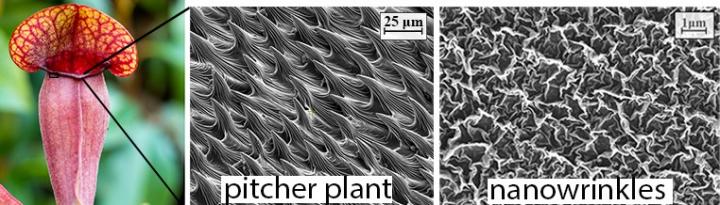

This is an example of what the researchers mean by ‘nanowrinkles’,

Caption: The Nepenthes pitcher plant (left) and its nanowrinkled ‘mouth’ (centre) inspired the engineered nanomaterial (right). Credit: Sydney Nano Courtesy: University of Sydney

As for ‘biofouling’, here’s my rough and ready description for anyone who might find it helpful, if you’ve been to the beach and slipped on some rocks, that slip was probably due to a biofilm and biofilm contributes to ‘biofouling’.

Australian scientists have announced research on a new technique for the eradication of biofouling according to a January 17, 2018 University of Sydney press release (also on EurekAlert but dated Jan. 16, 2018),

Sydney scientists have developed nanowrinkled coatings that could avoid the build-up of damaging biological material and save some of the $320 million annually spent by the Australian shipping industry because of biofouling.

A team of chemistry researchers from the University of Sydney Nano Institute has developed nanostructured surface coatings that have anti-fouling properties without using any toxic components.

Biofouling – the build-up of damaging biological material – is a huge economic issue, costing the aquaculture and shipping industries billions of dollars a year in maintenance and extra fuel usage. It is estimated that the increased drag on ship hulls due to biofouling costs the shipping industry in Australia $320 million a year a b.

Since the banning of the toxic anti-fouling agent tributyltin, the need for new non-toxic methods to stop marine biofouling has been pressing.

Leader of the research team, Associate Professor Chiara Neto, said: “We are keen to understand how these surfaces work and also push the boundaries of their application, especially for energy efficiency. Slippery coatings are expected to be drag-reducing, which means that objects, such as ships, could move through water with much less energy required.”

The new materials were tested tied to shark netting in Sydney’s Watson Bay, showing that the nanomaterials were efficient at resisting biofouling in a marine environment.

The research has been published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

The new coating uses ‘nanowrinkles’ inspired by the carnivorous Nepenthes pitcher plant. The plant traps a layer of water on the tiny structures around the rim of its opening. This creates a slippery layer causing insects to aquaplane on the surface, before they slip into the pitcher where they are digested.

Nanostructures utilise materials engineered at the scale of billionths of a metre – 100,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair. Associate Professor Neto’s group at Sydney Nano is developing nanoscale materials for future development in industry.

Biofouling can occur on any surface that is wet for a long period of time, for example aquaculture nets, marine sensors and cameras, and ship hulls. The slippery surface developed by the Neto group stops the initial adhesion of bacteria, inhibiting the formation of a biofilm from which larger marine fouling organisms can grow.

The interdisciplinary University of Sydney team included biofouling expert Professor Truis Smith-Palmer of St Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, Canada, who was on sabbatical visit to the Neto group for a year, partially funded by the Faculty of Science scheme for visiting women.

In the lab, the slippery surfaces resisted almost all fouling from a common species of marine bacteria, while control Teflon samples without the lubricating layer were completely fouled. Not satisfied with testing the surfaces under highly controlled lab conditions with only one type of bacteria the team also tested the surfaces in the ocean, with the help of marine biologist Professor Ross Coleman.

Test surfaces were attached to swimming nets at Watsons Bay baths in Sydney Harbour for a period of seven weeks. In the much harsher marine environment, the slippery surfaces were still very efficient at resisting fouling.

The antifouling coatings are mouldable and transparent, making their application ideal for underwater cameras and sensors.

Sources for economic data:

a) M. P. Schultz, J. A. Bendick, E. R. Holm, W. M. Hertel, Biofouling 2011, 27, 87-98;

b) Western Australia Departmet of Fisheries, in Fisheries Occasional Publication No. 115, 2012

Even though there’s a link to the paper in the excerpt, here’s a citation and another link to the paper,

Marine Antifouling Behavior of Lubricant-Infused Nanowrinkled Polymeric Surfaces by

Cameron S. Ware, Truis Smith-Palmer, Sam Peppou-Chapman, Liam R. J. Scarratt, Erin M. Humphries, Daniel Balzer, and Chiara Neto. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, Article ASAP DOI: 10.1021/acsami.7b14736 Publication Date (Web): December 18, 2017Copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.