I have two bits about prosthetics, one which focuses on how most of us think of them and another about science fiction fantasies.

Better motor control

This new technology comes via a collaboration between the University of Alberta, the University of New Brunswick (UNB) and Ohio’s Cleveland Clinic, from a March 18, 2018 article by Nicole Ireland for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC) news online,

Rob Anderson was fighting wildfires in Alberta when the helicopter he was in crashed into the side of a mountain. He survived, but lost his left arm and left leg.

More than 10 years after that accident, Anderson, now 39, says prosthetic limb technology has come a long way, and he feels fortunate to be using “top of the line stuff” to help him function as normally as possible. In fact, he continues to work for the Alberta government’s wildfire fighting service.

His powered prosthetic hand can do basic functions like opening and closing, but he doesn’t feel connected to it — and has limited ability to perform more intricate movements with it, such as shaking hands or holding a glass.

Anderson, who lives in Grande Prairie, Alta., compares its function to “doing things with a long pair of pliers.”

“There’s a disconnect between what you’re physically touching and what your body is doing,” he told CBC News.

Anderson is one of four Canadian participants in a study that suggests there’s a way to change that. …

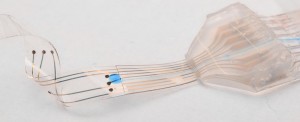

Six people, all of whom had arm amputations from below the elbow or higher, took part in the research. It found that strategically placed vibrating “robots” made them “feel” the movements of their prosthetic hands, allowing them to grasp and grip objects with much more control and accuracy.

All of the participants had all previously undergone a specialized surgical procedure called “targeted re-innervation.” The nerves that had connected to their hands before they were amputated were rewired to link instead to muscles (including the biceps and triceps) in their remaining upper arms and in their chests.

For the study, researchers placed the robotic devices on the skin over those re-innervated muscles and vibrated them as the participants opened, closed, grasped or pinched with their prosthetic hands.

While the vibration was turned on, the participants “felt” their artificial hands moving and could adjust their grip based on the sensation. …

I have an April 24, 2017 posting about a tetraplegic patient who had a number of electrodes implanted in his arms and hands linked to a brain-machine interface and which allowed him to move his hands and arms; the implants were later removed. It is a different problem with a correspondingly different technological solution but there does seem to be increased interest in implanting sensors and electrodes into the human body to increase mobility and/or sensation.

Anderson describes how it ‘feels,

“It was kind of surreal,” Anderson said. “I could visually see the hand go out, I would touch something, I would squeeze it and my phantom hand felt like it was being closed and squeezing on something and it was sending the message back to my brain.

“It was a very strange sensation to actually be able to feel that feedback because I hadn’t in 10 years.”

The feeling of movement in the prosthetic hand is an illusion, the researchers say, since the vibration is actually happening to a muscle elsewhere in the body. But the sensation appeared to have a real effect on the participants.

“They were able to control their grasp function and how much they were opening the hand, to the same degree that someone with an intact hand would,” said study co-author Dr. Jacqueline Hebert, an associate professor in the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Alberta.

…

Although the researchers are encouraged by the study findings, they acknowledge that there was a small number of participants, who all had access to the specialized re-innervation surgery to redirect the nerves from their amputated hands to other parts of their body.

The next step, they say, is to see if they can also simulate the feeling of movement in a broader range of people who have had other types of amputations, including legs, and have not had the re-innervation surgery.

…

Here’s a March 15, 2018 CBC New Brunswick radio interview about the work,

This is a bit longer than most of the embedded audio pieces that I have here but it’s worth it. Sadly, I can’t identify the interviewer who did a very good job with Jon Sensinger, associate director of UNB’s Institute of Biomedical Engineering. One more thing, I noticed that the interviewer made no mention of the University of Alberta in her introduction or in the subsequent interview. I gather regionalism reigns supreme everywhere in Canada. Or, maybe she and Sensinger just forgot. It happens when you’re excited. Also, there were US institutions in Ohio and Virginia that participated in this work.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the team’s paper,

Illusory movement perception improves motor control for prosthetic hands by Paul D. Marasco, Jacqueline S. Hebert, Jon W. Sensinger, Courtney E. Shell, Jonathon S. Schofield, Zachary C. Thumser, Raviraj Nataraj, Dylan T. Beckler, Michael R. Dawson, Dan H. Blustein, Satinder Gill, Brett D. Mensh, Rafael Granja-Vazquez, Madeline D. Newcomb, Jason P. Carey, and Beth M. Orzell. Science Translational Medicine 14 Mar 2018: Vol. 10, Issue 432, eaao6990 DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao6990

This paper is open access.

Superprostheses and our science fiction future

A March 20, 2018 news item on phys.org features an essay on about superprostheses and/or assistive devices,

Assistive devices may soon allow people to perform virtually superhuman feats. According to Robert Riener, however, there are more pressing goals than developing superhumans.

What had until recently been described as a futuristic vision has become a reality: the first self-declared “cyborgs” have had chips implanted in their bodies so that they can open doors and make cashless payments. The latest robotic hand prostheses succeed in performing all kinds of grips and tasks requiring dexterity. Parathletes fitted with running and spring prostheses compete – and win – against the best, non-impaired athletes. Then there are robotic pets and talking humanoid robots adding a bit of excitement to nursing homes.

Some media are even predicting that these high-tech creations will bring about forms of physiological augmentation overshadowing humans’ physical capabilities in ways never seen before. For instance, hearing aids are eventually expected to offer the ultimate in hearing; retinal implants will enable vision with a sharpness rivalling that of any eagle; motorised exoskeletons will transform soldiers into tireless fighting machines.

Visions of the future: the video game Deus Ex: Human Revolution highlights the emergence of physiological augmentation. (Visualisations: Square Enix) Courtesy: ETH Zurich

Professor Robert Riener uses the image above to illustrate the notion of superprosthese in his March 20, 2018 essay on the ETH Zurich website,

All of these prophecies notwithstanding, our robotic transformation into superheroes will not be happening in the immediate future and can still be filed under Hollywood hero myths. Compared to the technology available today, our bodies are a true marvel whose complexity and performance allows us to perform an extremely wide spectrum of tasks. Hundreds of efficient muscles, thousands of independently operating motor units along with millions of sensory receptors and billions of nerve cells allow us to perform delicate and detailed tasks with tweezers or lift heavy loads. Added to this, our musculoskeletal system is highly adaptable, can partly repair itself and requires only minimal amounts of energy in the form of relatively small amounts of food consumed.

Machines will not be able to match this any time soon. Today’s assistive devices are still laboratory experiments or niche products designed for very specific tasks. Markus Rehm, an athlete with a disability, does not use his innovative spring prosthesis to go for walks or drive a car. Nor can today’s conventional arm prostheses help a person tie their shoes or button up their shirt. Lifting devices used for nursing care are not suitable for helping with personal hygiene tasks or in psychotherapy. And robotic pets quickly lose their charm the moment their batteries die.

Solving real problems

There is no denying that advances continue to be made. Since the scientific and industrial revolutions, we have become dependent on relentless progress and growth, and we can no longer separate today’s world from this development. There are, however, more pressing issues to be solved than creating superhumans.

On the one hand, engineers need to dedicate their efforts to solving the real problems of patients, the elderly and people with disabilities. Better technical solutions are needed to help them lead normal lives and assist them in their work. We need motorised prostheses that also work in the rain and wheelchairs that can manoeuvre even with snow on the ground. Talking robotic nurses also need to be understood by hard-of-hearing pensioners as well as offer simple and dependable interactivity. Their batteries need to last at least one full day to be recharged overnight.

In addition, financial resources need to be available so that all people have access to the latest technologies, such as a high-quality household prosthesis for the family man, an extra prosthesis for the avid athlete or a prosthesis for the pensioner. [emphasis mine]

Breaking down barriers

What is just as important as the ongoing development of prostheses and assistive devices is the ability to minimise or eliminate physical barriers. Where there are no stairs, there is no need for elaborate special solutions like stair lifts or stairclimbing wheelchairs – or, presumably, fully motorised exoskeletons.

Efforts also need to be made to transform the way society thinks about people with disabilities. More acknowledgement of the day-to-day challenges facing patients with disabilities is needed, which requires that people be confronted with the topic of disability when they are still children. Such projects must be promoted at home and in schools so that living with impairments can also attain a state of normality and all people can partake in society. It is therefore also necessary to break down mental barriers.

The road to a virtually superhuman existence is still far and long. Anyone reading this text will not live to see it. In the meantime, the task at hand is to tackle the mundane challenges in order to simplify people’s daily lives in ways that do not require technology, that allow people to be active participants and improve their quality of life – instead of wasting our time getting caught up in cyborg euphoria and digital mania.

I’m struck by Riener’s reference to financial resources and access. Sensinger mentions financial resources in his CBC radio interview although his concern is with convincing funders that prostheses that mimic ‘feeling’ are needed.

I’m also struck by Riener’s discussion about nontechnological solutions for including people with all kinds of abilities and disabilities.

There was no grand plan for combining these two news bits; I just thought they were interesting together.