As so often happens in the sciences, now that the initial euphoria has expended itself problems (and solutions) with CRISPR ((clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats))-CAAS9 are being disclosed to those of us who are not experts. From an Oct. 3, 2017 article by Bob Yirka for phys.org,

A team of researchers from the University of California and the University of Tokyo has found a way to use the CRISPR gene editing technique that does not rely on a virus for delivery. In their paper published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering, the group describes the new technique, how well it works and improvements that need to be made to make it a viable gene editing tool.

CRISPR-Cas9 has been in the news a lot lately because it allows researchers to directly edit genes—either disabling unwanted parts or replacing them altogether. But despite many success stories, the technique still suffers from a major deficit that prevents it from being used as a true medical tool—it sometimes makes mistakes. Those mistakes can cause small or big problems for a host depending on what goes wrong. Prior research has suggested that the majority of mistakes are due to delivery problems, which means that a replacement for the virus part of the technique is required. In this new effort, the researchers report that they have discovered just a such a replacement, and it worked so well that it was able to repair a gene mutation in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy mouse model. The team has named the new technique CRISPR-Gold, because a gold nanoparticle was used to deliver the gene editing molecules instead of a virus.

An Oct. 2, 2017 article by Abby Olena for The Scientist lays out the CRISPR-CAS9 problems the scientists are trying to solve (Note: Links have been removed),

While promising, applications of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing have so far been limited by the challenges of delivery—namely, how to get all the CRISPR parts to every cell that needs them. In a study published today (October 2) in Nature Biomedical Engineering, researchers have successfully repaired a mutation in the gene for dystrophin in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy by injecting a vehicle they call CRISPR-Gold, which contains the Cas9 protein, guide RNA, and donor DNA, all wrapped around a tiny gold ball.

The authors have made “great progress in the gene editing area,” says Tufts University biomedical engineer Qiaobing Xu, who did not participate in the work but penned an accompanying commentary. Because their approach is nonviral, Xu explains, it will minimize the potential off-target effects that result from constant Cas9 activity, which occurs when users deliver the Cas9 template with a viral vector.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a degenerative disease of the muscles caused by a lack of the protein dystrophin. In about a third of patients, the gene for dystrophin has small deletions or single base mutations that render it nonfunctional, which makes this gene an excellent candidate for gene editing. Researchers have previously used viral delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components to delete the mutated exon and achieve clinical improvements in mouse models of the disease.

…

“In this paper, we were actually able to correct [the gene for] dystrophin back to the wild-type sequence” via homology-directed repair (HDR), coauthor Niren Murthy, a drug delivery researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, tells The Scientist. “The other way of treating this is to do something called exon skipping, which is where you delete some of the exons and you can get dystrophin to be produced, but it’s not [as functional as] the wild-type protein.”

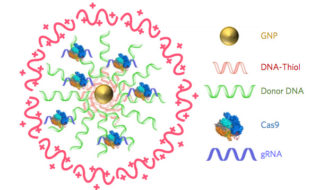

The research team created CRISPR-Gold by covering a central gold nanoparticle with DNA that they modified so it would stick to the particle. This gold-conjugated DNA bound the donor DNA needed for HDR, which the Cas9 protein and guide RNA bound to in turn. They coated the entire complex with a polymer that seems to trigger endocytosis and then facilitate escape of the Cas9 protein, guide RNA, and template DNA from endosomes within cells.

In order to do HDR, “you have to provide the cell [with] the Cas9 enzyme, guide RNA by which you target Cas9 to a particular part of the genome, and a big chunk of DNA, which will be used as a template to edit the mutant sequence to wild-type,” explains coauthor Irina Conboy, who studies tissue repair at the University of California, Berkeley. “They all have to be present at the same time and at the same place, so in our system you have a nanoparticle which simultaneously delivers all of those three key components in their active state.”

…

Olena’s article carries on to describe how the team created CRISPR-Gold and more.

Additional technical details are available in an Oct. 3, 2017 University of California at Berkeley news release by Brett Israel (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item (Note: A link has been removed) ,

Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, have engineered a new way to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology inside cells and have demonstrated in mice that the technology can repair the mutation that causes Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a severe muscle-wasting disease. A new study shows that a single injection of CRISPR-Gold, as the new delivery system is called, into mice with Duchenne muscular dystrophy led to an 18-times-higher correction rate and a two-fold increase in a strength and agility test compared to control groups.

CRISPR–Gold is composed of 15 nanometer gold nanoparticles that are conjugated to thiol-modified oligonucleotides (DNA-Thiol), which are hybridized with single-stranded donor DNA and subsequently complexed with Cas9 and encapsulated by a polymer that disrupts the endosome of the cell.

Since 2012, when study co-author Jennifer Doudna, a professor of molecular and cell biology and of chemistry at UC Berkeley, and colleague Emmanuelle Charpentier, of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, repurposed the Cas9 protein to create a cheap, precise and easy-to-use gene editor, researchers have hoped that therapies based on CRISPR-Cas9 would one day revolutionize the treatment of genetic diseases. Yet developing treatments for genetic diseases remains a big challenge in medicine. This is because most genetic diseases can be cured only if the disease-causing gene mutation is corrected back to the normal sequence, and this is impossible to do with conventional therapeutics.

CRISPR/Cas9, however, can correct gene mutations by cutting the mutated DNA and triggering homology-directed DNA repair. However, strategies for safely delivering the necessary components (Cas9, guide RNA that directs Cas9 to a specific gene, and donor DNA) into cells need to be developed before the potential of CRISPR-Cas9-based therapeutics can be realized. A common technique to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 into cells employs viruses, but that technique has a number of complications. CRISPR-Gold does not need viruses.

In the new study, research lead by the laboratories of Berkeley bioengineering professors Niren Murthy and Irina Conboy demonstrated that their novel approach, called CRISPR-Gold because gold nanoparticles are a key component, can deliver Cas9 – the protein that binds and cuts DNA – along with guide RNA and donor DNA into the cells of a living organism to fix a gene mutation.

“CRISPR-Gold is the first example of a delivery vehicle that can deliver all of the CRISPR components needed to correct gene mutations, without the use of viruses,” Murthy said.

The study was published October 2 [2017] in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

CRISPR-Gold repairs DNA mutations through a process called homology-directed repair. Scientists have struggled to develop homology-directed repair-based therapeutics because they require activity at the same place and time as Cas9 protein, an RNA guide that recognizes the mutation and donor DNA to correct the mutation.

To overcome these challenges, the Berkeley scientists invented a delivery vessel that binds all of these components together, and then releases them when the vessel is inside a wide variety of cell types, triggering homology directed repair. CRISPR-Gold’s gold nanoparticles coat the donor DNA and also bind Cas9. When injected into mice, their cells recognize a marker in CRISPR-Gold and then import the delivery vessel. Then, through a series of cellular mechanisms, CRISPR-Gold is released into the cells’ cytoplasm and breaks apart, rapidly releasing Cas9 and donor DNA.

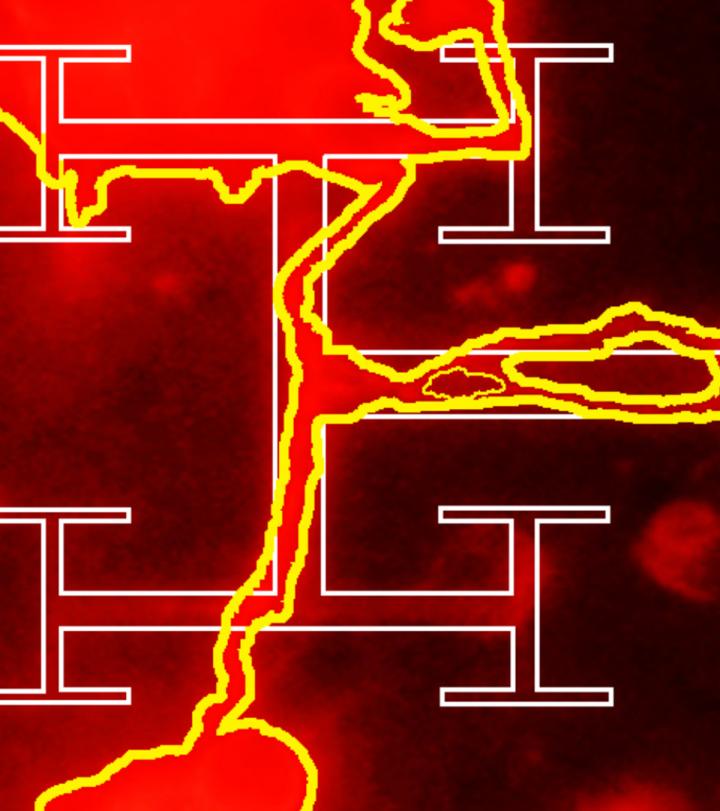

A single injection of CRISPR-Gold into muscle tissue of mice that model Duchenne muscular dystrophy restored 5.4 percent of the dystrophin gene, which causes the disease, to the wild- type, or normal, sequence. This correction rate was approximately 18 times higher than in mice treated with Cas9 and donor DNA by themselves, which experienced only a 0.3 percent correction rate.

Importantly, the study authors note, CRISPR-Gold faithfully restored the normal sequence of dystrophin, which is a significant improvement over previously published approaches that only removed the faulty part of the gene, making it shorter and converting one disease into another, milder disease.

CRISPR-Gold was also able to reduce tissue fibrosis – the hallmark of diseases where muscles do not function properly – and enhanced strength and agility in mice with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. CRISPR-Gold-treated mice showed a two-fold increase in hanging time in a common test for mouse strength and agility, compared to mice injected with a control.

“These experiments suggest that it will be possible to develop non-viral CRISPR therapeutics that can safely correct gene mutations, via the process of homology-directed repair, by simply developing nanoparticles that can simultaneously encapsulate all of the CRISPR components,” Murthy said.

The study found that CRISPR-Gold’s approach to Cas9 protein delivery is safer than viral delivery of CRISPR, which, in addition to toxicity, amplifies the side effects of Cas9 through continuous expression of this DNA-cutting enzyme. When the research team tested CRISPR-Gold’s gene-editing capability in mice, they found that CRISPR-Gold efficiently corrected the DNA mutation that causes Duchenne muscular dystrophy, with minimal collateral DNA damage.

The researchers quantified CRISPR-Gold’s off-target DNA damage and found damage levels similar to the that of a typical DNA sequencing error in a typical cell that was not exposed to CRISPR (0.005 – 0.2 percent). To test for possible immunogenicity, the blood stream cytokine profiles of mice were analyzed at 24 hours and two weeks after the CRISPR-Gold injection. CRISPR-Gold did not cause an acute up-regulation of inflammatory cytokines in plasma, after multiple injections, or weight loss, suggesting that CRISPR-Gold can be used multiple times safely, and that it has a high therapeutic window for gene editing in muscle tissue.

“CRISPR-Gold and, more broadly, CRISPR-nanoparticles open a new way for safer, accurately controlled delivery of gene-editing tools,” Conboy said. “Ultimately, these techniques could be developed into a new medicine for Duchenne muscular dystrophy and a number of other genetic diseases.”

A clinical trial will be needed to discern whether CRISPR-Gold is an effective treatment for genetic diseases in humans. Study co-authors Kunwoo Lee and Hyo Min Park have formed a start-up company, GenEdit (Murthy has an ownership stake in GenEdit), which is focused on translating the CRISPR-Gold technology into humans. The labs of Murthy and Conboy are also working on the next generation of particles that can deliver CRISPR into tissues from the blood stream and would preferentially target adult stem cells, which are considered the best targets for gene correction because stem and progenitor cells are capable of gene editing, self-renewal and differentiation.

“Genetic diseases cause devastating levels of mortality and morbidity, and new strategies for treating them are greatly needed,” Murthy said. “CRISPR-Gold was able to correct disease-causing gene mutations in vivo, via the non-viral delivery of Cas9 protein, guide RNA and donor DNA, and therefore has the potential to develop into a therapeutic for treating genetic diseases.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the W.M. Keck Foundation, the Moore Foundation, the Li Ka Shing Foundation, Calico, Packer, Roger’s and SENS, and the Center of Innovation (COI) Program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nanoparticle delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein and donor DNA in vivo induces homology-directed DNA repair by Kunwoo Lee, Michael Conboy, Hyo Min Park, Fuguo Jiang, Hyun Jin Kim, Mark A. Dewitt, Vanessa A. Mackley, Kevin Chang, Anirudh Rao, Colin Skinner, Tamanna Shobha, Melod Mehdipour, Hui Liu, Wen-chin Huang, Freeman Lan, Nicolas L. Bray, Song Li, Jacob E. Corn, Kazunori Kataoka, Jennifer A. Doudna, Irina Conboy, & Niren Murthy. Nature Biomedical Engineering (2017) doi:10.1038/s41551-017-0137-2 Published online: 02 October 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.