I’m not sure how I feel about an electrified rose but it is strangely fascinating. Here’s more from a July 29, 2019 news item on Nanowerk,

Martin Thuo of Iowa State University and the Ames Laboratory clicked through the photo gallery for one of his research projects.

How about this one? There was a rose with metal traces printed on a delicate petal.

Or this? A curled sheet of paper with a flexible, programmable LED display.

Maybe this? A gelatin cylinder with metal traces printed across the top.

…

A July 26, 2019 Iowa State University news release (also on EurekAlert but published on July 29, 2019), which originated the news item,

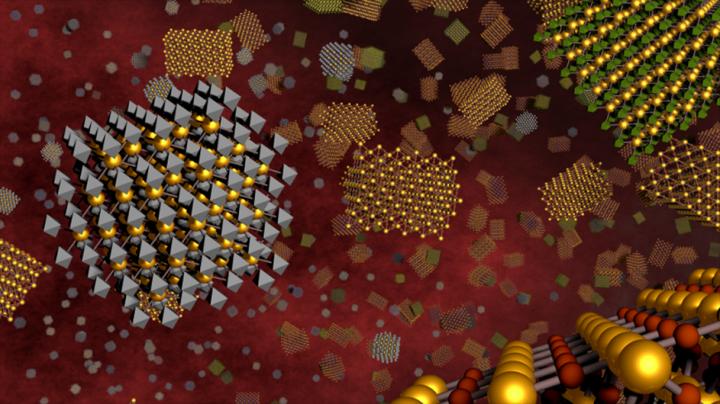

All those photos showed the latest application of undercooled metal technology developed by Thuo and his research group. The technology features liquid metal (in this case Field’s metal, an alloy of bismuth, indium and tin) trapped below its melting point in polished, oxide shells, creating particles about 10 millionths of a meter across.

When the shells are broken – with mechanical pressure or chemical dissolving – the metal inside flows and solidifies, creating a heat-free weld or, in this case, printing conductive, metallic lines and traces on all kinds of materials, everything from a concrete wall to a leaf.

That could have all kinds of applications, including sensors to measure the structural integrity of a building or the growth of crops. The technology was also tested in paper-based remote controls that read changes in electrical currents when the paper is curved. Engineers also tested the technology by making electrical contacts for solar cells and by screen printing conductive lines on gelatin, a model for soft biological tissues, including the brain.

“This work reports heat-free, ambient fabrication of metallic conductive interconnects and traces on all types of substrates,” Thuo and a team of researchers wrote in a paper describing the technology recently published online by the journal Advanced Functional Materials.

Thuo – an assistant professor of materials science and engineering at Iowa State, an associate of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory and a co-founder of the Ames startup SAFI-Tech Inc. that’s commercializing the liquid-metal particles – is the lead author. Co-authors are Andrew Martin, a former undergraduate in Thuo’s lab and now an Iowa State doctoral student in materials science and engineering; Boyce Chang, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, who earned his doctoral degree at Iowa State Zachariah Martin, Dipak Paramanik and Ian Tevis, of SAFI-Tech; Christophe Frankiewicz, a co-founder of Sep-All in Ames and a former Iowa State postdoctoral research associate; and Souvik Kundu, an Iowa State graduate student in electrical and computer engineering.

The project was supported by university startup funds to establish Thuo’s research lab at Iowa State, Thuo’s Black & Veatch faculty fellowship and a National Science Foundation Small Business Innovation Research grant.Thuo said he launched the project three years ago as a teaching exercise.

“I started this with undergraduate students,” he said. “I thought it would be fun to get students to make something like this. It’s a really beneficial teaching tool because you don’t need to solve 2 million equations to do sophisticated science.”

And once students learned to use a few metal-processing tools, they started solving some of the technical challenges of flexible, metal electronics.

“The students discovered ways of dealing with metal and that blossomed into a million ideas,” Thuo said. “And now we can’t stop.”

And so the researchers have learned how to effectively bond metal traces to everything from water-repelling rose petals to watery gelatin. Based on what they now know, Thuo said it would be easy for them to print metallic traces on ice cubes or biological tissue.

All the experiments “highlight the versatility of this approach,” the researchers wrote in their paper, “allowing a multitude of conductive products to be fabricated without damaging the base material.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Heat‐Free Fabrication of Metallic Interconnects for Flexible/Wearable Devices by Andrew Martin, Boyce S. Chang, Zachariah Martin, Dipak Paramanik, Christophe Frankiewicz, Souvik Kundu, Ian D. Tevis, Martin Thuo. Advanced Functional Materials Online Version of Record before inclusion in an issue 1903687 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201903687 First published online: 15 July 2019

This paper is behind a paywall.