There was a big splash a few weeks ago when it was announced that Neuralink’s (Elon Musk company) brain implant had been surgically inserted into its first human patient.

Getting approval

David Tuffley, senior lecturer in Applied Ethics & CyberSecurity at Griffith University (Australia), provides a good overview of the road Neuralink took to getting FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) approval for human clinical trials in his May 29, 2023 essay for The Conversation, Note: Links have been removed,

Since its founding in 2016, Elon Musk’s neurotechnology company Neuralink has had the ambitious mission to build a next-generation brain implant with at least 100 times more brain connections than devices currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The company has now reached a significant milestone, having received FDA approval to begin human trials. So what were the issues keeping the technology in the pre-clinical trial phase for as long as it was? And have these concerns been addressed?

…

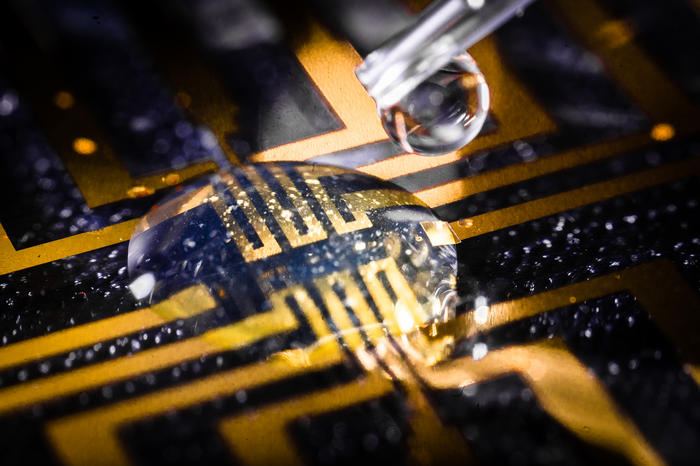

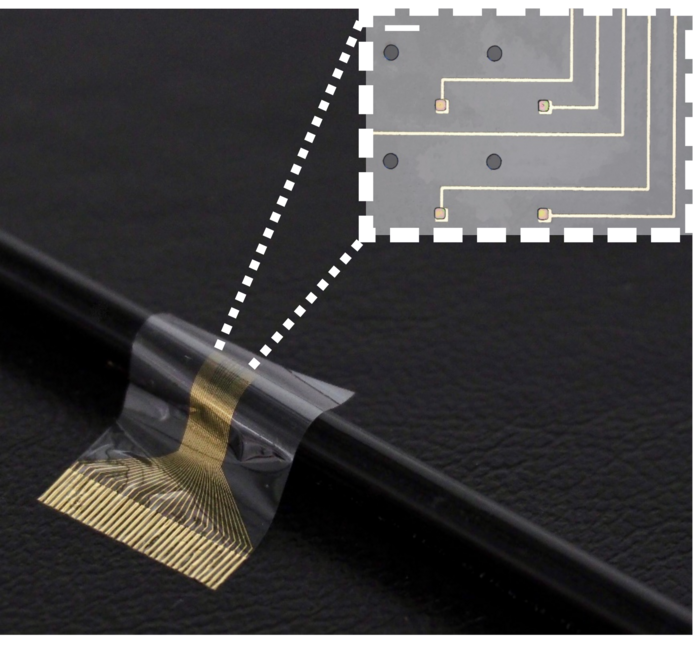

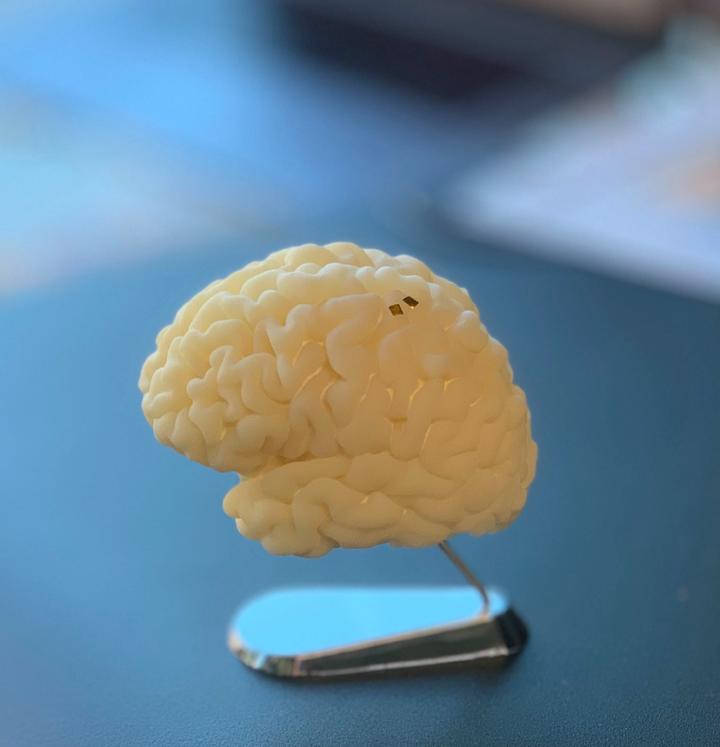

Neuralink is making a Class III medical device known as a brain-computer interface (BCI). The device connects the brain to an external computer via a Bluetooth signal, enabling continuous communication back and forth.

The device itself is a coin-sized unit called a Link. It’s implanted within a small disk-shaped cutout in the skull using a precision surgical robot. The robot splices a thousand tiny threads from the Link to certain neurons in the brain. [emphasis mine] Each thread is about a quarter the diameter of a human hair.

…

The company says the device could enable precise control of prosthetic limbs, giving amputees natural motor skills. It could revolutionise treatment for conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy and spinal cord injuries. It also shows some promise for potential treatment of obesity, autism, depression, schizophrenia and tinnitus.

Several other neurotechnology companies and researchers have already developed BCI technologies that have helped people with limited mobility regain movement and complete daily tasks.

…

In February 2021, Musk said Neuralink was working with the FDA to secure permission to start initial human trials later that year. But human trials didn’t commence in 2021.

Then, in March 2022, Neuralink made a further application to the FDA to establish its readiness to begin humans trials.

One year and three months later, on May 25 2023, Neuralink finally received FDA approval for its first human clinical trial. Given how hard Neuralink has pushed for permission to begin, we can assume it will begin very soon. [emphasis mine]

The approval has come less than six months after the US Office of the Inspector General launched an investigation into Neuralink over potential animal welfare violations. [emphasis mine]

…

In accessible language, Tuffley goes on to discuss the FDA’s specific technical issues with implants and how they were addressed in his May 29, 2023 essay.

More about how Neuralink’s implant works and some concerns

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) journalist Andrew Chang offers an almost 13 minute video, “Neuralink brain chip’s first human patient. How does it work?” Chang is a little overenthused for my taste but he offers some good information about neural implants, along with informative graphics in his presentation.

So, Tuffley was right about Neuralink getting ready quickly for human clinical trials as you can guess from the title of Chang’s CBC video.

Jennifer Korn announced that recruitment had started in her September 20, 2023 article for CNN (Cable News Network), Note: Links have been removed,

Elon Musk’s controversial biotechnology startup Neuralink opened up recruitment for its first human clinical trial Tuesday, according to a company blog.

After receiving approval from an independent review board, Neuralink is set to begin offering brain implants to paralysis patients as part of the PRIME Study, the company said. PRIME, short for Precise Robotically Implanted Brain-Computer Interface, is being carried out to evaluate both the safety and functionality of the implant.

Trial patients will have a chip surgically placed in the part of the brain that controls the intention to move. The chip, installed by a robot, will then record and send brain signals to an app, with the initial goal being “to grant people the ability to control a computer cursor or keyboard using their thoughts alone,” the company wrote.

Those with quadriplegia [sometimes known as tetraplegia] due to cervical spinal cord injury or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) may qualify for the six-year-long study – 18 months of at-home and clinic visits followed by follow-up visits over five years. Interested people can sign up in the patient registry on Neuralink’s website.

Musk has been working on Neuralink’s goal of using implants to connect the human brain to a computer for five years, but the company so far has only tested on animals. The company also faced scrutiny after a monkey died in project testing in 2022 as part of efforts to get the animal to play Pong, one of the first video games.

…

I mentioned three Reuters investigative journalists who were reporting on Neuralink’s animal abuse allegations (emphasized in Tuffley’s essay) in a July 7, 2023 posting, “Global dialogue on the ethics of neurotechnology on July 13, 2023 led by UNESCO.” Later that year, Neuralink was cleared by the US Department of Agriculture (see September 24,, 2023 article by Mahnoor Jehangir for BNN Breaking).

Plus, Neuralink was being investigated over more allegations according to a February 9, 2023 article by Rachel Levy for Reuters, this time regarding hazardous pathogens,

The U.S. Department of Transportation said on Thursday it is investigating Elon Musk’s brain-implant company Neuralink over the potentially illegal movement of hazardous pathogens.

A Department of Transportation spokesperson told Reuters about the probe after the Physicians Committee of Responsible Medicine (PCRM), an animal-welfare advocacy group,wrote to Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, opens new tab earlier on Thursday to alert it of records it obtained on the matter.

PCRM said it obtained emails and other documents that suggest unsafe packaging and movement of implants removed from the brains of monkeys. These implants may have carried infectious diseases in violation of federal law, PCRM said.

…

There’s an update about the hazardous materials in the next section. Spoiler alert, the company got fined.

Neuralink’s first human implant

A January 30, 2024 article (Associated Press with files from Reuters) on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC) online news webspace heralded the latest about Neurlink’s human clinical trials,

The first human patient received an implant from Elon Musk’s computer-brain interface company Neuralink over the weekend, the billionaire says.

In a post Monday [January 29, 2024] on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, Musk said that the patient received the implant the day prior and was “recovering well.” He added that “initial results show promising neuron spike detection.”

Spikes are activity by neurons, which the National Institutes of Health describe as cells that use electrical and chemical signals to send information around the brain and to the body.

The billionaire, who owns X and co-founded Neuralink, did not provide additional details about the patient.

…

When Neuralink announced in September [2023] that it would begin recruiting people, the company said it was searching for individuals with quadriplegia due to cervical spinal cord injury or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, commonly known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

…

Neuralink reposted Musk’s Monday [January 29, 2024] post on X, but did not publish any additional statements acknowledging the human implant. The company did not immediately respond to requests for comment from The Associated Press or Reuters on Tuesday [January 30, 2024].

…

In a separate Monday [January 29, 2024] post on X, Musk said that the first Neuralink product is called “Telepathy” — which, he said, will enable users to control their phones or computers “just by thinking.” He said initial users would be those who have lost use of their limbs.

The startup’s PRIME Study is a trial for its wireless brain-computer interface to evaluate the safety of the implant and surgical robot.

…

Now for the hazardous materials, January 30, 2024 article, Note: A link has been removed,

…

Earlier this month [January 2024], a Reuters investigation found that Neuralink was fined for violating U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) rules regarding the movement of hazardous materials. During inspections of the company’s facilities in Texas and California in February 2023, DOT investigators found the company had failed to register itself as a transporter of hazardous material.

They also found improper packaging of hazardous waste, including the flammable liquid Xylene. Xylene can cause headaches, dizziness, confusion, loss of muscle co-ordination and even death, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

…

The records do not say why Neuralink would need to transport hazardous materials or whether any harm resulted from the violations.

Skeptical thoughts about Elon Musk and Neuralink

Earlier this month (February 2024), the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) published an article by health reporters, Jim Reed and Joe McFadden, that highlights the history of brain implants, the possibilities, and notes some of Elon Musk’s more outrageous claims for Neuralink’s brain implants,

Elon Musk is no stranger to bold claims – from his plans to colonise Mars to his dreams of building transport links underneath our biggest cities. This week the world’s richest man said his Neuralink division had successfully implanted its first wireless brain chip into a human.

Is he right when he says this technology could – in the long term – save the human race itself?

Sticking electrodes into brain tissue is really nothing new.

In the 1960s and 70s electrical stimulation was used to trigger or suppress aggressive behaviour in cats. By the early 2000s monkeys were being trained to move a cursor around a computer screen using just their thoughts.

“It’s nothing novel, but implantable technology takes a long time to mature, and reach a stage where companies have all the pieces of the puzzle, and can really start to put them together,” says Anne Vanhoestenberghe, professor of active implantable medical devices, at King’s College London.

Neuralink is one of a growing number of companies and university departments attempting to refine and ultimately commercialise this technology. The focus, at least to start with, is on paralysis and the treatment of complex neurological conditions.

…

Reed and McFadden’s February 2024 BBC article describes a few of the other brain implant efforts, Note: Links have been removed,

One of its [Neuralink’s] main rivals, a start-up called Synchron backed by funding from investment firms controlled by Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, has already implanted its stent-like device into 10 patients.

Back in December 2021, Philip O’Keefe, a 62-year old Australian who lives with a form of motor neurone disease, composed the first tweet using just his thoughts to control a cursor.

And researchers at Lausanne University in Switzerland have shown it is possible for a paralysed man to walk again by implanting multiple devices to bypass damage caused by a cycling accident.

In a research paper published this year, they demonstrated a signal could be beamed down from a device in his brain to a second device implanted at the base of his spine, which could then trigger his limbs to move.

Some people living with spinal injuries are sceptical about the sudden interest in this new kind of technology.

“These breakthroughs get announced time and time again and don’t seem to be getting any further along,” says Glyn Hayes, who was paralysed in a motorbike accident in 2017, and now runs public affairs for the Spinal Injuries Association.

“If I could have anything back, it wouldn’t be the ability to walk. It would be putting more money into a way of removing nerve pain, for example, or ways to improve bowel, bladder and sexual function.” [emphasis mine]

…

Musk, however, is focused on something far more grand for Neuralink implants, from Reed and McFadden’s February 2024 BBC article, Note: A link has been removed,

But for Elon Musk, “solving” brain and spinal injuries is just the first step for Neuralink.

The longer-term goal is “human/AI symbiosis” [emphasis mine], something he describes as “species-level important”.

…

Musk himself has already talked about a future where his device could allow people to communicate with a phone or computer “faster than a speed typist or auctioneer”.

In the past, he has even said saving and replaying memories may be possible, although he recognised “this is sounding increasingly like a Black Mirror episode.”

One of the experts quoted in Reed and McFadden’s February 2024 BBC article asks a pointed question,

… “At the moment, I’m struggling to see an application that a consumer would benefit from, where they would take the risk of invasive surgery,” says Prof Vanhoestenberghe.

“You’ve got to ask yourself, would you risk brain surgery just to be able to order a pizza on your phone?”

…

Rae Hodge’s February 11, 2024 article about Elon Musk and his hyped up Neuralink implant for Salon is worth reading in its entirety but for those who don’t have the time or need a little persuading, here are a few excerpts, Note 1: This is a warning; Hodge provides more detail about the animal cruelty allegations; Note 2: Links have been removed,

Elon Musk’s controversial brain-computer interface (BCI) tech, Neuralink, has supposedly been implanted in its first recipient — and as much as I want to see progress for treatment of paralysis and neurodegenerative disease, I’m not celebrating. I bet the neuroscientists he reportedly drove out of the company aren’t either, especially not after seeing the gruesome torture of test monkeys and apparent cover-up that paved the way for this moment.

All of which is an ethics horror show on its own. But the timing of Musk’s overhyped implant announcement gives it an additional insulting subtext. Football players are currently in a battle for their lives against concussion-based brain diseases that plague autopsy reports of former NFL players. And Musk’s boast of false hope came just two weeks before living players take the field in the biggest and most brutal game of the year. [2024 Super Bowl LVIII]

ESPN’s Kevin Seifert reports neuro-damage is up this year as “players suffered a total of 52 concussions from the start of training camp to the beginning of the regular season. The combined total of 213 preseason and regular season concussions was 14% higher than 2021 but within range of the three-year average from 2018 to 2020 (203).”

…

I’m a big fan of body-tech: pacemakers, 3D-printed hips and prosthetic limbs that allow you to wear your wedding ring again after 17 years. Same for brain chips. But BCI is the slow-moving front of body-tech development for good reason. The brain is too understudied. Consequences of the wrong move are dire. Overpromising marketable results on profit-driven timelines — on the backs of such a small community of researchers in a relatively new field — would be either idiotic or fiendish.

Brown University’s research in the sector goes back to the 1990s. Since the emergence of a floodgate-opening 2002 study and the first implant in 2004 by med-tech company BrainGate, more promising results have inspired broader investment into careful research. But BrainGate’s clinical trials started back in 2009, and as noted by Business Insider’s Hilary Brueck, are expected to continue until 2038 — with only 15 participants who have devices installed.

Anne Vanhoestenberghe is a professor of active implantable medical devices at King’s College London. In a recent release, she cautioned against the kind of hype peddled by Musk.

“Whilst there are a few other companies already using their devices in humans and the neuroscience community have made remarkable achievements with those devices, the potential benefits are still significantly limited by technology,” she said. “Developing and validating core technology for long term use in humans takes time and we need more investments to ensure we do the work that will underpin the next generation of BCIs.”

…

Neuralink is a metal coin in your head that connects to something as flimsy as an app. And we’ve seen how Elon treats those. We’ve also seen corporate goons steal a veteran’s prosthetic legs — and companies turn brain surgeons and dentists into repo-men by having them yank anti-epilepsy chips out of people’s skulls, and dentures out of their mouths.

“I think we have a chance with Neuralink to restore full-body functionality to someone who has a spinal cord injury,” Musk said at a 2023 tech summit, adding that the chip could possibly “make up for whatever lost capacity somebody has.”

Maybe BCI can. But only in the careful hands of scientists who don’t have Musk squawking “go faster!” over their shoulders. His greedy frustration with the speed of BCI science is telling, as is the animal cruelty it reportedly prompted.

…

There have been other examples of Musk’s grandiosity. Notably, David Lee expressed skepticism about hyperloop in his August 13, 2013 article for BBC news online

Is Elon Musk’s Hyperloop just a pipe dream?

Much like the pun in the headline, the bright idea of transporting people using some kind of vacuum-like tube is neither new nor imaginative.

There was Robert Goddard, considered the “father of modern rocket propulsion”, who claimed in 1909 that his vacuum system could suck passengers from Boston to New York at 1,200mph.

And then there were Soviet plans for an amphibious monorail – mooted in 1934 – in which two long pods would start their journey attached to a metal track before flying off the end and slipping into the water like a two-fingered Kit Kat dropped into some tea.

So ever since inventor and entrepreneur Elon Musk hit the world’s media with his plans for the Hyperloop, a healthy dose of scepticism has been in the air.

“This is by no means a new idea,” says Rod Muttram, formerly of Bombardier Transportation and Railtrack.

“It has been previously suggested as a possible transatlantic transport system. The only novel feature I see is the proposal to put the tubes above existing roads.”

…

Here’s the latest I’ve found on hyperloop, from the Hyperloop Wikipedia entry,

…

As of 2024, some companies continued to pursue technology development under the hyperloop moniker, however, one of the biggest, well funded players, Hyperloop One, declared bankruptcy and ceased operations in 2023.[15]

…

Musk is impatient and impulsive as noted in a September 12, 2023 posting by Mike Masnick on Techdirt, Note: A link has been removed,

The Batshit Crazy Story Of The Day Elon Musk Decided To Personally Rip Servers Out Of A Sacramento Data Center

Back on Christmas Eve [December 24, 2022] of last year there were some reports that Elon Musk was in the process of shutting down Twitter’s Sacramento data center. In that article, a number of ex-Twitter employees were quoted about how much work it would be to do that cleanly, noting that there’s a ton of stuff hardcoded in Twitter code referring to that data center (hold that thought).

That same day, Elon tweeted out that he had “disconnected one of the more sensitive server racks.”

…

Masnick follows with a story of reckless behaviour from someone who should have known better.

Ethics of implants—where to look for more information

While Musk doesn’t use the term when he describes a “human/AI symbiosis” (presumably by way of a neural implant), he’s talking about a cyborg. Here’s a 2018 paper, which looks at some of the implications,

Do you want to be a cyborg? The moderating effect of ethics on neural implant acceptance by Eva Reinares-Lara, Cristina Olarte-Pascual, and Jorge Pelegrín-Borondo. Computers in Human Behavior Volume 85, August 2018, Pages 43-53 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.032

This paper is open access.

Getting back to Neuralink, I have two blog posts that discuss the company and the ethics of brain implants from way back in 2021.

First, there’s Jazzy Benes’ March 1, 2021 posting on the Santa Clara University’s Markkula Center for Applied Ethics blog. It stands out as it includes a discussion of the disabled community’s issues, Note: Links have been removed,

In the heart of Silicon Valley we are constantly enticed by the newest technological advances. With the big influencers Grimes [a Canadian musician and the mother of three children with Elon Musk] and Lil Uzi Vert publicly announcing their willingness to become experimental subjects for Elon Musk’s Neuralink brain implantation device, we are left wondering if future technology will actually give us “the knowledge of the Gods.” Is it part of the natural order for humans to become omniscient beings? Who will have access to the devices? What other ethical considerations must be discussed before releasing such technology to the public?

…

A significant issue that arises from developing technologies for the disabled community is the assumption that disabled persons desire the abilities of what some abled individuals may define as “normal.” Individuals with disabilities may object to technologies intended to make them fit an able-bodied norm. “Normal” is relative to each individual, and it could be potentially harmful to use a deficit view of disability, which means judging a disability as a deficiency. However, this is not to say that all disabled individuals will reject a technology that may enhance their abilities. Instead, I believe it is a consideration that must be recognized when developing technologies for the disabled community, and it can only be addressed through communication with disabled persons. As a result, I believe this is a conversation that must be had with the community for whom the technology is developed–disabled persons.

…

With technologies that aim to address disabilities, we walk a fine line between therapeutics and enhancement. Though not the first neural implant medical device, the Link may have been the first BCI system openly discussed for its potential transhumanism uses, such as “enhanced cognitive abilities, memory storage and retrieval, gaming, telepathy, and even symbiosis with machines.” …

Benes also discusses transhumanism, privacy issues, and consent issues. It’s a thoughtful reading experience.

Second is a July 9, 2021 posting by anonymous on the University of California at Berkeley School of Information blog which provides more insight into privacy and other issues associated with data collection (and introduced me to the concept of decisional interference),

As the development of microchips furthers and advances in neuroscience occur, the possibility for seamless brain-machine interfaces, where a device decodes inputs from the user’s brain to perform functions, becomes more of a reality. These various forms of these technologies already exist. However, technological advances have made implantable and portable devices possible. Imagine a future where humans don’t need to talk to each other, but rather can transmit their thoughts directly to another person. This idea is the eventual goal of Elon Musk, the founder of Neuralink. Currently, Neuralink is one of the main companies involved in the advancement of this type of technology. Analysis of the Neuralink’s technology and their overall mission statement provide an interesting insight into the future of this type of human-computer interface and the potential privacy and ethical concerns with this technology.

…

As this technology further develops, several privacy and ethical concerns come into question. To begin, using Solove’s Taxonomy as a privacy framework, many areas of potential harm are revealed. In the realm of information collection, there is much risk. Brain-computer interfaces, depending on where they are implanted, could have access to people’s most private thoughts and emotions. This information would need to be transmitted to another device for processing. The collection of this information by companies such as advertisers would represent a major breach of privacy. Additionally, there is risk to the user from information processing. These devices must work concurrently with other devices and often wirelessly. Given the widespread importance of cloud computing in much of today’s technology, offloading information from these devices to the cloud would be likely. Having the data stored in a database puts the user at the risk of secondary use if proper privacy policies are not implemented. The trove of information stored within the information collected from the brain is vast. These datasets could be combined with existing databases such as browsing history on Google to provide third parties with unimaginable context on individuals. Lastly, there is risk for information dissemination, more specifically, exposure. The information collected and processed by these devices would need to be stored digitally. Keeping such private information, even if anonymized, would be a huge potential for harm, as the contents of the information may in itself be re-identifiable to a specific individual. Lastly there is risk for invasions such as decisional interference. Brain-machine interfaces would not only be able to read information in the brain but also write information. This would allow the device to make potential emotional changes in its users, which be a major example of decisional interference. …

For the most recent Neuralink and brain implant ethics piece, there’s this February 14, 2024 essay on The Conversation, which, unusually, for this publication was solicited by the editors, Note: Links have been removed,

In January 2024, Musk announced that Neuralink implanted its first chip in a human subject’s brain. The Conversation reached out to two scholars at the University of Washington School of Medicine – Nancy Jecker, a bioethicst, and Andrew Ko, a neurosurgeon who implants brain chip devices – for their thoughts on the ethics of this new horizon in neuroscience.

…

Information about the implant, however, is scarce, aside from a brochure aimed at recruiting trial subjects. Neuralink did not register at ClinicalTrials.gov, as is customary, and required by some academic journals. [all emphases mine]

Some scientists are troubled by this lack of transparency. Sharing information about clinical trials is important because it helps other investigators learn about areas related to their research and can improve patient care. Academic journals can also be biased toward positive results, preventing researchers from learning from unsuccessful experiments.

Fellows at the Hastings Center, a bioethics think tank, have warned that Musk’s brand of “science by press release, while increasingly common, is not science. [emphases mine]” They advise against relying on someone with a huge financial stake in a research outcome to function as the sole source of information.

When scientific research is funded by government agencies or philanthropic groups, its aim is to promote the public good. Neuralink, on the other hand, embodies a private equity model [emphasis mine], which is becoming more common in science. Firms pooling funds from private investors to back science breakthroughs may strive to do good, but they also strive to maximize profits, which can conflict with patients’ best interests.

In 2022, the U.S. Department of Agriculture investigated animal cruelty at Neuralink, according to a Reuters report, after employees accused the company of rushing tests and botching procedures on test animals in a race for results. The agency’s inspection found no breaches, according to a letter from the USDA secretary to lawmakers, which Reuters reviewed. However, the secretary did note an “adverse surgical event” in 2019 that Neuralink had self-reported.

In a separate incident also reported by Reuters, the Department of Transportation fined Neuralink for violating rules about transporting hazardous materials, including a flammable liquid.

…

…the possibility that the device could be increasingly shown to be helpful for people with disabilities, but become unavailable due to loss of research funding. For patients whose access to a device is tied to a research study, the prospect of losing access after the study ends can be devastating. [emphasis mine] This raises thorny questions about whether it is ever ethical to provide early access to breakthrough medical interventions prior to their receiving full FDA approval.

Not registering a clinical trial would seem to suggest there won’t be much oversight. As for Musk’s “science by press release” activities, I hope those will be treated with more skepticism by mainstream media although that seems unlikely given the current situation with journalism (more about that in a future post).

As for the issues associated with private equity models for science research and the problem of losing access to devices after a clinical trial is ended, my April 5, 2022 posting, “Going blind when your neural implant company flirts with bankruptcy (long read)” offers some cautionary tales, in addition to being the most comprehensive piece I’ve published on ethics and brain implants.

My July 17, 2023 posting, “Unveiling the Neurotechnology Landscape: Scientific Advancements, Innovations and Major Trends—a UNESCO report” offers a brief overview of the international scene.