A Nov. 4, 2014 news item on Phys.org features some research in Utah on the use of carbon nanotubes for sensing devices,

University of Utah engineers have developed a new type of carbon nanotube material for handheld sensors that will be quicker and better at sniffing out explosives, deadly gases and illegal drugs.

A carbon nanotube is a cylindrical material that is a hexagonal or six-sided array of carbon atoms rolled up into a tube. Carbon nanotubes are known for their strength and high electrical conductivity and are used in products from baseball bats and other sports equipment to lithium-ion batteries and touchscreen computer displays.

Vaporsens, a university spin-off company, plans to build a prototype handheld sensor by year’s end and produce the first commercial scanners early next year, says co-founder Ling Zang, a professor of materials science and engineering and senior author of a study of the technology published online Nov. 4 [2014] in the journal Advanced Materials.

The new kind of nanotubes also could lead to flexible solar panels that can be rolled up and stored or even “painted” on clothing such as a jacket, he adds.

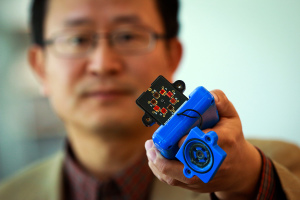

Here’s Ling Zang holding a prototype of the device,

Ling Zang, a University of Utah professor of materials science and engineering, holds a prototype detector that uses a new type of carbon nanotube material for use in handheld scanners to detect explosives, toxic chemicals and illegal drugs. Zang and colleagues developed the new material, which will make such scanners quicker and more sensitive than today’s standard detection devices. Ling’s spinoff company, Vaporsens, plans to produce commercial versions of the new kind of scanner early next year. Courtesy: University of Utah

A Nov. 4, 2014 University of Utah news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail about the research,

Zang and his team found a way to break up bundles of the carbon nanotubes with a polymer and then deposit a microscopic amount on electrodes in a prototype handheld scanner that can detect toxic gases such as sarin or chlorine, or explosives such as TNT.

When the sensor detects molecules from an explosive, deadly gas or drugs such as methamphetamine, they alter the electrical current through the nanotube materials, signaling the presence of any of those substances, Zang says.

“You can apply voltage between the electrodes and monitor the current through the nanotube,” says Zang, a professor with USTAR, the Utah Science Technology and Research economic development initiative. “If you have explosives or toxic chemicals caught by the nanotube, you will see an increase or decrease in the current.”

By modifying the surface of the nanotubes with a polymer, the material can be tuned to detect any of more than a dozen explosives, including homemade bombs, and about two-dozen different toxic gases, says Zang. The technology also can be applied to existing detectors or airport scanners used to sense explosives or chemical threats.

Zang says scanners with the new technology “could be used by the military, police, first responders and private industry focused on public safety.”

Unlike the today’s detectors, which analyze the spectra of ionized molecules of explosives and chemicals, the Utah carbon-nanotube technology has four advantages:

• It is more sensitive because all the carbon atoms in the nanotube are exposed to air, “so every part is susceptible to whatever it is detecting,” says study co-author Ben Bunes, a doctoral student in materials science and engineering.

• It is more accurate and generates fewer false positives, according to lab tests.

• It has a faster response time. While current detectors might find an explosive or gas in minutes, this type of device could do it in seconds, the tests showed.

• It is cost-effective because the total amount of the material used is microscopic.

This study was funded by the Department of Homeland Security, Department of Defense, National Science Foundation and NASA. …

Here’s a link to and a citation for the research paper,

Photodoping and Enhanced Visible Light Absorption in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Functionalized with a Wide Band Gap Oligomer by Benjamin R. Bunes, Miao Xu, Yaqiong Zhang, Dustin E. Gross, Avishek Saha, Daniel L. Jacobs, Xiaomei Yang, Jeffrey S. Moore, and Ling Zang. Advanced Materials DOI: 10.1002/adma.201404112 Article first published online: 4 NOV 2014

© 2014 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

This paper is behind a paywall.

For anyone curious about Vaporsens, you can find more here.

![Credit: Goaly (?) [downloaded from http://www.instructables.com/id/Building-A-Ship-In-A-Bottle/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ShipInABottle-300x187.jpg)