This is exciting provided they can scale up the metamaterial for industrial use. A Feb. 9, 2017 news item on Nanowerk announces a new metamaterial that could change air conditioning from the University of Colorado at Boulder (Note: A link has been removed),

A team of University of Colorado Boulder engineers has developed a scalable manufactured metamaterial — an engineered material with extraordinary properties not found in nature — to act as a kind of air conditioning system for structures. It has the ability to cool objects even under direct sunlight with zero energy and water consumption.

When applied to a surface, the metamaterial film cools the object underneath by efficiently reflecting incoming solar energy back into space while simultaneously allowing the surface to shed its own heat in the form of infrared thermal radiation.

The new material, which is described today in the journal Science (“Scalable-manufactured randomized glass-polymer hybrid metamaterial for daytime radiative cooling”), could provide an eco-friendly means of supplementary cooling for thermoelectric power plants, which currently require large amounts of water and electricity to maintain the operating temperatures of their machinery.

A Feb. 9, 2017 University of Colorado at Boulder news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, expands on the theme (Note: Links have been removed),

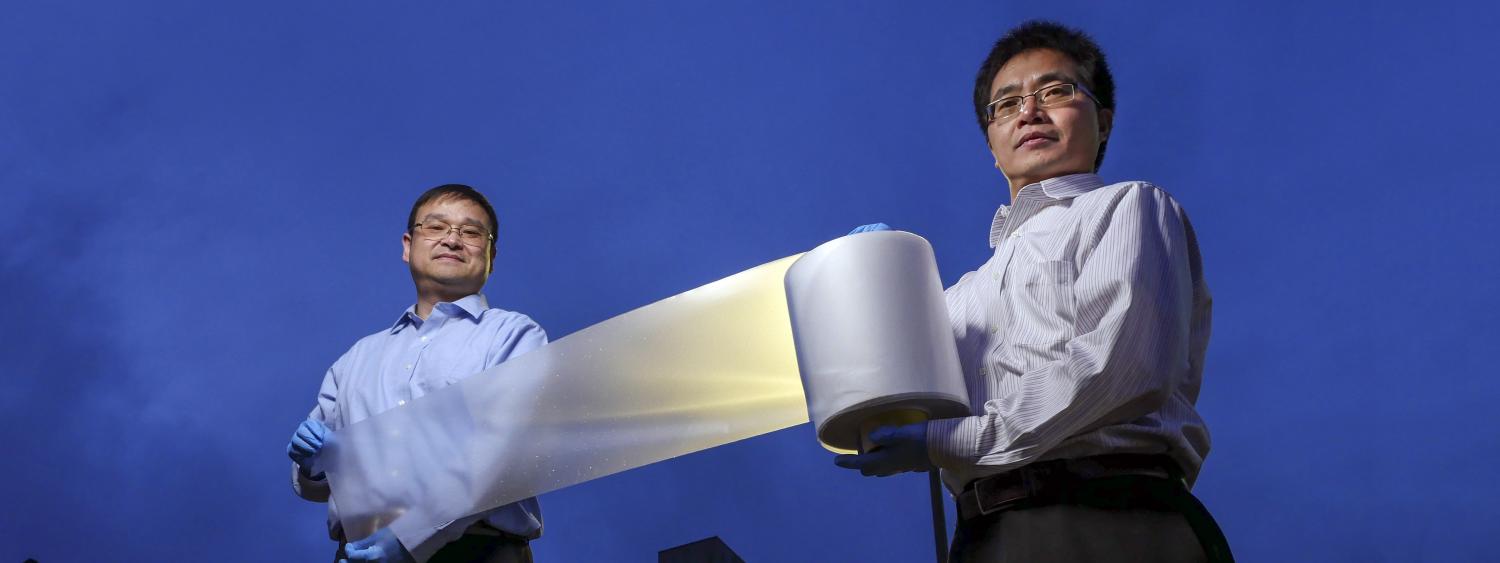

The researchers’ glass-polymer hybrid material measures just 50 micrometers thick — slightly thicker than the aluminum foil found in a kitchen — and can be manufactured economically on rolls, making it a potentially viable large-scale technology for both residential and commercial applications.

“We feel that this low-cost manufacturing process will be transformative for real-world applications of this radiative cooling technology,” said Xiaobo Yin, co-director of the research and an assistant professor who holds dual appointments in CU Boulder’s Department of Mechanical Engineering and the Materials Science and Engineering Program. Yin received DARPA’s [US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency] Young Faculty Award in 2015.

The material takes advantage of passive radiative cooling, the process by which objects naturally shed heat in the form of infrared radiation, without consuming energy. Thermal radiation provides some natural nighttime cooling and is used for residential cooling in some areas, but daytime cooling has historically been more of a challenge. For a structure exposed to sunlight, even a small amount of directly-absorbed solar energy is enough to negate passive radiation.

The challenge for the CU Boulder researchers, then, was to create a material that could provide a one-two punch: reflect any incoming solar rays back into the atmosphere while still providing a means of escape for infrared radiation. To solve this, the researchers embedded visibly-scattering but infrared-radiant glass microspheres into a polymer film. They then added a thin silver coating underneath in order to achieve maximum spectral reflectance.

“Both the glass-polymer metamaterial formation and the silver coating are manufactured at scale on roll-to-roll processes,” added Ronggui Yang, also a professor of mechanical engineering and a Fellow of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

“Just 10 to 20 square meters of this material on the rooftop could nicely cool down a single-family house in summer,” said Gang Tan, an associate professor in the University of Wyoming’s Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering and a co-author of the paper.

In addition to being useful for cooling of buildings and power plants, the material could also help improve the efficiency and lifetime of solar panels. In direct sunlight, panels can overheat to temperatures that hamper their ability to convert solar rays into electricity.

“Just by applying this material to the surface of a solar panel, we can cool the panel and recover an additional one to two percent of solar efficiency,” said Yin. “That makes a big difference at scale.”

The engineers have applied for a patent for the technology and are working with CU Boulder’s Technology Transfer Office to explore potential commercial applications. They plan to create a 200-square-meter “cooling farm” prototype in Boulder in 2017.

The invention is the result of a $3 million grant awarded in 2015 to Yang, Yin and Tang by the Energy Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E).

“The key advantage of this technology is that it works 24/7 with no electricity or water usage,” said Yang “We’re excited about the opportunity to explore potential uses in the power industry, aerospace, agriculture and more.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Scalable-manufactured randomized glass-polymer hybrid metamaterial for daytime radiative cooling by Yao Zhai, Yaoguang Ma, Sabrina N. David, Dongliang Zhao, Runnan Lou, Gang Tan, Ronggui Yang, Xiaobo Yin. Science 09 Feb 2017: DOI: 10.1126/science.aai7899

This paper is behind a paywall.

Members of the research team show off the metamaterial (?) Courtesy: University of Colorado at Boulder

I added the caption to this image, which was on the University of Colorado at Boulder’s home page where it accompanied the news release headline on the rotating banner.