Being able to analyze Twitter messages (tweets) in real-time is amazing given what I wrote in this January 16, 2013 posting titled: “Researching tweets (the Twitter kind)” about the US Library of Congress and its attempts to access tweets for scholars,”

At least one of the reasons no one has received access to the tweets is that a single search of the archived (2006- 2010) tweets alone would take 24 hours, [emphases mine] …

So, bravo to the researchers at the University of Vermont (UVM). A July 16, 2021 news item on ScienceDaily makes the announcement,

For thousands of years, people looked into the night sky with their naked eyes — and told stories about the few visible stars. Then we invented telescopes. In 1840, the philosopher Thomas Carlyle claimed that “the history of the world is but the biography of great men.” Then we started posting on Twitter.

Now scientists have invented an instrument to peer deeply into the billions and billions of posts made on Twitter since 2008 — and have begun to uncover the vast galaxy of stories that they contain.

A July 15, 2021 UVM news release (also on EurekAlert but published on July 16, 2021) by Joshua Brown, which originated the news item, provides more detail abut the work,

“We call it the Storywrangler,” says Thayer Alshaabi, a doctoral student at the University of Vermont who co-led the new research. “It’s like a telescope to look — in real time — at all this data that people share on social media. We hope people will use it themselves, in the same way you might look up at the stars and ask your own questions.”

The new tool can give an unprecedented, minute-by-minute view of popularity, from rising political movements to box office flops; from the staggering success of K-pop to signals of emerging new diseases.

The story of the Storywrangler — a curation and analysis of over 150 billion tweets–and some of its key findings were published on July 16 [2021] in the journal Science Advances.

EXPRESSIONS OF THE MANY

The team of eight scientists who invented Storywrangler — from the University of Vermont, Charles River Analytics, and MassMutual Data Science [emphasis mine]– gather about ten percent of all the tweets made every day, around the globe. For each day, they break these tweets into single bits, as well as pairs and triplets, generating frequencies from more than a trillion words, hashtags, handles, symbols and emoji, like “Super Bowl,” “Black Lives Matter,” “gravitational waves,” “#metoo,” “coronavirus,” and “keto diet.”

“This is the first visualization tool that allows you to look at one-, two-, and three-word phrases, across 150 different languages [emphasis mine], from the inception of Twitter to the present,” says Jane Adams, a co-author on the new study who recently finished a three-year position as a data-visualization artist-in-residence at UVM’s Complex Systems Center.

The online tool, powered by UVM’s supercomputer at the Vermont Advanced Computing Core, provides a powerful lens for viewing and analyzing the rise and fall of words, ideas, and stories each day among people around the world. “It’s important because it shows major discourses as they’re happening,” Adams says. “It’s quantifying collective attention.” Though Twitter does not represent the whole of humanity, it is used by a very large and diverse group of people, which means that it “encodes popularity and spreading,” the scientists write, giving a novel view of discourse not just of famous people, like political figures and celebrities, but also the daily “expressions of the many,” the team notes.

In one striking test of the vast dataset on the Storywrangler, the team showed that it could be used to potentially predict political and financial turmoil. They examined the percent change in the use of the words “rebellion” and “crackdown” in various regions of the world. They found that the rise and fall of these terms was significantly associated with change in a well-established index of geopolitical risk for those same places.

WHAT’S HAPPENING?

The global story now being written on social media brings billions of voices — commenting and sharing, complaining and attacking — and, in all cases, recording — about world wars, weird cats, political movements, new music, what’s for dinner, deadly diseases, favorite soccer stars, religious hopes and dirty jokes.

“The Storywrangler gives us a data-driven way to index what regular people are talking about in everyday conversations, not just what reporters or authors have chosen; it’s not just the educated or the wealthy or cultural elites,” says applied mathematician Chris Danforth, a professor at the University of Vermont who co-led the creation of the StoryWrangler with his colleague Peter Dodds. Together, they run UVM’s Computational Story Lab.

“This is part of the evolution of science,” says Dodds, an expert on complex systems and professor in UVM’s Department of Computer Science. “This tool can enable new approaches in journalism, powerful ways to look at natural language processing, and the development of computational history.”

How much a few powerful people shape the course of events has been debated for centuries. But, certainly, if we knew what every peasant, soldier, shopkeeper, nurse, and teenager was saying during the French Revolution, we’d have a richly different set of stories about the rise and reign of Napoleon. “Here’s the deep question,” says Dodds, “what happened? Like, what actually happened?”

GLOBAL SENSOR

The UVM team, with support from the National Science Foundation [emphasis mine], is using Twitter to demonstrate how chatter on distributed social media can act as a kind of global sensor system — of what happened, how people reacted, and what might come next. But other social media streams, from Reddit to 4chan to Weibo, could, in theory, also be used to feed Storywrangler or similar devices: tracing the reaction to major news events and natural disasters; following the fame and fate of political leaders and sports stars; and opening a view of casual conversation that can provide insights into dynamics ranging from racism to employment, emerging health threats to new memes.

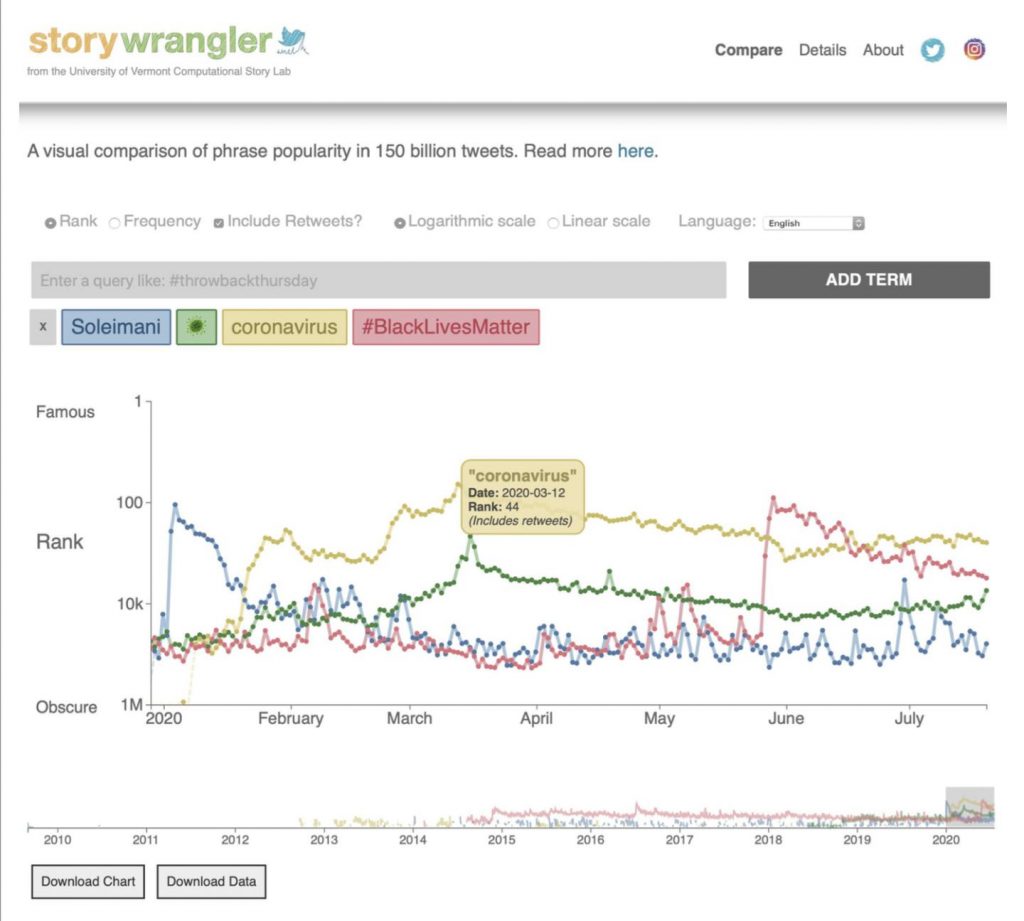

In the new Science Advances study, the team presents a sample from the Storywrangler’s online viewer, with three global events highlighted: the death of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani; the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic; and the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. The Storywrangler dataset records a sudden spike of tweets and retweets using the term “Soleimani” on January 3, 2020, when the United States assassinated the general; the strong rise of “coronavirus” and the virus emoji over the spring of 2020 as the disease spread; and a burst of use of the hashtag “#BlackLivesMatter” on and after May 25, 2020, the day George Floyd was murdered.

“There’s a hashtag that’s being invented while I’m talking right now,” says UVM’s Chris Danforth. “We didn’t know to look for that yesterday, but it will show up in the data and become part of the story.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Storywrangler: A massive exploratorium for sociolinguistic, cultural, socioeconomic, and and political timelines using Twitter by Thayer Alshaabi, Jane L. Adams, Michael V. Arnold, Joshua R. Minot, David R. Dewhurst, Andrew J. Reagan, Christopher M. Danforth and Peter Sheridan Dodds. Science Advances 16 Jul 2021: Vol. 7, no. 29, eabe6534DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abe6534 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abe6534

This paper is open access.

A couple of comments

I’m glad to see they are looking at phrases in many different languages. Although I do experience some hesitation when I consider the two companies involved in this research with the University of Vermont.

Charles River Analytics and MassMutual Data Science would not have been my first guess for corporate involvement but on re-examining the subhead and noting this: “potentially predict political and financial turmoil”, they make perfect sense. Charles River Analytics provides “Solutions to serve the warfighter …”, i.e., soldiers/the military, and MassMutual is an insurance company with a dedicated ‘data science space’ (from the MassMutual Explore Careers Data Science webpage),

What are some key projects that the Data Science team works on?

Data science works with stakeholders throughout the enterprise to automate or support decision making when outcomes are unknown. We help determine the prospective clients that MassMutual should market to, the risk associated with life insurance applicants, and which bonds MassMutual should invest in. [emphases mine]

Of course. The military and financial services. Delightfully, this research is at least partially (mostly?) funded on the public dime, the US National Science Foundation.

![Rainbow over Durham Cathedral by StephieBee [downloaded from https://www.flickr.com/photos/visitengland/galleries/72157625178514241/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/DurhamCathedralRainbow-300x168.jpg)