‘Nanotraps’ are not vaccines although they do call the immune system into play. They represent a different way for dealing with COVID-19. (This work reminds of my June 24, 2020 posting Tiny sponges lure coronavirus away from lung cells where the researchers have a similar approach with what they call ‘nanosponges’.)

An April 27, 2021 news item on Nanowerk makes the announcement,

Researchers at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) at the University of Chicago have designed a completely novel potential treatment for COVID-19: nanoparticles that capture SARS-CoV-2 viruses within the body and then use the body’s own immune system to destroy it.

These “Nanotraps” attract the virus by mimicking the target cells the virus infects. When the virus binds to the Nanotraps, the traps then sequester the virus from other cells and target it for destruction by the immune system.

In theory, these Nanotraps could also be used on variants of the virus, leading to a potential new way to inhibit the virus going forward. Though the therapy remains in early stages of testing, the researchers envision it could be administered via a nasal spray as a treatment for COVID-19.

…

An April 27, 2021 University of Chicago news release (also on EurekAlert) by Emily Ayshford, which originated the news item, describes the work in more detail,

“Since the pandemic began, our research team has been developing this new way to treat COVID-19,” said Asst. Prof. Jun Huang, whose lab led the research. “We have done rigorous testing to prove that these Nanotraps work, and we are excited about their potential.”

Designing the perfect trap

To design the Nanotrap, the research team – led by postdoctoral scholar Min Chen and graduate student Jill Rosenberg – looked into the mechanism SARS-CoV-2 uses to bind to cells: a spike-like protein on its surface that binds to a human cell’s ACE2 receptor protein.

To create a trap that would bind to the virus in the same way, they designed nanoparticles with a high density of ACE2 proteins on their surface. Similarly, they designed other nanoparticles with neutralizing antibodies on their surfaces. (These antibodies are created inside the body when someone is infected and are designed to latch onto the coronavirus in various ways).

Both ACE2 proteins and neutralizing antibodies have been used in treatments for COVID-19, but by attaching them to nanoparticles, the researchers created an even more robust system for trapping and eliminating the virus.

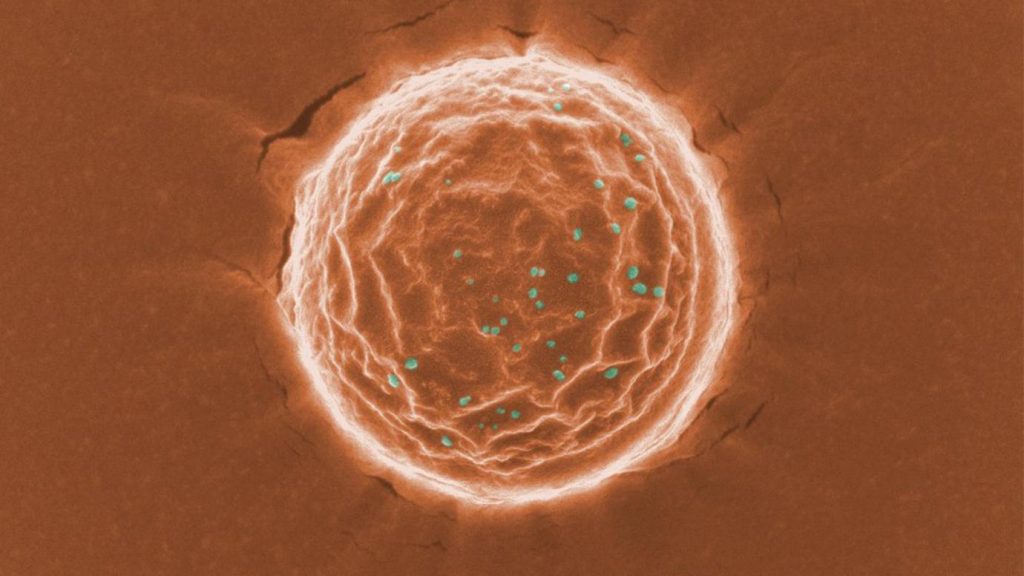

Made of FDA [US Food and Drug Administration]-approved polymers and phospholipids, the nanoparticles are about 500 nanometers in diameter – much smaller than a cell. That means the Nanotraps can reach more areas inside the body and more effectively trap the virus.

The researchers tested the safety of the system in a mouse model and found no toxicity. They then tested the Nanotraps against a pseudovirus – a less potent model of a virus that doesn’t replicate – in human lung cells in tissue culture plates and found that they completely blocked entry into the cells.

Once the pseudovirus bound itself to the nanoparticle – which in tests took about 10 minutes after injection – the nanoparticles used a molecule that calls the body’s macrophages to engulf and degrade the Nanotrap. Macrophages will generally eat nanoparticles within the body, but the Nanotrap molecule speeds up the process. The nanoparticles were cleared and degraded within 48 hours.

The researchers also tested the nanoparticles with a pseudovirus in an ex vivo lung perfusion system – a pair of donated lungs that is kept alive with a ventilator – and found that they completely blocked infection in the lungs.

They also collaborated with researchers at Argonne National Laboratory to test the Nanotraps with a live virus (rather than a pseudovirus) in an in vitro system. They found that their system inhibited the virus 10 times better than neutralizing antibodies or soluble ACE2 alone.

A potential future treatment for COVID-19 and beyond

Next the researchers hope to further test the system, including more tests with a live virus and on the many virus variants.

“That’s what is so powerful about this Nanotrap,” Rosenberg said. “It’s easily modulated. We can switch out different antibodies or proteins or target different immune cells, based on what we need with new variants.”

The Nanotraps can be stored in a standard freezer and could ultimately be given via an intranasal spray, which would place them directly in the respiratory system and make them most effective.

The researchers say it is also possible to serve as a vaccine by optimizing the Nanotrap formulation, creating an ultimate therapeutic system for the virus.

“This is the starting point,” Huang said. “We want to do something to help the world.”

The research involved collaborators across departments, including chemistry, biology, and medicine.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nanotraps for the containment and clearance of SARS-CoV-2 by Min Chen, Jillian Rosenberg, Xiaolei Cai, Andy Chao Hsuan Lee, Jiuyun Shi, Mindy Nguyen, Thirushan Wignakumar, Vikranth Mirle, Arianna Joy Edobor, John Fung, Jessica Scott Donington, Kumaran Shanmugarajah, Yiliang Lin, Eugene Chang, Glenn Randall, Pablo Penaloza-MacMaster, Bozhi Tian, Maria Lucia Madariaga, Jun Huang. Matter, April 19, 2021, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matt.2021.04.005

This paper appears to be open access.