There’s a very interesting June 20, 2014 posting by Charles Day on his Dayside blog (located on the Physics Today website). Day manages to relate the Game of Thrones tv series to nuclear power and nanotechnology,

The military technology of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin’s series of fantasy novels, is medieval with an admixture of the supernatural. Dragons aside, among the most prized weapons are swords made from Valyrian steel, which are lighter, stronger, and sharper than ordinary steel swords.

Like many of the features in the rich world of the novels and their TV adaptation, Game of Thrones, Valyrian steel has a historical inspiration. Sometime before 300 BC, metalworkers in Southern India discovered a way to make small cakes of high-carbon steel known as wootz. Thanks to black wavy bands of Fe3C particles that pervade the metal, wootz steel was already strong. …

Perhaps because the properties of wootz and Damascus steels depended, in part, on a particular kind of iron ore, the ability of metallurgists to make the alloys was lost sometime in the 18th century. In A Song of Ice and Fire, the plot plays out during an era in which making Valyrian steel is a long-lost art.

Martin’s knowledge of metallurgy is perhaps shaky. …

Interestingly, the comments on the blog posting largely concern themselves with whether George RR Martin knows anything about metallurgy. The consensus being that he does and that the problems in the Game of Thrones version of metallurgy lie with the series writers.

I first came across the Damascus steel, wootz, and carbon nanotube story in 2008 and provided a concise description on my Nanotech Mysteries wiki Middle Ages page,

Damascus steel blades were first made in the 8th century CE when they acquired a legendary status as unlike other blades they were able to cut through bone and stone while remaining sharp enough to cut a piece of silk. They were also flexible which meant they didn’t break off easily in a sword fight. The secret for making the blades died (history does not record how) about 1700 CE and there hasn’t been a new blade since.

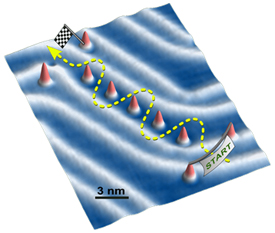

The blades were generally made from metal ingots prepared in India using special recipes which probably put just the right amount of carbon and other impurities into the iron. By following these recipes and following specific forging techniques craftsmen ended up making nanotubes … When these blades were nearly finished, blacksmiths would etch them with acid. This brought out the wavy light and dark lines that make Damascus swords easy to recognize.

It turns out part of the secret to the blade is nanotechnology. Scientists discovered this by looking at a Damascus steel blade from 1700 under an electron microscope. It seems those unknown smiths were somehow encasing cementite nanowires in carbon nanotubes then forging them into the steel blades giving them their legendary strength and flexibility.

The reference information I used then seems to be no longer available online but there is this more than acceptable alternative, a Sept. 27, 2008 postiing by Ed Yong from his Not Exactly Rocket Science blog (on ScienceBlogs.com; Note: A link has been removed),

In medieval times, crusading Christian knights cut a swathe through the Middle East in an attempt to reclaim Jerusalem from the Muslims. The Muslims in turn cut through the invaders using a very special type of sword, which quickly gained a mythical reputation among the Europeans. These ‘Damascus blades‘ were extraordinarily strong, but still flexible enough to bend from hilt to tip. And they were reputedly so sharp that they could cleave a silk scarf floating to the ground, just as readily as a knight’s body.

They were superlative weapons that gave the Muslims a great advantage, and their blacksmiths carefully guarded the secret to their manufacture. The secret eventually died out in the eighteenth century and no European smith was able to fully reproduce their method.

Two years ago, Marianne Reibold and colleagues from the University of Dresden uncovered the extraordinary secret of Damascus steel – carbon nanotubes. The smiths of old were inadvertently using nanotechnology.

Getting back to Day, he goes on to explain the Damascus/Valyrian steel connection to nuclear power (Note: Links have been removed),

Valyrian and Damascus steels were on my mind earlier this week when I attended a session at TechConnect World on the use of nanotechnology in the nuclear power industry.

Scott Anderson of Lockheed Martin gave the introductory talk. Before the Fukushima disaster, Anderson pointed out, the principal materials science challenge in the nuclear industry lay in extending the lifetime of fuel rods. Now the focus has shifted to accident-tolerant fuels and safer, more durable equipment.

Among the other speakers was MIT’s Ju Li, who described his group’s experiments with incorporating carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in aluminum to boost the metal’s resistance to radiation damage. In a reactor core, neutrons and other ionizing particles penetrate vessels, walls, and other structures, where they knock atoms off lattice sites. The cumulative effect of those displacements is to create voids and other defects that weaken the structures.

…

Li isn’t sure yet how the CNTs resist irradiation and toughen the aluminum, but at the end of his talk he recalled their appearance in another metal, steel.

In 2006 Peter Paufler of Dresden University of Technology and his collaborators used high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to examine the physical and chemical microstructure of a sample of Damascus steel from the 17th century.

The saber from which the sample was taken was forged in Isfahan, Persia, by the famed blacksmith Assad Ullah. As part of their experiment, Paufler and his colleagues washed the sample in hydrochloric acid to remove Fe3C particles. A second look with TEM revealed the presence of CNTs.

There’s still active interest in researching Damascus steel blades as not all the secrets behind the blade’s extraordinary qualities have been revealed yet. There is a March 13, 2014 posting here which describes a research project where Chinese researchers are attempting (using computational software) to uncover the reason for the blade’s unique patterns,

It seems that while researchers were able to answer some questions about the blade’s qualities, researchers in China believe they may have answered the question about the blade’s unique patterns, from a March 12, 2014 news release on EurekAlert,

Blacksmiths and metallurgists in the West have been puzzled for centuries as to how the unique patterns on the famous Damascus steel blades were formed. Different mechanisms for the formation of the patterns and many methods for making the swords have been suggested and attempted, but none has produced blades with patterns matching those of the Damascus swords in the museums. The debate over the mechanism of formation of the Damascus patterns is still ongoing today. Using modern metallurgical computational software (Thermo-Calc, Stockholm, Sweden), Professor Haiwen Luo of the Central Iron and Steel Research Institute in Beijing, together with his collaborator, have analyzed the relevant published data relevant to the Damascus blades, and present a new explanation that is different from other proposed mechanisms.

At the time the researchers were hoping to have someone donate a piece of genuine Damascus steel blade. From my March 13, 2014 posting,

Note from the authors: It would be much appreciated if anyone would like to donate a piece of genuine Damascus blade for our research.

Corresponding Author:

LUO Haiwen

Email: haiwenluo@126.com

Perhaps researchers will manage to solve the puzzle of how medieval craftsman were once able to create extraordinary steel blades.