Researcher Miguel Nicolelis and his colleagues at Duke University have implanted a neuroprosthetic device in the portion of a rat’s brain related to touch that allows the rats to see infrared light. From the Feb. 12, 2013 news release on EurekAlert,

Researchers have given rats the ability to “touch” infrared light, normally invisible to them, by fitting them with an infrared detector wired to microscopic electrodes implanted in the part of the mammalian brain that processes tactile information. The achievement represents the first time a brain-machine interface has augmented a sense in adult animals, said Duke University neurobiologist Miguel Nicolelis, who led the research team.

The experiment also demonstrated for the first time that a novel sensory input could be processed by a cortical region specialized in another sense without “hijacking” the function of this brain area said Nicolelis. This discovery suggests, for example, that a person whose visual cortex was damaged could regain sight through a neuroprosthesis implanted in another cortical region, he said.

Although the initial experiments tested only whether rats could detect infrared light, there seems no reason that these animals in the future could not be given full-fledged infrared vision, said Nicolelis. For that matter, cortical neuroprostheses could be developed to give animals or humans the ability to see in any region of the electromagnetic spectrum, or even magnetic fields. “We could create devices sensitive to any physical energy,” he said. “It could be magnetic fields, radio waves, or ultrasound. We chose infrared initially because it didn’t interfere with our electrophysiological recordings.”

Interestingly, the research was supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (as per the news release).

The researchers have more to say about what they’re doing,

“The philosophy of the field of brain-machine interfaces has until now been to attempt to restore a motor function lost to lesion or damage of the central nervous system,” said Thomson, [Eric Thomson] first author of the study. “This is the first paper in which a neuroprosthetic device was used to augment function—literally enabling a normal animal to acquire a sixth sense.”

Here’s how they conducted the research,

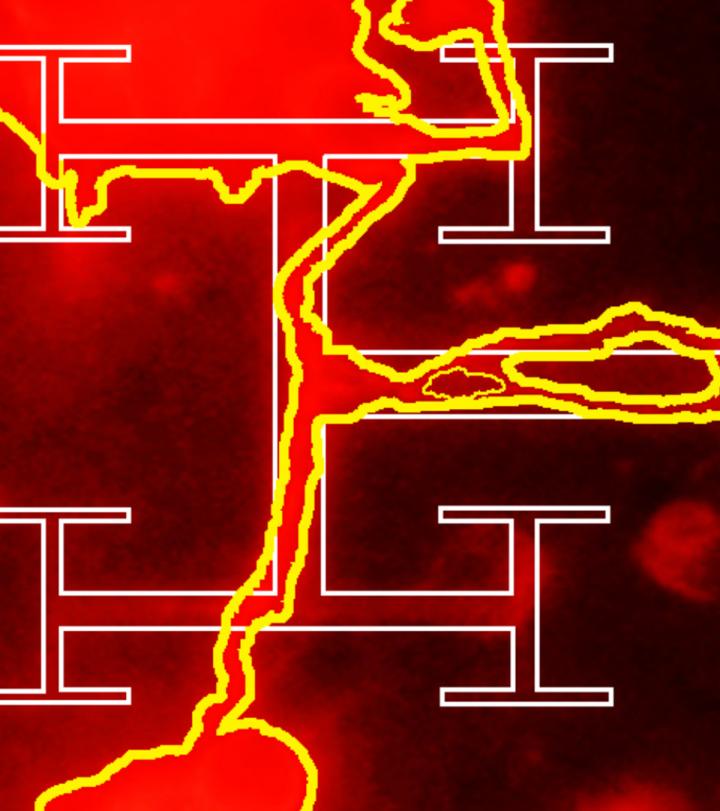

The mammalian retina is blind to infrared light, and mammals cannot detect any heat generated by the weak infrared light used in the studies. In their experiments, the researchers used a test chamber that contained three light sources that could be switched on randomly. Using visible LED lights, they first taught each rat to choose the active light source by poking its nose into an attached port to receive a reward of a sip of water.

After training the rats, the researchers implanted in their brains an array of stimulating microelectrodes, each roughly a tenth the diameter of a human hair. The microelectrodes were implanted in the cortical region that processes touch information from the animals’ facial whiskers.

Attached to the microelectrodes was an infrared detector affixed to the animals’ foreheads. The system was programmed so that orientation toward an infrared light would trigger an electrical signal to the brain. The signal pulses increased in frequency with the intensity and proximity of the light.

The researchers returned the animals to the test chamber, gradually replacing the visible lights with infrared lights. At first in infrared trials, when a light was switched on the animals would tend to poke randomly at the reward ports and scratch at their faces, said Nicolelis. This indicated that they were initially interpreting the brain signals as touch. However, over about a month, the animals learned to associate the brain signal with the infrared source. They began to actively “forage” for the signal, sweeping their heads back and forth to guide themselves to the active light source. Ultimately, they achieved a near-perfect score in tracking and identifying the correct location of the infrared light source.

To ensure that the animals were really using the infrared detector and not their eyes to sense the infrared light, the researchers conducted trials in which the light switched on, but the detector sent no signal to the brain. In these trials, the rats did not react to the infrared light.

Their finding could have an impact on notions of mammalian brain plasticity,

A key finding, said Nicolelis, was that enlisting the touch cortex for light detection did not reduce its ability to process touch signals. “When we recorded signals from the touch cortex of these animals, we found that although the cells had begun responding to infrared light, they continued to respond to whisker touch. It was almost like the cortex was dividing itself evenly so that the neurons could process both types of information.

This finding of brain plasticity is in contrast with the “optogenetic” approach to brain stimulation, which holds that a particular neuronal cell type should be stimulated to generate a desired neurological function. Rather, said Nicolelis, the experiments demonstrate that a broad electrical stimulation, which recruits many distinct cell types, can drive a cortical region to adapt to a new source of sensory input.

All of this work is part of Nicolelis’ larger project ‘Walk Again’ which is mentioned in my March 16, 2012 posting and includes a reference to some ethical issues raised by the work. Briefly, Nicolelis and an international team of collaborators are developing a brain-machine interface that will enable full mobility for people who are severely paralyzed. From the news release,

The Walk Again Project has recently received a $20 million grant from FINEP, a Brazilian research funding agency to allow the development of the first brain-controlled whole body exoskeleton aimed at restoring mobility in severely paralyzed patients. A first demonstration of this technology is expected to happen in the opening game of the 2014 Soccer World Cup in Brazil.

Expanding sensory abilities could also enable a new type of feedback loop to improve the speed and accuracy of such exoskeletons, said Nicolelis. For example, while researchers are now seeking to use tactile feedback to allow patients to feel the movements produced by such “robotic vests,” the feedback could also be in the form of a radio signal or infrared light that would give the person information on the exoskeleton limb’s position and encounter with objects.

There’s more information including videos about the work with infrared light and rats at the Nicolelis Lab website. Here’s a citation for and link to the team’s research paper,

Perceiving invisible light through a somatosensory cortical prosthesis by Eric E. Thomson, Rafael Carra, & Miguel A.L. Nicolelis. Nature Communications Published 12 Feb 2013 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms2497

Meanwhile, the US Food and Drug Administraton (FDA) has approved the first commercial artificial retina, from the Feb. 14, 2013 news release,

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted market approval to an artificial retina technology today, the first bionic eye to be approved for patients in the United States. The prosthetic technology was developed in part with support from the National Science Foundation (NSF).

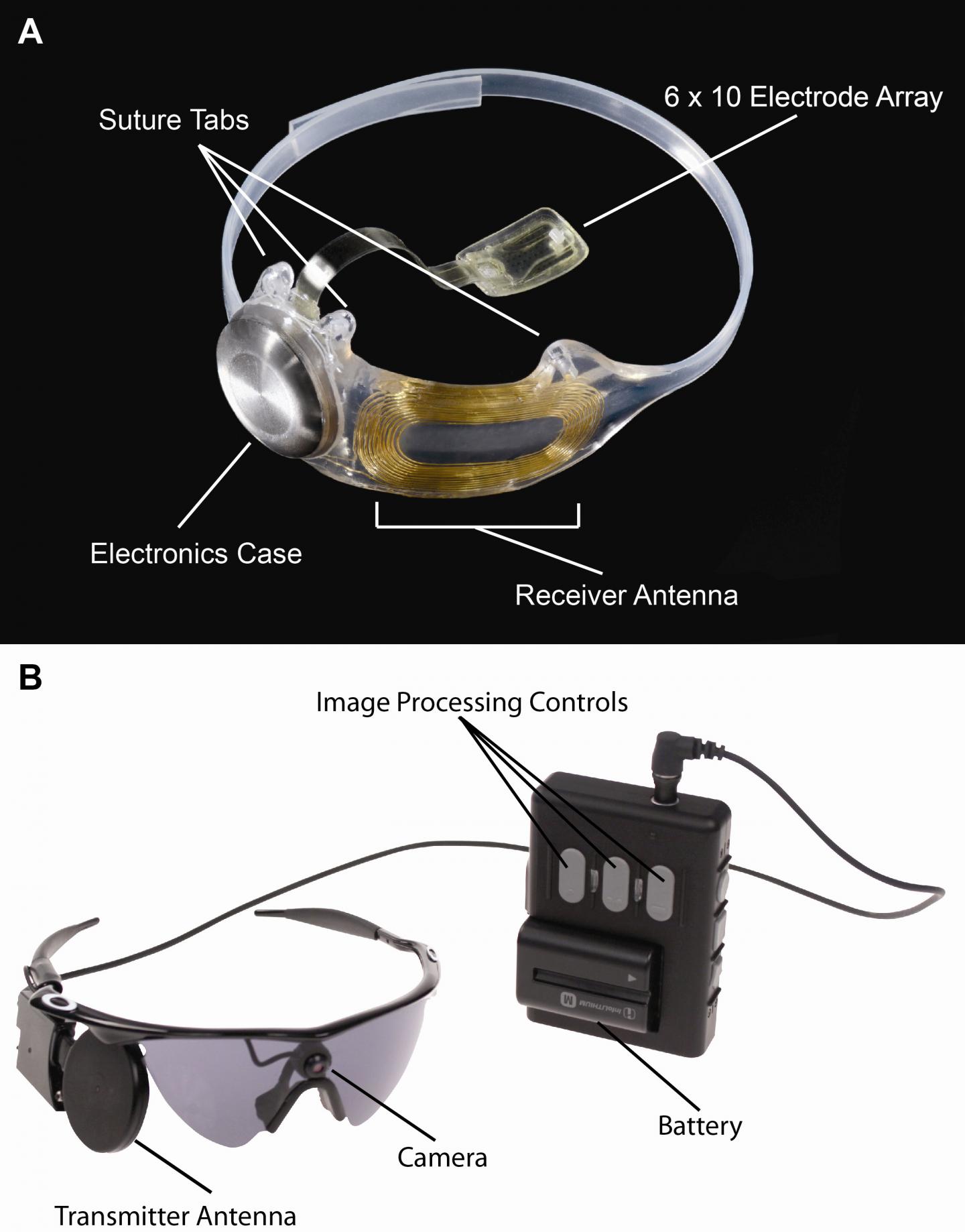

The device, called the Argus® II Retinal Prosthesis System, transmits images from a small, eye-glass-mounted camera wirelessly to a microelectrode array implanted on a patient’s damaged retina. The array sends electrical signals via the optic nerve, and the brain interprets a visual image.

The FDA approval currently applies to individuals who have lost sight as a result of severe to profound retinitis pigmentosa (RP), an ailment that affects one in every 4,000 Americans. The implant allows some individuals with RP, who are completely blind, to locate objects, detect movement, improve orientation and mobility skills and discern shapes such as large letters.

The Argus II is manufactured by, and will be distributed by, Second Sight Medical Products of Sylmar, Calif., which is part of the team of scientists and engineers from the university, federal and private sectors who spent nearly two decades developing the system with public and private investment.

Scientists are often compelled to do research in an area inspired by family,

“Seeing my grandmother go blind motivated me to pursue ophthalmology and biomedical engineering to develop a treatment for patients for whom there was no foreseeable cure,” says the technology’s co-developer, Mark Humayun, associate director of research at the Doheny Eye Institute at the University of Southern California and director of the NSF Engineering Research Center for Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems (BMES). …”

There’s also been considerable government investment,

The effort by Humayun and his colleagues has received early and continuing support from NSF, the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Energy, with grants totaling more than $100 million. The private sector’s support nearly matched that of the federal government.

“The retinal implant exemplifies how NSF grants for high-risk, fundamental research can directly result in ground-breaking technologies decades later,” said Acting NSF Assistant Director for Engineering Kesh Narayanan. “In collaboration with the Second Sight team and the courageous patients who volunteered to have experimental surgery to implant the first-generation devices, the researchers of NSF’s Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems Engineering Research Center are developing technologies that may ultimately have as profound an impact on blindness as the cochlear implant has had for hearing loss.”

Leaving aside controversies about cochlear implants and the possibility of such controversies with artificial retinas (bionic eyes), it’s interesting to note that this device is dependent on an external camera,

The researchers’ efforts have bridged cellular biology–necessary for understanding how to stimulate the retinal ganglion cells without permanent damage–with microelectronics, which led to the miniaturized, low-power integrated chip for performing signal conversion, conditioning and stimulation functions. The hardware was paired with software processing and tuning algorithms that convert visual imagery to stimulation signals, and the entire system had to be incorporated within hermetically sealed packaging that allowed the electronics to operate in the vitreous fluid of the eye indefinitely. Finally, the research team had to develop new surgical techniques in order to integrate the device with the body, ensuring accurate placement of the stimulation electrodes on the retina.

“The artificial retina is a great engineering challenge under the interdisciplinary constraint of biology, enabling technology, regulatory compliance, as well as sophisticated design science,” adds Liu. [Wentai Liu of the University of California, Los Angeles] “The artificial retina provides an interface between biotic and abiotic systems. Its unique design characteristics rely on system-level optimization, rather than the more common practice of component optimization, to achieve miniaturization and integration. Using the most advanced semiconductor technology, the engine for the artificial retina is a ‘system on a chip’ of mixed voltages and mixed analog-digital design, which provides self-contained power and data management and other functionality. This design for the artificial retina facilitates both surgical procedures and regulatory compliance.”

The Argus II design consists of an external video camera system matched to the implanted retinal stimulator, which contains a microelectrode array that spans 20 degrees of visual field. [emphasis mine] …

“The external camera system-built into a pair of glasses-streams video to a belt-worn computer, which converts the video into stimulus commands for the implant,” says Weiland [USC researcher Jim Weiland], “The belt-worn computer encodes the commands into a wireless signal that is transmitted to the implant, which has the necessary electronics to receive and decode both wireless power and data. Based on those data, the implant stimulates the retina with small electrical pulses. The electronics are hermetically packaged and the electrical stimulus is delivered to the retina via a microelectrode array.”

You can see some footage of people using artificial retinas in the context of Grégoire Cosendai’s TEDx Vienna presentation. As I noted in my Aug. 18, 2011 posting where this talk and developments in human enhancement are mentioned, the relevant material can be seen at approximately 13 mins., 25 secs. in Cosendai’s talk.

Second Sight Medical Devices can be found here.