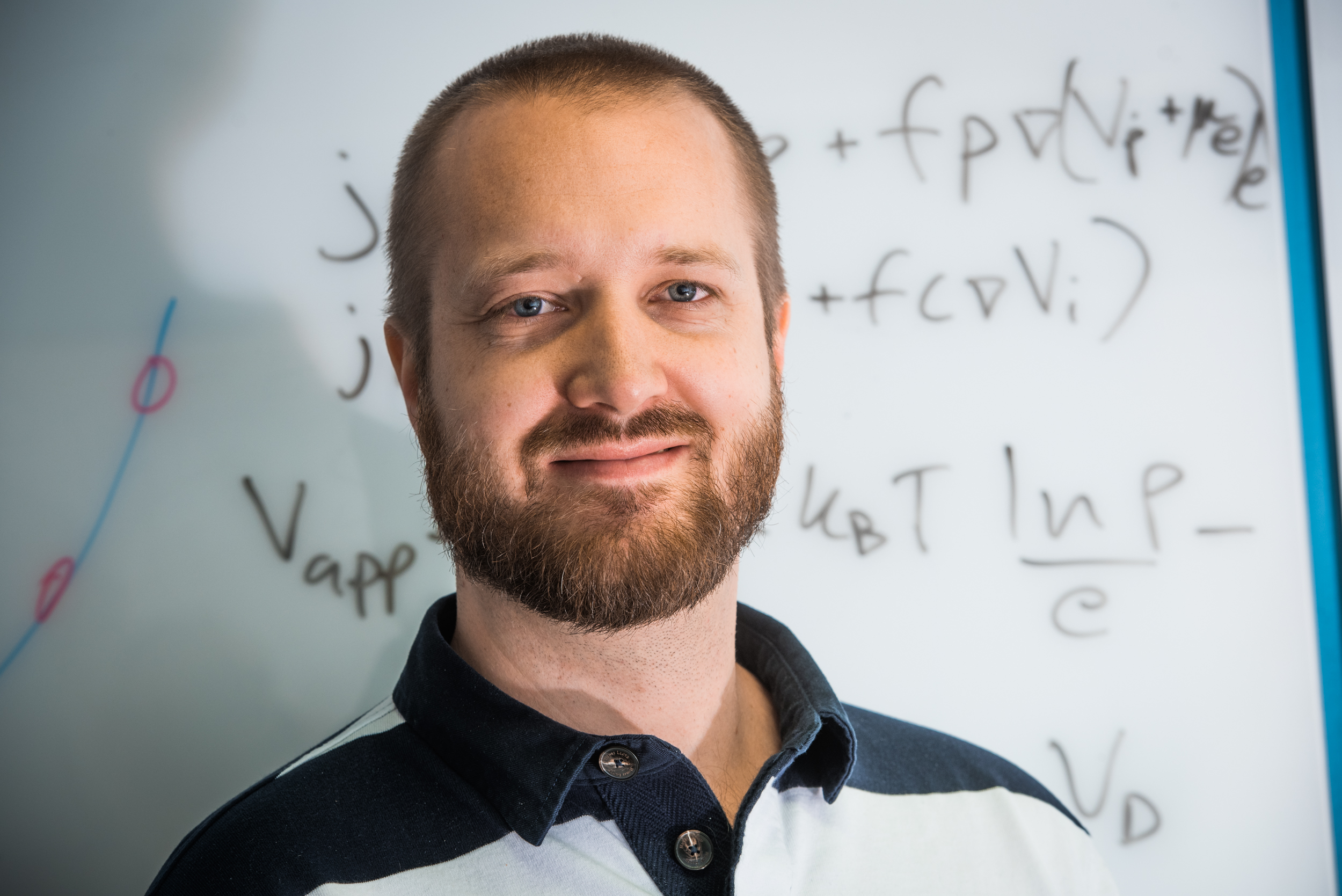

Ravinder Dahiya, Carlos García Núñez, and their colleagues at the University of Glasgow (Scotland) strike again (see my May 10, 2017 posting for their first ‘solar-powered graphene skin’ research announcement). Last time it was all about robots and prosthetics, this time they’ve focused on wearable technology according to a July 18, 2018 news item on phys.org,

A new form of solar-powered supercapacitor could help make future wearable technologies lighter and more energy-efficient, scientists say.

In a paper published in the journal Nano Energy, researchers from the University of Glasgow’s Bendable Electronics and Sensing Technologies (BEST) group describe how they have developed a promising new type of graphene supercapacitor, which could be used in the next generation of wearable health sensors.

A July 18, 2018 University of Glasgow press release, which originated the news item, explains further,

Currently, wearable systems generally rely on relatively heavy, inflexible batteries, which can be uncomfortable for long-term users. The BEST team, led by Professor Ravinder Dahiya, have built on their previous success in developing flexible sensors by developing a supercapacitor which could power health sensors capable of conforming to wearer’s bodies, offering more comfort and a more consistent contact with skin to better collect health data.

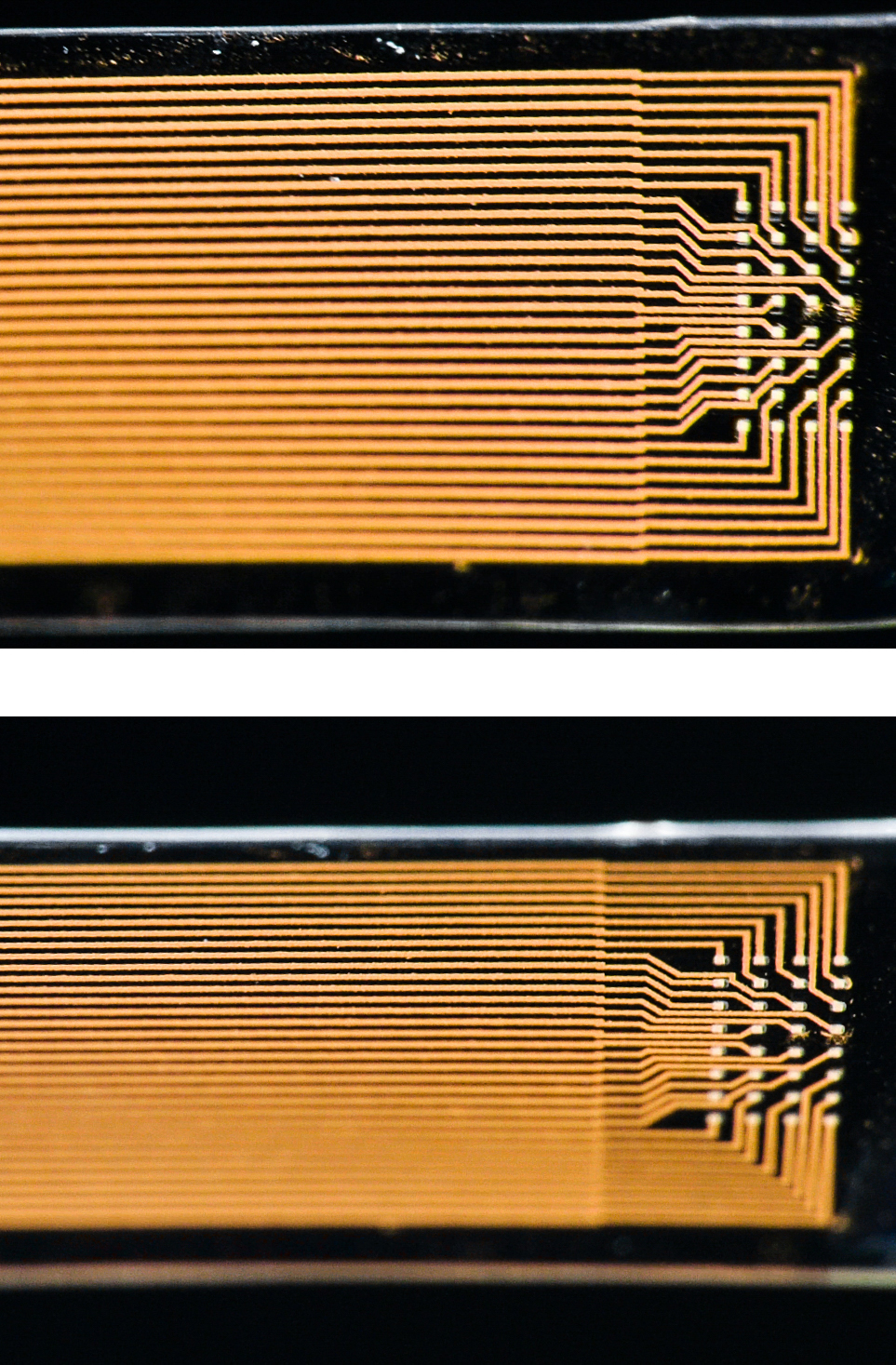

Their new supercapacitor uses layers of flexible, three-dimensional porous foam formed from graphene and silver to produce a device capable of storing and releasing around three times more power than any similar flexible supercapacitor. The team demonstrated the durability of the supercapacitor, showing that it provided power consistently across 25,000 charging and discharging cycles.

They have also found a way to charge the system by integrating it with flexible solar powered skin already developed by the BEST group, effectively creating an entirely self-charging system, as well as a pH sensor which uses wearer’s sweat to monitor their health.

Professor Dahiya said: “We’re very pleased by the progress this new form of solar-powered supercapacitor represents. A flexible, wearable health monitoring system which only requires exposure to sunlight to charge has a lot of obvious commercial appeal, but the underlying technology has a great deal of additional potential.

“This research could take the wearable systems for health monitoring to remote parts of the world where solar power is often the most reliable source of energy, and it could also increase the efficiency of hybrid electric vehicles. We’re already looking at further integrating the technology into flexible synthetic skin which we’re developing for use in advanced prosthetics.” [emphasis mine]

In addition to the team’s work on robots, prosthetics, and graphene ‘skin’ mentioned in the May 10, 2017 posting the team is working on a synthetic ‘brainy’ skin for which they have just received £1.5m funding from the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC).

Brainy skin

A July 3, 2018 University of Glasgow press release discusses the proposed work in more detail,

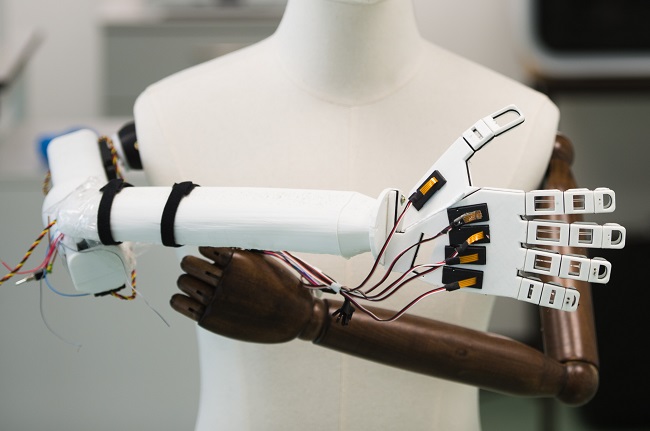

A robotic hand covered in ‘brainy skin’ that mimics the human sense of touch is being developed by scientists.

University of Glasgow’s Professor Ravinder Dahiya has plans to develop ultra-flexible, synthetic Brainy Skin that ‘thinks for itself’.

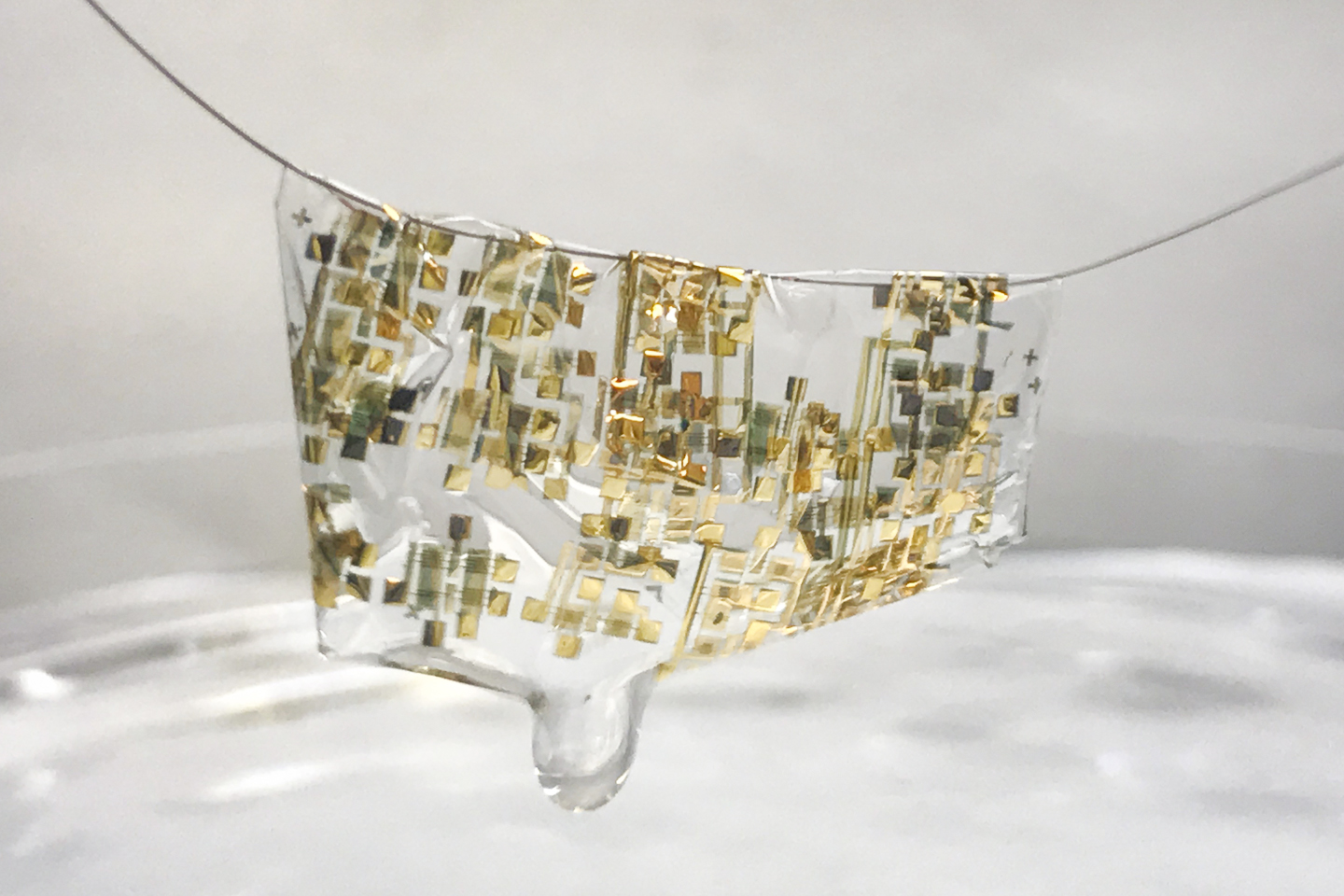

The super-flexible, hypersensitive skin may one day be used to make more responsive prosthetics for amputees, or to build robots with a sense of touch.

Brainy Skin reacts like human skin, which has its own neurons that respond immediately to touch rather than having to relay the whole message to the brain.

This electronic ‘thinking skin’ is made from silicon based printed neural transistors and graphene – an ultra-thin form of carbon that is only an atom thick, but stronger than steel.

The new version is more powerful, less cumbersome and would work better than earlier prototypes, also developed by Professor Dahiya and his Bendable Electronics and Sensing Technologies (BEST) team at the University’s School of Engineering.

His futuristic research, called neuPRINTSKIN (Neuromorphic Printed Tactile Skin), has just received another £1.5m funding from the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC).

Professor Dahiya said: “Human skin is an incredibly complex system capable of detecting pressure, temperature and texture through an array of neural sensors that carry signals from the skin to the brain.

“Inspired by real skin, this project will harness the technological advances in electronic engineering to mimic some features of human skin, such as softness, bendability and now, also sense of touch. This skin will not just mimic the morphology of the skin but also its functionality.

“Brainy Skin is critical for the autonomy of robots and for a safe human-robot interaction to meet emerging societal needs such as helping the elderly.”

This latest advance means tactile data is gathered over large areas by the synthetic skin’s computing system rather than sent to the brain for interpretation.

With additional EPSRC funding, which extends Professor Dahiya’s fellowship by another three years, he plans to introduce tactile skin with neuron-like processing. This breakthrough in the tactile sensing research will lead to the first neuromorphic tactile skin, or ‘brainy skin.’

To achieve this, Professor Dahiya will add a new neural layer to the e-skin that he has already developed using printing silicon nanowires.

Professor Dahiya added: “By adding a neural layer underneath the current tactile skin, neuPRINTSKIN will add significant new perspective to the e-skin research, and trigger transformations in several areas such as robotics, prosthetics, artificial intelligence, wearable systems, next-generation computing, and flexible and printed electronics.”

The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) is part of UK Research and Innovation, a non-departmental public body funded by a grant-in-aid from the UK government.

EPSRC is the main funding body for engineering and physical sciences research in the UK. By investing in research and postgraduate training, the EPSRC is building the knowledge and skills base needed to address the scientific and technological challenges facing the nation.

Its portfolio covers a vast range of fields from healthcare technologies to structural engineering, manufacturing to mathematics, advanced materials to chemistry. The research funded by EPSRC has impact across all sectors. It provides a platform for future UK prosperity by contributing to a healthy, connected, resilient, productive nation.

It’s fascinating to note how these pieces of research fit together for wearable technology and health monitoring and creating more responsive robot ‘skin’ and, possibly, prosthetic devices that would allow someone to feel again.

The latest research paper

Getting back the solar-charging supercapacitors mentioned in the opening, here’s a link to and a citation for the team’s latest research paper,

Flexible self-charging supercapacitor based on graphene-Ag-3D graphene foam electrodes by Libu Manjakka, Carlos García Núñez, Wenting Dang, Ravinder Dahiya. Nano Energy Volume 51, September 2018, Pages 604-612 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.06.072

This paper is open access.