Having supplied more than one tasty meal for mosquitos (or, as some prefer, mosquitoes), I am not their friend but couldn’t help but wonder about unintended consequences (as per Max Weber) on reading about a new patent awarded to Kansas State University (from a Nov. 12, 2014 news item on Nanowerk),

Kansas State University researchers have developed a patented method of keeping mosquitoes and other insect pests at bay.

U.S. Patent 8,841,272, “Double-Stranded RNA-Based Nanoparticles for Insect Gene Silencing,” was recently awarded to the Kansas State University Research Foundation, a nonprofit corporation responsible for managing technology transfer activities at the university. The patent covers microscopic, genetics-based technology that can help safely kill mosquitos and other insect pests.

A Nov. 12, 2014 Kansas State University news release, which originated the news item, provides more detail about the research,

Kun Yan Zhu, professor of entomology; Xin Zhang, research associate in the Division of Biology; and Jianzhen Zhang, visiting scientist from Shanxi University in China, developed the technology: nanoparticles comprised of a nontoxic, biodegradable polymer matrix and insect derived double-stranded ribonucleic acid, or dsRNA. Double-stranded RNA is a synthesized molecule that can trigger a biological process known as RNA interference, or RNAi, to destroy the genetic code of an insect in a specific DNA sequence.

The technology is expected to have great potential for safe and effective control of insect pests, Zhu said.

“For example, we can buy cockroach bait that contains a toxic substance to kill cockroaches. However, the bait could potentially harm whatever else ingests it,” Zhu said. “If we can incorporate dsRNA specifically targeting a cockroach gene in the bait rather than a toxic substance, the bait would not harm other organisms, such as pets, because the dsRNA is designed to specifically disable the function of the cockroach gene.”

Researchers developed the technology while looking at how to disable gene functions in mosquito larvae. After testing a series of unsuccessful genetic techniques, the team turned to a nanoparticle-based approach.

Once ingested, the nanoparticles act as a Trojan horse, releasing the loosely bound dsRNA into the insect gut. The dsRNA then triggers a genetic chain reaction that destroys specific messenger RNA, or mRNA, in the developing insects. Messenger RNA carries important genetic information.

In the studies on mosquito larvae, researchers designed dsRNA to target the mRNA encoding the enzymes that help mosquitoes produce chitin, the main component in the hard exoskeleton of insects, crustaceans and arachnids.

Researchers found that the developing mosquitoes produced less chitin. As a result, the mosquitoes were more prone to insecticides as they no longer had a sufficient amount of chitin for a normal functioning protective shell. If the production of chitin can be further reduced, the insects can be killed without using any toxic insecticides.

While mosquitos were the primary insect for which the nanoparticle-based method was developed, the technology can be applied to other insect pests, Zhu said.

“Our dsRNA molecules were designed based on specific gene sequences of the mosquito,” Zhu said. “You can design species-specific dsRNA for the same or different genes for other insect pests. When you make baits containing gene-specific nanoparticles, you may be able to kill the insects through the RNAi pathway. We see this having really broad applications for insect pest management.”

The patent is currently available to license through the Kansas State University Institute for Commercialization, which licenses the university’s intellectual property. The Institute for Commercialization can be contacted at 785-532-3900 and ic@k-state.edu.

Eight U.S. patents have been awarded to the Kansas State University Research Foundation in 2014 for inventions by Kansas State University researchers.

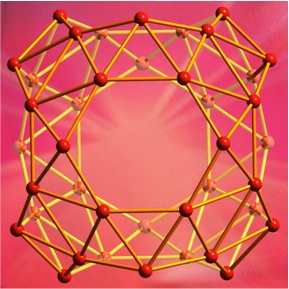

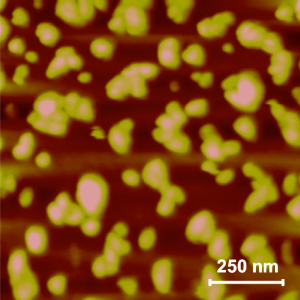

Here’s an image of the ‘Trojan horse’ nanoparticles,

The nanoparticles, pictured as gold colored, are less than 100 nanometers in diameter. photo credit: bogdog Dan via photopincc

My guess is that the photographer has added some colour such as the gold and the pink to enhance the image as otherwise this would be a symphony of grey tones.

So, if this material will lead to weakened chitin such that pesticides and insecticides are more effective, does this mean that something else in the food chain will suffer because it no longer has mosquitos and other pests to munch on?

One last note, usually my ‘mosquito’ pieces concern malaria and the most recent of those was a Sept. 4, 2014 posting about a possible malaria vaccine being developed at the University of Connecticut.