, accompanied by supporting catalogues, are open free to the public through engaging guided tours. The museum’s commitment to providing access to arts and culture is also expressed through its education program, which offers free age-appropriate tours and customized workshops to children of all ages.

rennie collection is a globally recognized collection of contemporary art that focuses on works that tackle issues related to identity, social commentary and injustice, appropriation, and the nature of painting, photography, sculpture and film. Currently the collection includes works by over 370 emerging and established artists, with over fifty collected in depth. The Vancouver based collection engages actively with numerous museums globally through a robust, artist-centric, lending policy.

So despite the Wikipedia definition, it seems that portraits don’t always feature people. While Bogost didn’t jump into that particular rabbit hole, he did touch on the business side of art.

What about intellectual property?

Bogost doesn’t explicitly discuss this particular issue. It’s a big topic so I’m touching on it only lightly, if an artist works* with an AI, the question as to ownership of the artwork could prove thorny. Is the copyright owner the computer scientist or the artist or both? Or does the AI artist-agent itself own the copyright? That last question may not be all that farfetched. Sophia, a social humanoid robot, has occasioned thought about ‘personhood.’ (Note: The robots mentioned in this posting have artificial intelligence.) From the Sophia (robot) Wikipedia entry (Note: Links have been removed),

Sophia has been interviewed in the same manner as a human, striking up conversations with hosts. Some replies have been nonsensical, while others have impressed interviewers such as 60 Minutes’ Charlie Rose.[12] In a piece for CNBC, when the interviewer expressed concerns about robot behavior, Sophia joked that he had “been reading too much Elon Musk. And watching too many Hollywood movies”.[27] Musk tweeted that Sophia should watch The Godfather and asked “what’s the worst that could happen?”[28][29] Business Insider’s chief UK editor Jim Edwards interviewed Sophia, and while the answers were “not altogether terrible”, he predicted it was a step towards “conversational artificial intelligence”.[30] At the 2018 Consumer Electronics Show, a BBC News reporter described talking with Sophia as “a slightly awkward experience”.[31]

On October 11, 2017, Sophia was introduced to the United Nations with a brief conversation with the United Nations Deputy Secretary-General, Amina J. Mohammed.[32] On October 25, at the Future Investment Summit in Riyadh, the robot was granted Saudi Arabian citizenship [emphasis mine], becoming the first robot ever to have a nationality.[29][33] This attracted controversy as some commentators wondered if this implied that Sophia could vote or marry, or whether a deliberate system shutdown could be considered murder. Social media users used Sophia’s citizenship to criticize Saudi Arabia’s human rights record. In December 2017, Sophia’s creator David Hanson said in an interview that Sophia would use her citizenship to advocate for women’s rights in her new country of citizenship; Newsweek criticized that “What [Hanson] means, exactly, is unclear”.[34] On November 27, 2018 Sophia was given a visa by Azerbaijan while attending Global Influencer Day Congress held in Baku. December 15, 2018 Sophia was appointed a Belt and Road Innovative Technology Ambassador by China'[35]

As for an AI artist-agent’s intellectual property rights , I have a July 10, 2017 posting featuring that question in more detail. Whether you read that piece or not, it seems obvious that artists might hesitate to call an AI agent, a partner rather than a medium of expression. After all, a partner (and/or the computer scientist who developed the programme) might expect to share in property rights and profits but paint, marble, plastic, and other media used by artists don’t have those expectations.

Moving slightly off topic , in my July 10, 2017 posting I mentioned a competition (literary and performing arts rather than visual arts) called, ‘Dartmouth College and its Neukom Institute Prizes in Computational Arts’. It was started in 2016 and, as of 2018, was still operational under this name: Creative Turing Tests. Assuming there’ll be contests for prizes in 2019, there’s (from the contest site) [1] PoetiX, competition in computer-generated sonnet writing; [2] Musical Style, composition algorithms in various styles, and human-machine improvisation …; and [3] DigiLit, algorithms able to produce “human-level” short story writing that is indistinguishable from an “average” human effort. You can find the contest site here.

*’worsk’ corrected to ‘works’ on June 9, 2022