A Jan. 24, 2014 news item on Nanowerk has a beautiful and timely (given the snowy, frigid weather in Eastern Canada and the US) opening for a story about crystals and metallic nanorods,

This time of year it’s not hard to imagine the world buried under a smooth blanket of snow. A picnic table on a flat lawn eventually vanishes as trillions of snowflakes collect around it, a crystalline sheet obscuring the normall – visible peaks and valleys of our summertime world.

This is basically how scientists understand the classical theory of crystalline growth. Height steps gradually disappear as atoms of a given material—be it snow or copper or aluminum—collect on a surface and then tumble down to lower heights to fill in the gaps. The only problem with this theory is that it totally falls apart when applied to extremely small situations—i.e., the nanoscale.

The Jan. 23, 2014 Northeastern University news release by Angela Herring, which originated the news item, goes on to provide some context and describe this work concerning nanorods,

Hanchen Huang, professor and chair of the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering [Northeastern University located in Massachusetts, US], has spent the last 10 years revising the classical theory of crystal growth that accounts for his observations of nanorod crystals. His work has garnered the continued support of the U.S, Department of Energy’s Basic Energy Science Core Program.

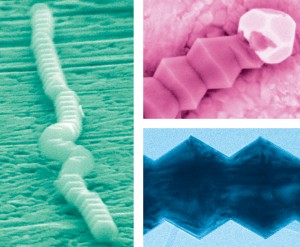

Nanorods are miniscule fibers grown perpendicular to a substrate, each one about 100,000 times thinner than a human hair. Surface steps, or the minor variations in the vertical landscape of that substrate, determine how the rods will grow.

“Even if some surface steps are closer and others more apart at the start, with time the classical theory predicts they become more equalized,” Huang said. “But we found that the classical theory missed a positive feedback mechanism.”

This mechanism, he explained, causes the steps to “cluster,” making it more difficult for atoms to fall from a higher step to a lower one. So, instead of filling in the height gaps of a variable surface, atoms in a nanorod crystal localize to the highest levels.

“The taller region gets taller,” Huang said. “It’s like, if you ever play basketball, you know the taller guys will get more rebounds.” That’s basically what happens with nanorod growth.

Huang’s theory, which was published in the journal Physical Review Letters this year, represents the first time anyone has provided a theoretical framework for understanding nanorod crystal growth. “Lots of money has been spent over the past decades on nanoscience and nanotechnology,” Huang said. “But we can only turn that into real-world applications if we understand the science.”

Indeed, his contribution to understanding the science allowed him and his colleagues to predict the smallest possible size for copper nanorods and then successfully synthesize them. Not only are they the smallest nanorods ever produced, but with Huang’s theory he can confidently say they are the smallest nanorods possible using physical vapor deposition.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Smallest Metallic Nanorods Using Physical Vapor Deposition by Xiaobin Niu, Stephen P. Stagon, Hanchen Huang, J. Kevin Baldwin, and Amit Misra. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110 (no. 13), 136102 (2013) [5 pages] DoI:

10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.136102

This paper is behind a paywall.

![The Endless Column, Târgu Jiu, România [downlaoded from http://terpconnect.umd.edu/~ckopetz/brancusi.htm]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/EndlessColumn-200x300.jpg)