According to a May 20,2020 McGill University news release (also on EurkekAltert), a team of Canadian and Italian researchers has broken new ground in materials science (Note: There’s a press release I found a bit more accessible and therefore informative coming up after this one),

A study by a team of researchers from Canada and Italy recently published in Nature Materials could usher in a revolutionary development in materials science, leading to big changes in the way companies create modern electronics.

The goal was to develop two-dimensional materials, which are a single atomic layer thick, with added functionality to extend the revolutionary developments in materials science that started with the discovery of graphene in 2004.

In total, 19 authors worked on this paper from INRS [Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique], McGill {University], Lakehead [University], and Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, the national research council in Italy.

This work opens exciting new directions, both theoretical and experimental. The integration of this system into a device (e.g. transistors) may lead to outstanding performances. In addition, these results will foster more studies on a wide range of two-dimensional conjugated polymers with different lattice symmetries, thereby gaining further insights into the structure vs. properties of these systems.

The Italian/Canadian team demonstrated the synthesis of large-scale two-dimensional conjugated polymers, also thoroughly characterizing their electronic properties. They achieved success by combining the complementary expertise of organic chemists and surface scientists.

“This work represents an exciting development in the realization of functional two-dimensional materials beyond graphene,” said Mark Gallagher, a Physics professor at Lakehead University.

“I found it particularly rewarding to participate in this collaboration, which allowed us to combine our expertise in organic chemistry, condensed matter physics, and materials science to achieve our goals.”

Dmytro Perepichka, a professor and chair of Chemistry at McGill University, said they have been working on this research for a long time.

“Structurally reconfigurable two-dimensional conjugated polymers can give a new breadth to applications of two-dimensional materials in electronics,” Perepichka said.

“We started dreaming of them more than 15 years ago. It’s only through this four-way collaboration, across the country and between the continents, that this dream has become the reality.”

Federico Rosei, a professor at the Énergie Matériaux Télécommunications Research Centre of the Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS) in Varennes who holds the Canada Research Chair in Nanostructured Materials since 2016, said they are excited about the results of this collaboration.

“These results provide new insights into mechanisms of surface reactions at a fundamental level and simultaneously yield a novel material with outstanding properties, whose existence had only been predicted theoretically until now,” he said.

About this study

“Synthesis of mesoscale ordered two-dimensional π-conjugated polymers with semiconducting properties” by G. Galeotti et al. was published in Nature Materials.

This research was partially supported by a project Grande Rilevanza Italy-Quebec of the Italian Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale, Direzione Generale per la Promozione del Sistema Paese, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Fonds Québécois de la recherche sur la nature et les technologies and a US Army Research Office. Federico Rosei is also grateful to the Canada Research Chairs program for funding and partial salary support.

About McGill University

Founded in Montreal, Quebec, in 1821, McGill is a leading Canadian post-secondary institution. It has two campuses, 11 faculties, 13 professional schools, 300 programs of study and over 40,000 students, including more than 10,200 graduate students. McGill attracts students from over 150 countries around the world, its 12,800 international students making up 31% per cent of the student body. Over half of McGill students claim a first language other than English, including approximately 19% of our students who say French is their mother tongue.

About the INRS

The Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS) is the only institution in Québec dedicated exclusively to graduate level university research and training. The impacts of its faculty and students are felt around the world. INRS proudly contributes to societal progress in partnership with industry and community stakeholders, both through its discoveries and by training new researchers and technicians to deliver scientific, social, and technological breakthroughs in the future.Lakehead University

Lakehead University is a fully comprehensive university with approximately 9,700 full-time equivalent students and over 2,000 faculty and staff at two campuses in Orillia and Thunder Bay, Ontario. Lakehead has 10 faculties, including Business Administration, Education, Engineering, Graduate Studies, Health & Behavioural Sciences, Law, Natural Resources Management, the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Science & Environmental Studies, and Social Sciences & Humanities. In 2019, Maclean’s 2020 University Rankings, once again, included Lakehead University among Canada’s Top 10 primarily undergraduate universities, while Research Infosource named Lakehead ‘Research University of the Year’ in its category for the fifth consecutive year. Visit www.lakeheadu.ca

I’m a little surprised there wasn’t a quote from one of the Italian researchers in the McGill news release but then there isn’t a quote in this slightly more accessible May 18, 2020 Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche press release either,

Graphene’s isolation took the world by surprise and was meant to revolutionize modern electronics. However, it was soon realized that its intrinsic properties limit the utilization in our daily electronic devices. When a concept of Mathematics, namely Topology, met the field of on-surface chemistry, new materials with exotic features were theoretically discovered. Topological materials exhibit technological relevant properties such as quantum hall conductivity that are protected by a concept similar to the comparison of a coffee mug and a donut. These structures can be synthesized by the versatile molecular engineering toolbox that surface reactions provide. Nevertheless, the realization of such a material yields access to properties that suit the figure of merits for modern electronic application and could eventually for example lead to solve the ever-increasing heat conflict in chip design. However, problems such as low crystallinity and defect rich structures prevented the experimental observation and kept it for more than a decade a playground only investigated theoretically.

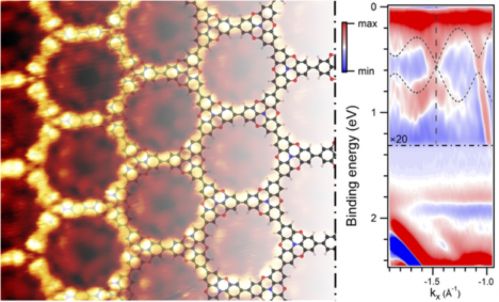

An international team of scientists from Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (Centre Energie, Matériaux et Télécommunications), McGill University and Lakehead University, both located in Canada, and the SAMOS laboratory of the Istituto di Struttura della Materia (Cnr), led by Giorgio Contini, demonstrates, in a recent publication on Nature Materials, that the synthesis of two-dimensional π-conjugated polymers with topological Dirac cone and flats bands became a reality allowing a sneak peek into the world of organic topological materials.

Complementary work of organic chemists and surface scientists lead to two-dimensional polymers on a mesoscopic scale and granted access to their electronic properties. The band structure of the topological polymer reveals both flat bands and a Dirac cone confirming the prediction of theory. The observed coexistence of both structures is of particular interest, since whereas Dirac cones yield massless charge carriers (a band velocity of the same order of magnitude of graphene has been obtained), necessary for technological applications, flat bands quench the kinetic energy of charge carriers and could give rise to intriguing phenomena such as the anomalous Hall effect, surface superconductivity or superfluid transport.

This work paths multiple new roads – both theoretical and experimental nature. The integration of this topological polymer into a device such as transistors possibly reveals immense performance. On the other hand, it will foster many researchers to explore a wide range of two-dimensional polymers with different lattice symmetries, obtaining insight into the relationship between geometrical and electrical topology, which would in return be beneficial to fine tune a-priori theoretical studies. These materials – beyond graphene – could be then used for both their intrinsic properties as well as their interplay in new heterostructure designs.

The authors are currently exploring the practical use of the realized material trying to integrate it into transistors, pushing toward a complete designing of artificial topological lattices.

This work was partially supported by a project Grande Rilevanza Italy-Quebec of the Italian Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale (MAECI), Direzione Generale per la Promozione del Sistema Paese.

The Italians also included an image to accompany their press release,

My heart sank when I saw the number of authors for this paper (WordPress no longer [since their Christmas 2018 update] makes it easy to add the author’s names quickly to the ‘tags field’). Regardless and in keeping with my practice, here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Synthesis of mesoscale ordered two-dimensional π-conjugated polymers with semiconducting properties by G. Galeotti, F. De Marchi, E. Hamzehpoor, O. MacLean, M. Rajeswara Rao, Y. Chen, L. V. Besteiro, D. Dettmann, L. Ferrari, F. Frezza, P. M. Sheverdyaeva, R. Liu, A. K. Kundu, P. Moras, M. Ebrahimi, M. C. Gallagher, F. Rosei, D. F. Perepichka & G. Contini. Nature Materials (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-0682-z Published 18 May 2020

This paper is behind a paywall.