A March 23, 2023 news item on ScienceDaily announces a neural implant that addresses failures due to scarring issues,

Researchers have developed a new type of neural implant that could restore limb function to amputees and others who have lost the use of their arms or legs.

In a study carried out in rats, researchers from the University of Cambridge used the device to improve the connection between the brain and paralysed limbs. The device combines flexible electronics and human stem cells — the body’s ‘reprogrammable’ master cells — to better integrate with the nerve and drive limb function.

Previous attempts at using neural implants to restore limb function have mostly failed, as scar tissue tends to form around the electrodes over time, impeding the connection between the device and the nerve. By sandwiching a layer of muscle cells reprogrammed from stem cells between the electrodes and the living tissue, the researchers found that the device integrated with the host’s body and the formation of scar tissue was prevented. The cells survived on the electrode for the duration of the 28-day experiment, the first time this has been monitored over such a long period.

…

A March 22, 2023 University of Cambridge press release (also on EurekAlert but published March 23, 2023) by Sarah Collins, delves further into the topic,

The researchers say that by combining two advanced therapies for nerve regeneration – cell therapy and bioelectronics – into a single device, they can overcome the shortcomings of both approaches, improving functionality and sensitivity.

While extensive research and testing will be needed before it can be used in humans, the device is a promising development for amputees or those who have lost function of a limb or limbs. The results are reported in the journal Science Advances.

A huge challenge when attempting to reverse injuries that result in the loss of a limb or the loss of function of a limb is the inability of neurons to regenerate and rebuild disrupted neural circuits.

“If someone has an arm or a leg amputated, for example, all the signals in the nervous system are still there, even though the physical limb is gone,” said Dr Damiano Barone from Cambridge’s Department of Clinical Neurosciences, who co-led the research. “The challenge with integrating artificial limbs, or restoring function to arms or legs, is extracting the information from the nerve and getting it to the limb so that function is restored.”

One way of addressing this problem is implanting a nerve in the large muscles of the shoulder and attaching electrodes to it. The problem with this approach is scar tissue forms around the electrode, plus it is only possible to extract surface-level information from the electrode.

To get better resolution, any implant for restoring function would need to extract much more information from the electrodes. And to improve sensitivity, the researchers wanted to design something that could work on the scale of a single nerve fibre, or axon.

“An axon itself has a tiny voltage,” said Barone. “But once it connects with a muscle cell, which has a much higher voltage, the signal from the muscle cell is easier to extract. That’s where you can increase the sensitivity of the implant.”

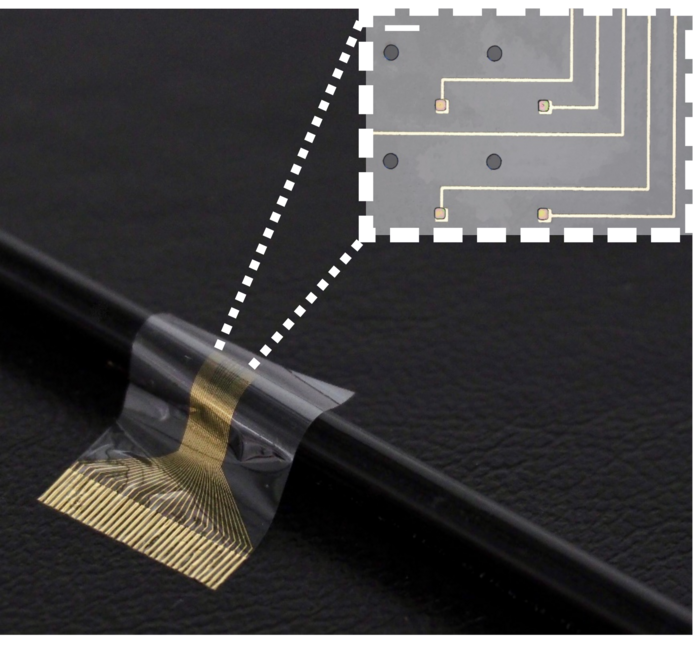

The researchers designed a biocompatible flexible electronic device that is thin enough to be attached to the end of a nerve. A layer of stem cells, reprogrammed into muscle cells, was then placed on the electrode. This is the first time that this type of stem cell, called an induced pluripotent stem cell, has been used in a living organism in this way.

“These cells give us an enormous degree of control,” said Barone. “We can tell them how to behave and check on them throughout the experiment. By putting cells in between the electronics and the living body, the body doesn’t see the electrodes, it just sees the cells, so scar tissue isn’t generated.”

The Cambridge biohybrid device was implanted into the paralysed forearm of the rats. The stem cells, which had been transformed into muscle cells prior to implantation, integrated with the nerves in the rat’s forearm. While the rats did not have movement restored to their forearms, the device was able to pick up the signals from the brain that control movement. If connected to the rest of the nerve or a prosthetic limb, the device could help restore movement.

The cell layer also improved the function of the device, by improving resolution and allowing long-term monitoring inside a living organism. The cells survived through the 28-day experiment: the first time that cells have been shown to survive an extended experiment of this kind.

The researchers say that their approach has multiple advantages over other attempts to restore function in amputees. In addition to its easier integration and long-term stability, the device is small enough that its implantation would only require keyhole surgery. Other neural interfacing technologies for the restoration of function in amputees require complex patient-specific interpretations of cortical activity to be associated with muscle movements, while the Cambridge-developed device is a highly scalable solution since it uses ‘off the shelf’ cells.

In addition to its potential for the restoration of function in people who have lost the use of a limb or limbs, the researchers say their device could also be used to control prosthetic limbs by interacting with specific axons responsible for motor control.

“This interface could revolutionise the way we interact with technology,” said co-first author Amy Rochford, from the Department of Engineering. “By combining living human cells with bioelectronic materials, we’ve created a system that can communicate with the brain in a more natural and intuitive way, opening up new possibilities for prosthetics, brain-machine interfaces, and even enhancing cognitive abilities.”

“This technology represents an exciting new approach to neural implants, which we hope will unlock new treatments for patients in need,” said co-first author Dr Alejandro Carnicer-Lombarte, also from the Department of Engineering.

“This was a high-risk endeavour, and I’m so pleased that it worked,” said Professor George Malliaras from Cambridge’s Department of Engineering, who co-led the research. “It’s one of those things that you don’t know whether it will take two years or ten before it works, and it ended up happening very efficiently.”

The researchers are now working to further optimise the devices and improve their scalability. The team have filed a patent application on the technology with the support of Cambridge Enterprise, the University’s technology transfer arm.

The technology relies on opti-oxTM enabled muscle cells. opti-ox is a precision cellular reprogramming technology that enables faithful execution of genetic programmes in cells allowing them to be manufactured consistently at scale. The opti-ox enabled muscle iPSC cell lines used in the experiment were supplied by the Kotter lab [Mark Kotter] from the University of Cambridge. The opti-ox reprogramming technology is owned by synthetic biology company bit.bio.

The research was supported in part by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), Wellcome, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Functional neurological restoration of amputated peripheral nerve using biohybrid regenerative bioelectronics by Amy E. Rochford, Alejandro Carnicer-Lombarte, Malak Kawan, Amy Jin, Sam Hilton, Vincenzo F. Curto, Alexandra L. Rutz, Thomas Moreau, Mark R. N. Kotter, George G. Malliaras, and Damiano G. Barone. Science Advances 22 Mar 2023 Vol 9, Issue 12 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.add8162

This paper is open access.

The synthetic biology company mentioned in the press release, bit.bio is here