Fish leather

Before getting to Futures, here’s a brief excerpt from a June 11, 2021 Smithsonian Magazine exhibition preview article by Gia Yetikyel about one of the contributors, Elisa Palomino-Perez (Note: A link has been removed),

Elisa Palomino-Perez sheepishly admits to believing she was a mermaid as a child. Growing up in Cuenca, Spain in the 1970s and ‘80s, she practiced synchronized swimming and was deeply fascinated with fish. Now, the designer’s love for shiny fish scales and majestic oceans has evolved into an empowering mission, to challenge today’s fashion industry to be more sustainable, by using fish skin as a material.

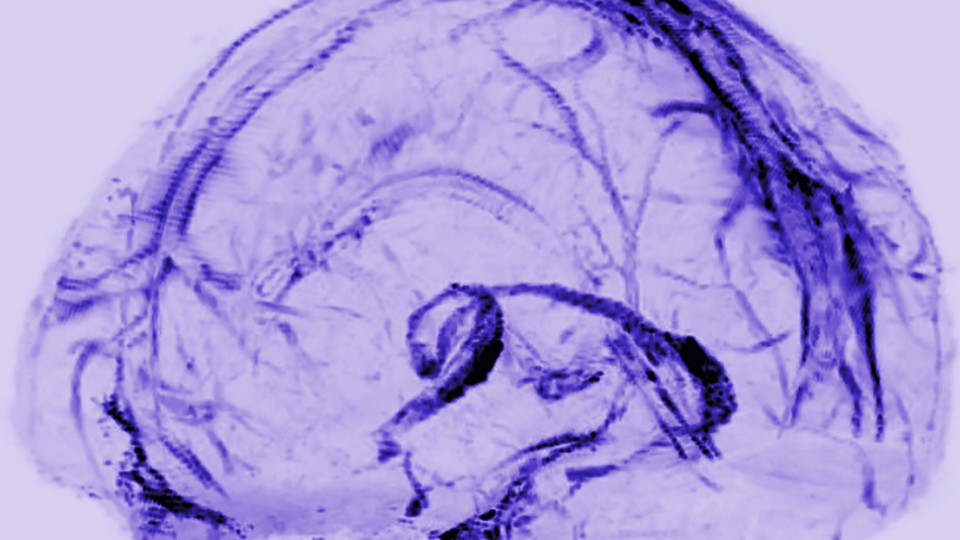

Luxury fashion is no stranger to the artist, who has worked with designers like Christian Dior, John Galliano and Moschino in her 30-year career. For five seasons in the early 2000s, Palomino-Perez had her own fashion brand, inspired by Asian culture and full of color and embroidery. It was while heading a studio for Galliano in 2002 that she first encountered fish leather: a material made when the skin of tuna, cod, carp, catfish, salmon, sturgeon, tilapia or pirarucu gets stretched, dried and tanned.

…

The history of using fish leather in fashion is a bit murky. The material does not preserve well in the archeological record, and it’s been often overlooked as a “poor person’s” material due to the abundance of fish as a resource. But Indigenous groups living on coasts and rivers from Alaska to Scandinavia to Asia have used fish leather for centuries. Icelandic fishing traditions can even be traced back to the ninth century. While assimilation policies, like banning native fishing rights, forced Indigenous groups to change their lifestyle, the use of fish skin is seeing a resurgence. Its rise in popularity in the world of sustainable fashion has led to an overdue reclamation of tradition for Indigenous peoples.

In 2017, Palomino-Perez embarked on a PhD in Indigenous Arctic fish skin heritage at London College of Fashion, which is a part of the University of the Arts in London (UAL), where she received her Masters of Arts in 1992. She now teaches at Central Saint Martins at UAL, while researching different ways of crafting with fish skin and working with Indigenous communities to carry on the honored tradition.

…

Yetikyel’s article is fascinating (apparently Nike has used fish leather in one of its sports shoes) and I encourage you to read her June 11, 2021 article, which also covers the history of fish leather use amongst indigenous peoples of the world.

I did some digging and found a few more stories about fish leather. The earlier one is a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) November 16, 2017 online news article by Jane Adey,

Designer Arndis Johannsdottir holds up a stunning purse, decorated with shiny strips of gold and silver leather at Kirsuberjatred, an art and design store in downtown Reykjavik, Iceland.

The purse is one of many in a colourful window display that’s drawing in buyers.

Johannsdottir says customers’ eyes often widen when they discover the metallic material is fish skin.

…

Johannsdottir, a fish-skin designing pioneer, first came across the product 35 years ago.

She was working as a saddle smith when a woman came into her shop with samples of fish skin her husband had tanned after the war. Hundreds of pieces had been lying in a warehouse for 40 years.

“Nobody wanted it because plastic came on the market and everybody was fond of plastic,” she said.

“After 40 years, it was still very, very strong and the colours were beautiful and … I fell in love with it immediately.”

Johannsdottir bought all the skins the woman had to offer, gave up saddle making and concentrated on fashionable fish skin.

…

Adey’s November 16, 2017 article goes on to mention another Icelandic fish leather business looking to make fish leather a fashion staple.

Chloe Williams’s April 28, 2020 article for Hakkai Magazine explores the process of making fish leather and the new interest in making it,

Tracy Williams slaps a plastic cutting board onto the dining room table in her home in North Vancouver, British Columbia. Her friend, Janey Chang, has already laid out the materials we will need: spoons, seashells, a stone, and snack-sized ziplock bags filled with semi-frozen fish. Williams says something in Squamish and then translates for me: “You are ready to make fish skin.”

Chang peels a folded salmon skin from one of the bags and flattens it on the table. “You can really have at her,” she says, demonstrating how to use the edge of the stone to rub away every fiber of flesh. The scales on the other side of the skin will have to go, too. On a sockeye skin, they come off easily if scraped from tail to head, she adds, “like rubbing a cat backwards.” The skin must be clean, otherwise it will rot or fail to absorb tannins that will help transform it into leather.

Williams and Chang are two of a scant but growing number of people who are rediscovering the craft of making fish skin leather, and they’ve agreed to teach me their methods. The two artists have spent the past five or six years learning about the craft and tying it back to their distinct cultural perspectives. Williams, a member of the Squamish Nation—her ancestral name is Sesemiya—is exploring the craft through her Indigenous heritage. Chang, an ancestral skills teacher at a Squamish Nation school, who has also begun teaching fish skin tanning in other BC communities, is linking the craft to her Chinese ancestry.

…

Before the rise of manufactured fabrics, Indigenous peoples from coastal and riverine regions around the world tanned or dried fish skins and sewed them into clothing. The material is strong and water-resistant, and it was essential to survival. In Japan, the Ainu crafted salmon skin into boots, which they strapped to their feet with rope. Along the Amur River in northeastern China and Siberia, Hezhen and Nivkh peoples turned the material into coats and thread. In northern Canada, the Inuit made clothing, and in Alaska, several peoples including the Alutiiq, Athabascan, and Yup’ik used fish skins to fashion boots, mittens, containers, and parkas. In the winter, Yup’ik men never left home without qasperrluk—loose-fitting, hooded fish skin parkas—which could double as shelter in an emergency. The men would prop up the hood with an ice pick and pin down the edges to make a tent-like structure.

…

On a Saturday morning, I visit Aurora Skala in Saanich on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, to learn about the step after scraping and tanning: softening. Skala, an anthropologist working in language revitalization, has taken an interest in making fish skin leather in her spare time. When I arrive at her house, a salmon skin that she has tanned in an acorn infusion—a cloudy, brown liquid now resting in a jar—is stretched out on the kitchen counter, ready to be worked.

Skala dips her fingers in a jar of sunflower oil and rubs it on her hands before massaging it into the skin. The skin smells only faintly of fish; the scent reminds me of salt and smoke, though the skin has been neither salted nor smoked. “Once you start this process, you can’t stop,” she says. If the skin isn’t worked consistently, it will stiffen as it dries.

Softening the leather with oil takes about four hours, Skala says. She stretches the skin between clenched hands, pulling it in every direction to loosen the fibers while working in small amounts of oil at a time. She’ll also work her skins across other surfaces for extra softening; later, she’ll take this piece outside and rub it back and forth along a metal cable attached to a telephone pole. Her pace is steady, unhurried, soothing. Back in the day, people likely made fish skin leather alongside other chores related to gathering and processing food or fibers, she says. The skin will be done when it’s soft and no longer absorbs oil.

…

Onto the exhibition.

Futures (November 20, 2021 to July 6, 2022 at the Smithsonian)

A February 24, 2021 Smithsonian Magazine article by Meilan Solly serves as an announcement for the Futures exhibition/festival (Note: Links have been removed),

When the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building (AIB) opened to the public in 1881, observers were quick to dub the venue—then known as the National Museum—America’s “Palace of Wonders.” It was a fitting nickname: Over the next century, the site would go on to showcase such pioneering innovations as the incandescent light bulb, the steam locomotive, Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis and space-age rockets.

“Futures,” an ambitious, immersive experience set to open at AIB this November, will act as a “continuation of what the [space] has been meant to do” from its earliest days, says consulting curator Glenn Adamson. “It’s always been this launchpad for the Smithsonian itself,” he adds, paving the way for later museums as “a nexus between all of the different branches of the [Institution].” …

Part exhibition and part festival, “Futures”—timed to coincide with the Smithsonian’s 175th anniversary—takes its cue from the world’s fairs of the 19th and 20th centuries, which introduced attendees to the latest technological and scientific developments in awe-inspiring celebrations of human ingenuity. Sweeping in scale (the building-wide exploration spans a total of 32,000 square feet) and scope, the show is set to feature historic artifacts loaned from numerous Smithsonian museums and other institutions, large-scale installations, artworks, interactive displays and speculative designs. It will “invite all visitors to discover, debate and delight in the many possibilities for our shared future,” explains AIB director Rachel Goslins in a statement.

…

“Futures” is split into four thematic halls, each with its own unique approach to the coming centuries. “Futures Past” presents visions of the future imagined by prior generations, as told through objects including Alexander Graham Bell’s experimental telephone, an early android and a full-scale Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome. “In hindsight, sometimes [a prediction is] amazing,” says Adamson, who curated the history-centric section. “Sometimes it’s sort of funny. Sometimes it’s a little dismaying.”

…

“Futures That Work” continues to explore the theme of technological advancement, but with a focus on problem-solving rather than the lessons of the past. Climate change is at the fore of this section, with highlighted solutions ranging from Capsula Mundi’s biodegradable burial urns to sustainable bricks made out of mushrooms and purely molecular artificial spices that cut down on food waste while preserving natural resources.

“Futures That Inspire,” meanwhile, mimics AIB’s original role as a place of wonder and imagination. “If I were bringing a 7-year-old, this is probably where I would take them first,” says Adamson. “This is where you’re going to be encountering things that maybe look a bit more like science fiction”—for instance, flying cars, self-sustaining floating cities and Afrofuturist artworks.

The final exhibition hall, “Futures That Unite,” emphasizes human relationships, discussing how connections between people can produce a more equitable society. Among others, the list of featured projects includes (Im)possible Baby, a speculative design endeavor that imagines what same-sex couples’ children might look like if they shared both parents’ DNA, and Not The Only One (N’TOO), an A.I.-assisted oral history project. [all emphases mine]

…

I haven’t done justice to Solly’s February 24, 2021 article, which features embedded images and offers a more hopeful view of the future than is currently the fashion.

Futures asks: Would you like to plan the future?

Nate Berg’s November 22, 2021 article for Fast Company features an interactive urban planning game that’s part of the Futures exhibition/festival,

The Smithsonian Institution wants you to imagine the almost ideal city block of the future. Not the perfect block, not utopia, but the kind of urban place where you get most of what you want, and so does everybody else.

Call it urban design by compromise. With a new interactive multiplayer game, the museum is hoping to show that the urban spaces of the future can achieve mutual goals only by being flexible and open to the needs of other stakeholders.

…

The game is designed for three players, each in the role of either the city’s mayor, a real estate developer or an ecologist. The roles each have their own primary goals – the mayor wants a well-served populace, the developer wants to build successful projects, and the ecologist wants the urban environment to coexist with the natural environment. Each role takes turns adding to the block, either in discrete projects or by amending what another player has contributed. Options are varied, but include everything from traditional office buildings and parks to community centers and algae farms. The players each try to achieve their own goals on the block, while facing the reality that other players may push the design in unexpected directions. These tradeoffs and their impact on the block are explained by scores on four basic metrics: daylight, carbon footprint, urban density, and access to services. How each player builds onto the block can bring scores up or down.

…

To create the game, the Smithsonian teamed up with Autodesk, the maker of architectural design tools like AutoCAD, an industry standard. Autodesk developed a tool for AI-based generative design that offers up options for a city block’s design, using computing power to make suggestions on what could go where and how aiming to achieve one goal, like boosting residential density, might detract from or improve another set of goals, like creating open space. “Sometimes you’ll do something that you think is good but it doesn’t really help the overall score,” says Brian Pene, director of emerging technology at Autodesk. “So that’s really showing people to take these tradeoffs and try attributes other than what achieves their own goals.” The tool is meant to show not how AI can generate the perfect design, but how the differing needs of various stakeholders inevitably require some tradeoffs and compromises.

Futures online and in person

Here are links to Futures online and information about visiting in person,

For its 175th anniversary, the Smithsonian is looking forward.

What do you think of when you think of the future? FUTURES is the first building-wide exploration of the future on the National Mall. Designed by the award-winning Rockwell Group, FUTURES spans 32,000 square feet inside the Arts + Industries Building. Now on view until July 6, 2022, FUTURES is your guide to a vast array of interactives, artworks, technologies, and ideas that are glimpses into humanity’s next chapter. You are, after all, only the latest in a long line of future makers.

Smell a molecule. Clean your clothes in a wetland. Meditate with an AI robot. Travel through space and time. Watch water being harvested from air. Become an emoji. The FUTURES is yours to decide, debate, delight. We invite you to dream big, and imagine not just one future, but many possible futures on the horizon—playful, sustainable, inclusive. In moments of great change, we dare to be hopeful. How will you create the future you want to live in?

…

Happy New Year!